April 17

by Donna Farhi

Warrior Pose Two (Virabhadrasana II)

Benefits

Contraindications

By gracefully yielding to gravity, you can meet challenging poses with efficiency and ease.

Five minutes before beginning a class at a Yoga conference, a woman approaches me looking concerned. "I’m afraid," she says, "that I’m going to wrench my back in class."

I pause for a moment to reflect on the nature of the statement, then I respond in a calculated and shocked voice, "Do you mean you are willing to hurt yourself in this class today?"

When the question is met with a stare of incomprehension, I add, "The problem does not seem to be a physical difficulty; it seems to be how easily you relinquish your connection with what you know to be right for yourself." Slowly recognition dawns and her eyes soften.

In the course of this encounter, I realize how many ways this dilemma is posed—to the student who finds a new way to do a posture without pain, but clings to the old way because their

Benefits

Contraindications

By gracefully yielding to gravity, you can meet challenging poses with efficiency and ease.

Five minutes before beginning a class at a Yoga conference, a woman approaches me looking concerned. "I’m afraid," she says, "that I’m going to wrench my back in class."

I pause for a moment to reflect on the nature of the statement, then I respond in a calculated and shocked voice, "Do you mean you are willing to hurt yourself in this class today?"

When the question is met with a stare of incomprehension, I add, "The problem does not seem to be a physical difficulty; it seems to be how easily you relinquish your connection with what you know to be right for yourself." Slowly recognition dawns and her eyes soften.

In the course of this encounter, I realize how many ways this dilemma is posed—to the student who finds a new way to do a posture without pain, but clings to the old way because their belief in the ‘ideal’ form is greater than their belief in their own experience; to the person who injures herself over and over again in the name of her ‘practice’; to veteran students who are dependent on the authority of a teacher, system, or technique, and want someone to tell them what to do and exactly how to do it rather than discover it for themselves.

belief in the ‘ideal’ form is greater than their belief in their own experience; to the person who injures herself over and over again in the name of her ‘practice’; to veteran students who are dependent on the authority of a teacher, system, or technique, and want someone to tell them what to do and exactly how to do it rather than discover it for themselves.

In asana practice this tendency to disconnect from felt inner experience and to attend instead to outer reference systems plays itself out in myriad ways. The common pitfall is to make the accomplishment of an idealized form the primary imperative of asana practice, even when it means ignoring key warning signs that all is not well. What would our asana practice look like if we turned that inside out? What if the primary imperative of the practice, first, last, and always, was to find an inner alignment and attunement that allows our body to express its own innate integrity—right now, at this moment, in this body, rather than Swami Somebody Else’s body? What would happen if we made ourselves and our self-discovery more important than the pose? What new insights would we glean if we were willing to listen to subtle cues—to pause, adjust, or come out of a pose—regardless of what others thought of our actions?

When self-discovery is the primary imperative, inquiry leads, paradoxically yet inevitably, to impeccable form. On the other hand, starting with a set form into which we must puppeteer our way frequently leads to stilted, dysfunctional, and injurious ways of moving. And when there is only one way to do something, that one way tends to eliminate any possibility of an ongoing playful inquiry that would allow for the evolution of our practice as our body and our needs change. I find that students are amazingly adept at discovering alignment from the inside out when confidence in the self is restored and when they are guided by a self-positive intention. The key is to learn how to recognize the pattern of sensations that add up to a feeling of being ‘together’ within the form.

There are a few guidelines that can help us define what ‘feeling’ we are looking for, regardless of the posture and our level of experience. The first, and most important, is that the body should be able to breathe, and by breathe I mean that the subtle yet perceptible oscillation of the breath should be able to travel everywhere: in the floating spaces of the joints, throughout the soft center, along the undulating spine, and through the alternation of tone and release in the musculature. If you are not feeling a continual swelling and receding motion in a posture, prana is not able to circulate freely. Said another way: if the form of the posture impedes global respiration in the body, it’s poor form. It’s that simple.

Second, the structure of the posture should allow a strong and clear movement of force through the body. This can be tested—as you will see—just as we might test the stability of a chair before we sit on it. Force generally follows the line of the bones, and should be able to leap across the floating space of the joints, from limb to limb. As we consciously direct force through the body in asana, we want to be as efficient as possible so that this impulse sets up a chain reaction of force, catalyzing a powerful flow through the body. When you get a feel for finding the optimal place and position in asana, it’s like kicking a soccer ball in one swift action through a goalpost. Conversely, when the conditions are not optimal, we kick the ball here, we kick the ball there, in a disconnected series of actions that have no energetic continuity. This is especially true when we enter a posture from a series of discrete instructions, rather than finding the natural organic unfolding of the movement as a whole pattern.

Finally, when alignment of the body is good, stress is distributed throughout so that no one part tires before another. And when mastery is achieved, effort and release are balanced in such a way that we feel a neutral or translucent sensation of spaciousness throughout our whole being.

The posture I have chosen for this column, Warrior Pose Two (Virabhadrasana II), is commonly practiced with excessive strain on the hip, sacroiliac joints, and lumbar spine. The primary intellectual misconception about this posture is that the movement exists in only one plane; thus the all-too-common instruction ‘to imagine you are standing between two plates of glass’ or ‘in a narrow corridor’, the ideal being that both the left and right hip will be perfectly level with one another. Because so many of us find our way into asana by visual cues, it is understandable that many students struggle to perform this posture as if it were a two dimensional Egyptian hieroglyph.

Let’s walk our way through both the preparation and practice of this pose to see if we can find an alignment that makes sense to the body, and to see if we can reopen our feeling function to discover just how powerful the body can be when we make alignment an ‘inside’ job.

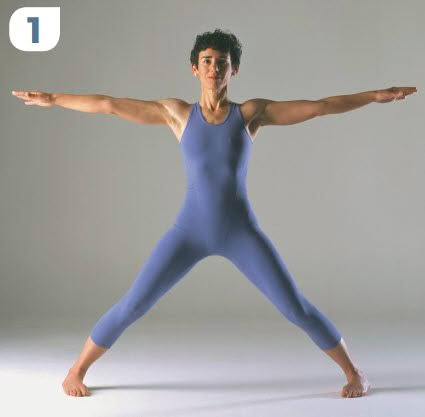

Preparation Stance 1

Stand with your feet hips-width apart. Extend your arms out to your sides level with your shoulders, and mentally drop a plumb line from your wrists to the floor. Now step your feet wide apart so that the outer edges of your feet are positioned approximately under your wrists. Everyone has different body proportions, so this distance is approximate. Turn your feet about 30˚ inward, which will allow your knees to align over your ankles and prevent your feet from slipping apart (Fig. 1).

Test your position by bending your knees to see if they track clearly over your feet. If they don’t, you probably need to turn your feet further inward. Experiment until you find just the right angle, one that affords you the best stability and balance.

Consciously focus on your exhalation. As you actively yield the weight of the legs into the ground, the trunk and spine will simultaneously ascend upward. Notice how your exhalation can have these same contrasting qualities: weighted and released, light and relaxed.

Preparation Stance 2

Turn your right foot out 90˚ by pivoting on your heel, spreading your toes, stretching the foot forward, and resting it lightly on the floor. Notice that as you rotate the foot outward the entire leg must rotate outward as well. To do this, the left side of your pelvis must move forward so that when you look down your left hip will be slightly in front of your right hip (Fig. 2). Notice how this small adjustment makes it easier to keep your entire right leg rotated outward over the right ankle and toes. Whenever you turn your feet in a particular direction the knees must obey the feet so that both the knee and foot are in

agreement about where they are going. The pelvis must revolve forward so that this relationship in the legs can be maintained.

Preparation Stance 2

Turn your right foot out 90˚ by pivoting on your heel, spreading your toes, stretching the foot forward, and resting it lightly on the floor. Notice that as you rotate the foot outward the entire leg must rotate outward as well. To do this, the left side of your pelvis must move forward so that when you look down your left hip will be slightly in front of your right hip (Fig. 2). Notice how this small adjustment makes it easier to keep your entire right leg rotated outward over the right ankle and toes. Whenever you turn your feet in a particular direction the knees must obey the feet so that both the knee and foot are in agreement about where they are going. The pelvis must revolve forward so that this relationship in the legs can be maintained.

Figure 3 illustrates a common mistake: the model has tried to keep her hips level, and thus she has forced her front knee to rotate inward. As a result, the head of her hip has fallen behind the line of the foot, setting up a weak zigzag line from foot to knee to hip to spine. The only way she can achieve this level position of the hips is by forcing the action through the sacroiliac joints (the joints between the sacrum and the two sides of the pelvis) and those of the lower back. Over time this common error can cause serious back, hip, and knee problems.

I have worked with many students with chronic and debilitating sacroiliac pain who have gained immediate relief by learning to let the movement be determined by the natural structure and function of the hip socket. Someone with a tight groin will

have to allow the pelvis to rotate further forward than a more flexible person, but no one can keep the two sides of the pelvis flush without putting excessive pressure through the sacroiliac and lumbar joints.

Figure 3 illustrates a common mistake: the model has tried to keep her hips level, and thus she has forced her front knee to rotate inward. As a result, the head of her hip has fallen behind the line of the foot, setting up a weak zigzag line from foot to knee to hip to spine. The only way she can achieve this level position of the hips is by forcing the action through the sacroiliac joints (the joints between the sacrum and the two sides of the pelvis) and those of the lower back. Over time this common error can cause serious back, hip, and knee problems.

I have worked with many students with chronic and debilitating sacroiliac pain who have gained immediate relief by learning to let the movement be determined by the natural structure and function of the hip socket. Someone with a tight groin will have to allow the pelvis to rotate further forward than a more flexible person, but no one can keep the two sides of the pelvis flush without putting excessive pressure through the sacroiliac and lumbar joints.

Your final check in this posture is to look down and see whether the heel of your right foot aligns with the arch or the inner heel of the back leg. Experiment to see which alignment offers you the greatest stability. You can use a floorboard or a line on the floor as a way to guide you the first time. Now you are ready to proceed.

The Sitting-Bone-to-Heel Connection

There is a powerful connection between the sitting bones of the pelvis (or more accurately, the center of the femur heads) and the heels. When you walk, run, or hop on one foot, your body is always trying to find the power line between your feet and the head of your femurs as a way to stay in balance and transmit the maximum force from the legs into the torso.

From Preparatory Stance 2, look at the heel of your right foot, and mentally draw a line from your heel along the floor underneath you to the other foot. Now bring your right sitting bone forward over this line. Once you bring your right sitting bone forward in line with the heel, you will no longer be able to see the floorboard underneath you when you look down.

Slowly bend your right knee, keeping the right sitting bone in line with your right heel. Did you find that you had to let your left hip come forward to do this? When you find this natural power line, your knee will align beautifully over the ankle (Fig. 4).

Now press horizontally back through your right foot (without straightening your leg), sending force from your right foot through your knee to the center of your hip. If your hip is aligned correctly the force will ‘jump’ across the bridge of your pelvis all the way into the other femur, down the leg, and into the left foot. You want to feel a clear and powerful force running from your front leg across your pelvis to your other leg, with no wobbles.

Take some time to experiment with how far forward your left hip needs to come to allow the right heel and sitting bone to line up. How does it feel when they do? There is no one correct position, for it will depend on your hip flexibility and the individual structure of your hip and pelvis.

Testing Your Alignment

There is an extremely accurate test of your alignment in this posture, but it should be done cautiously. Have your teacher or a practice buddy crouch facing your shin. From this angle they will be able to see whether the head of the femur is behind the line of the heel. They can help you by gently pressing behind the hip until the sitting bone lies plumb over that line (Fig. 5). Let the rest of your body organize itself around this adjustment.

Now, have your friend press directly back against the shin of the right leg, gradually increasing the steady pressure (Fig. 6). Do not press on the kneecap, or directly below the knee, and do not use jerky pressure. If the alignment between the legs and pelvis is clear and unimpeded, you’ll be able to take any amount of force generated by your friend. Then try moving your left hip back to be level with the right. Have your friend test again. Can you feel how this weakens and destabilizes the connection throughout the entire lower body?

Refinement

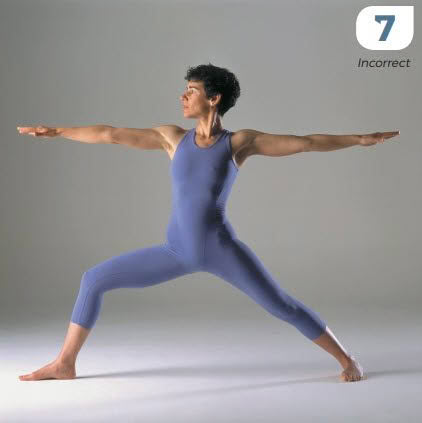

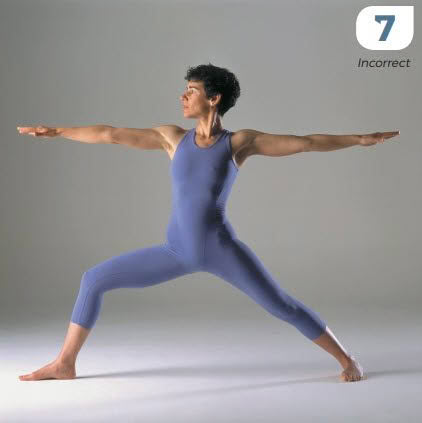

To create an even more powerful connection, check that your right knee is directly over your foot. If it is behind your foot, your stance is too wide (Fig. 7).

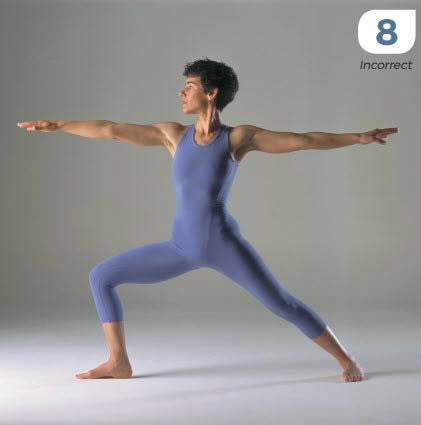

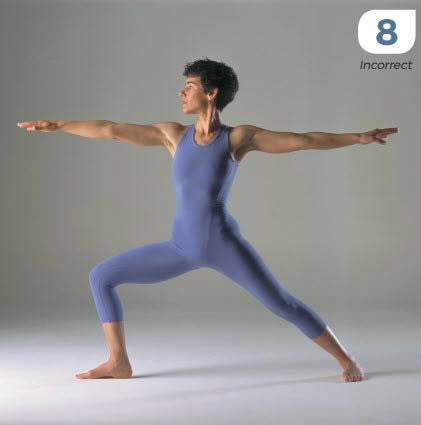

If it extends beyond your foot, your stance is too narrow (Fig. 8). When the shin is vertical

and the thigh parallel to the floor, your leg will form a stable tabletop position. Consciously lift through the pelvis and lower body so that the pelvis is buoyant on the femurs. This will open up the spaces in the hips even more and make for even greater transmission of force through the body.

Refinement

To create an even more powerful connection, check that your right knee is directly over your foot. If it is behind your foot, your stance is too wide (Fig. 7).

If it extends beyond your foot, your stance is too narrow (Fig. 8). When the shin is vertical and the thigh parallel to the floor, your leg will form a stable tabletop position. Consciously lift through the pelvis and lower body so that the pelvis is buoyant on the femurs. This will open up the spaces in the hips even more and make for even greater transmission of force through the body.

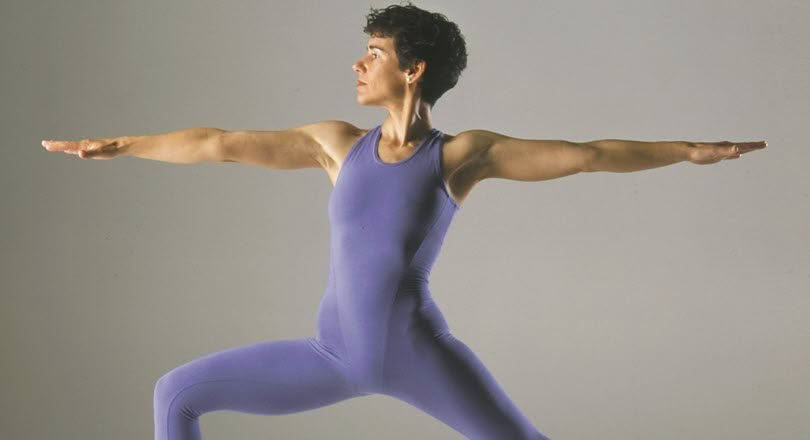

Begin to pay more attention to the diagonal line through your back leg. There should be a clear line of force from the hip through the knee to the foot (Fig. 9 final pose).

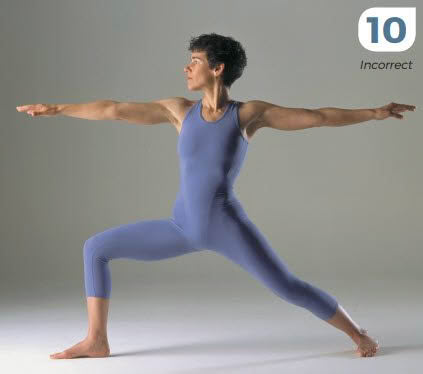

Because of the angle of the leg in relation to gravity, many people tend to drop through the back knee—which not only creates strain on the inner knee, but causes the whole of the lumbar spine to compress downward as well (Fig. 10)

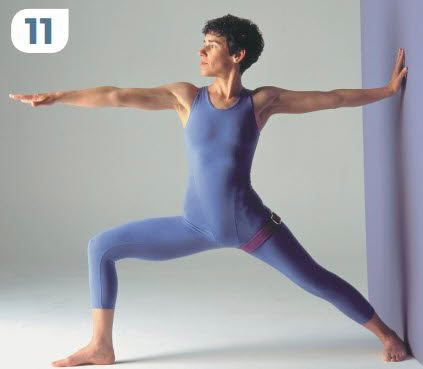

To create the right action, wedge your outer back foot against a wall for extra support and place a firm yoga tie or strap around the middle of the thigh and expand the thigh upward against the pressure of the strap (Fig. 11). Even more effective is to have a friend press downward on the top of the back thigh as you lift upward against their pressure.

To complete your practice of the posture, breathe deeply into the chest and arms, expanding the arms strongly out to the sides as you gaze over the right fingertips. Take 5–13 breaths before practicing the posture on the other side.

With all of these adjustments your aim is to create the clearest and most open pathways for force to travel through your body—and thus create the most efficient conduit for prana. As you breathe, imagine an uninterrupted energetic flow throughout your body. Consciously ‘shape’ your breath just as glassblowers shape their breath to create a form from the inside out. How can you make each joint space an open floodgate for the transmission of this flow? What subtle adjustments will allow you to feel the strong support of the skeleton while still allowing the muscles to stream along the bones, alternating the action of tone and release with that of the breath cycle? Notice how this open inquiry, regardless of how far you go physically, moves you closer and closer to experiencing yourself as whole.

Suggestions

Without forcing, experiment with extending the length of your exhalation, making it any amount longer than your inhalation. Explore the breath, allowing your body to move and release into the sensations of the breath as you move into and out of the posture. Keep the breath long and smooth.

This article originally appeared in Yoga International magazine, Issue 63, Dec/Jan. 2002

Photographs by Murray Irwin, Christchurch. © 2023 by Donna Farhi.

This article is from a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana and will be followed in the next post by an addendum: New Insights. There Donna shares what has changed, since the original article was published, after more than three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus article will be included. None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts