August 14

by Donna Farhi

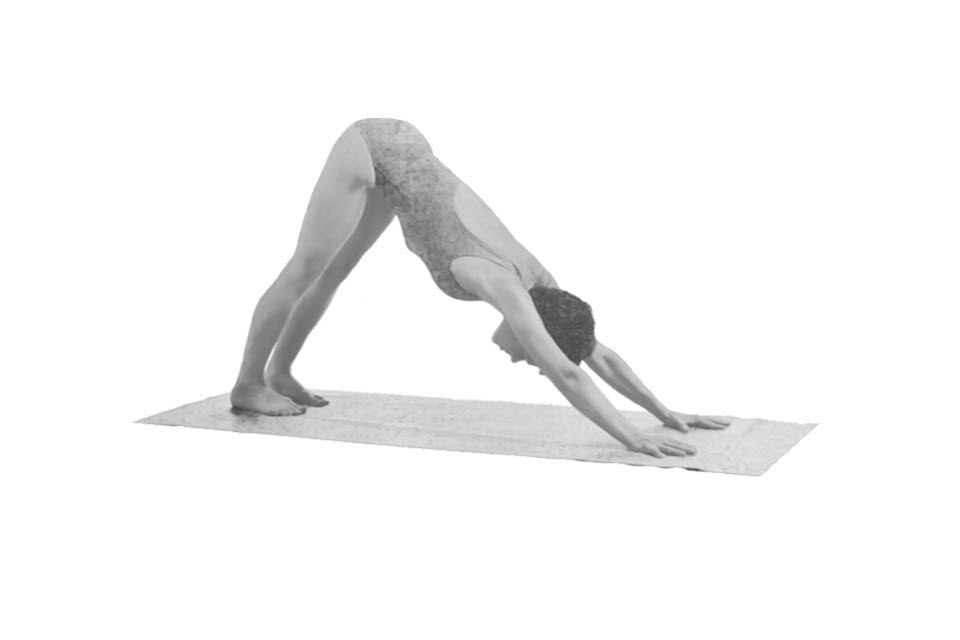

A panacea for whatever ails you, this popular pose combines the benefits of an inversion arm balance, forward bend, and restorative pose all rolled into one.

Benefits

Contraindications

Dear Reader

Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose) is an asana that no Yoga student ever outgrows. It’s the garlic of Yoga-a panacea for whatever ails you that combines the benefits of an inversion, arm balance, forward bend, and restorative pose all rolled into one. It opens the shoulders, strengthens the arms, lengthens and releases the spine, stretches the back of the legs, inverts the internal organs, and shifts the blood flow from the heart to the head. It can be used to invigorate or sedate you, depending on whether you practice it actively or passively with support.

As with many basic postures, a thorough understanding of Adho Mukha Svanasana serves as a building block for the practice of more complex movements. Trying to build a kinesthetic vocabulary in your Yoga practice without this pose would be like trying to compose a sentence without the letter e. Interestingly, this asana corresponds to one of the primary building blocks in human movement development, which acts as a platform for success in later, more sophisticated movement patterns.

One of a crawling infant’s first movements is to push its torso forward and backward using both arms and both legs. This fundamental quadruped action, called ‘homologous movement’, is exemplified by the symmetrical locomotion of a frog leaping. The ability to drive force through the body while on all fours underlies our capacity to do so in more complex patterns while standing. For example, whether a runner is the first across the finish line depends on how efficiently she can send force from the back to the front of the body with minimal deviation off the central axis.

The ability to propel force through the body in a clear line allows us to move through space efficiently and effortlessly. In Yoga we use these same forces not for locomotion, but to facilitate openness and the movement of energy currents within the body. By organizing and adjusting our physical structure, we can conduct energy through the soft tissue and soft organs in a sequential flow, as well as from bone to bone across the joint spaces. This smooth flow of energy is the hallmark of what we usually call ‘good alignment’.

Alignment is not a vague, esoteric concept, but a dynamic state that can be tested very easily and simply in almost any pose by having another person press strongly against us into the ideal line of force. If our alignment is poor and the line of force is broken, the assistant will see a ‘wobble’ in that part of the body. In Adho Mukha Svanasana the line of force runs from the center of the hands through the center of the elbows, through the center of the shoulders, through the front of the lumbar spine, and out through the sitting bones. Any break along this line diminishes one’s ability to move force efficiently.

Let’s look more closely at some of the common ways that students break this line of energy in Adho Mukha Svanasana. As you clarify your alignment, the pose will become lighter and longer, and no one part of the body will feel overtaxed.

Preliminary Practice

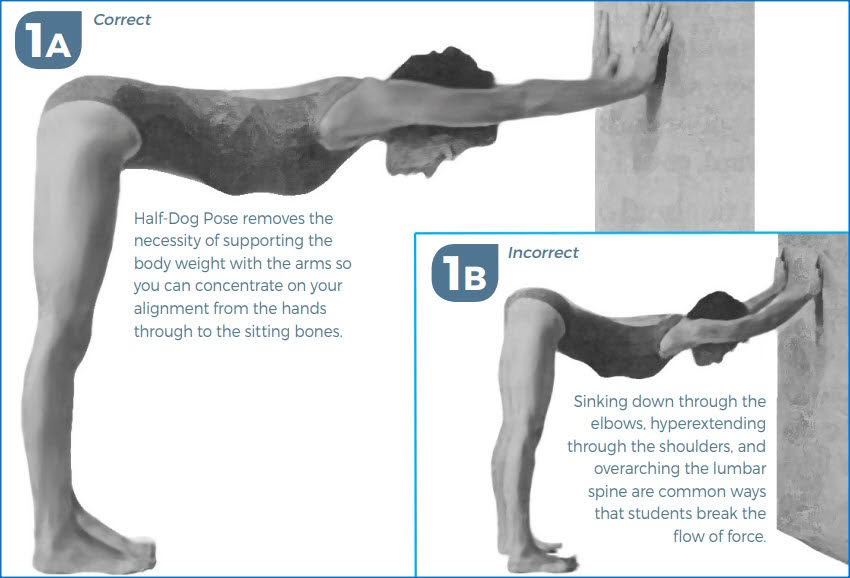

The common way to come up into Adho Mukha Svanasana is from the floor on all fours. If you are a beginner, however, carrying the full weight of the body through the arms may come as a bit of a shock. A simple variation called Half Dog Pose (Fig. 1A) removes some of that difficulty, allowing you to concentrate on your alignment.

Place your hands shoulder-width apart against a wall.

Spread your hands wide with the fingers pointing up and step the feet back until your torso is parallel with the floor. Make sure the feet are directly under the hips so the legs are perpendicular to the floor with the feet hip-width apart. Inhaling, press the wall away with your hands and, as you exhale, begin to reach back through the sitting bones. With each inhalation, see how firmly

you can press the hands into the wall. With each exhalation, lengthen the torso along a clear horizontal line.

To test your alignment, have an assistant stand behind you and press quickly (a gentle ‘shove’) on your sitting bones. If there are no breaks in your alignment, all you and your assistant will feel is the force coming through to your hands. However, if there is a break, your assistant will see a ‘wobble’ in that part of the body. If you do not have an assistant, stay in the posture for a minute or more and see where you tire first-this is often a good indication of where the line of force is broken.

In Adho Mukha Svanasana, the line of force commonly breaks at the wrists and elbows. Instead of forming a horizontalline, the wrists and forearms sag downward. This error is common in more flexible students (Fig. 1B: Incorrect).

Similarly, dropping the center of the shoulder joint below the level of the hands causes a break in the line of force. In this case, the front of the shoulder will overstretch while the posterior shoulder muscles contract. Tighter students may have the opposite problem, in which the shoulder lies above the line of the hands. Both positions impede the free flow of force from the arms into the torso. To correct their alignment, more flexible students should focus on lifting the shoulder blades up off the rib cage. Tighter students should focus on elongating the armpit so the shoulder joint begins to drop to the level of the arm bones.

The other common break in the line of force is in the spinal column. The spinal column has two primary curves the thoracic (upper back) and sacral (base of the spine), which are convex-and two secondary curvesthe cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back), which are concave. Any accentuation or reduction of these curves can alter the flow of force through the torso. (It is important to note that while the flow of force through the body should be straight, the outline of the body will be curved, with gradual transitions between each curve. Therefore, looking at the outline of the body can sometimes be deceptive.

If you find that your ‘wobble’ is in your lumbar spine, place your hand on the small of your back and feel whether the vertebrae are protruding or whether they are sinking away from the skin. If your lower back is rounded upward, try bending your knees slightly and rolling the sitting bones up until you can feel the vertebrae moving in. You might raise your hands higher up the wall to make it easier to bring the spine into a neutral position. If you tend to overarch your lumbar spine, adjust by lifting the base of the rib cage up and rolling the sitting bones slightly down toward the heels.

After you have made these adjustments, have your assistant check the flow of force again by steadily pressing on the sitting bones with her thumbs. See if you can reach back with your buttocks and press your sitting bones into her thumbs so all the spaces between the joints begin to open. After a few more moments, step one leg forward and come up out of the pose.

Beginner’s Practice

Coming up into Adho Mukha Svanasana is the same challenge you faced as a baby when you pushed your hands into the floor to raise your chest up off the floor. By recapitulating some of those early movements, you can begin to learn how to drive force through the body efficiently. Start on all fours with the hands shoulder-width apart and the knees slightly behind the hips. Begin to press back with your hands until your buttocks drop toward your heels. Let your back round as your head comes down toward the floor to open the shoulders (Fig. 2).

Then, with your toes turned under, push back through your feet until the buttocks come up and the chest moves forward slightly past the hands. Allow the spine to gently indent and the head to lift. Continue rocking forward and back, driving force from the periphery of the body (the hands and feet) through the center (the torso), gradually warming the hips, spine, and shoulders. After about 10 passes, as you press back from the hands, lift the knees off the floor and reach the sitting bones up and back, following the diagonal line of the arms.

In the beginning, you may want to try bending both arms and legs simultaneously and then slowly straightening them over the course of two or three breaths. Repeat this motion several times. This is a good way to work if your whole body is very tight, because the gentle oscillation between flexing and extending the limbs alternately releases and tones the muscles in a way that ‘holding’ a pose does not. When you come down, let yourself rest in Child’s Pose with the arms relaxed at your sides.

Advanced Practice

Even if you are a more advanced student coming into Adho Mukha Svanasana with bent arms and knees can be helpful, because it is easier to feel fluidity and openness in the joints when the limbs are flexed than when they are fully extended. Start from a fluid, relaxed position with elbows and knees slightly bent. Gradually begin to drive force sequentially from the hands all the way up to the coccyx so the limbs straighten over a few cycles of the breath.

Notice at what stage-and in what part of the body-you block the flow of force. Such blockages are frequently indicated by sensations of strain or tightness. Explore ways you can vary your position to release the tension. Feel free to move into positions that do not resemble the classical form of the pose if those variations free the blocked energy.

Working in this way allows you to create the openness and strength of the final position as you go. This approach is very different from immediately entering an incorrect position and then attempting to adjust it toward a more correct form. In the slower, more conscious style of working, the mind is actively engaged and involved in each stage of the movement. By contrast, in the more common, habitual way of working, we have no idea what happened between beginning the movement and arriving in the final position. We may have no awareness of how we came to be in Adho Mukha Svanasana with our shoulders hunched inward, our wrists collapsed, or our jaws locked.

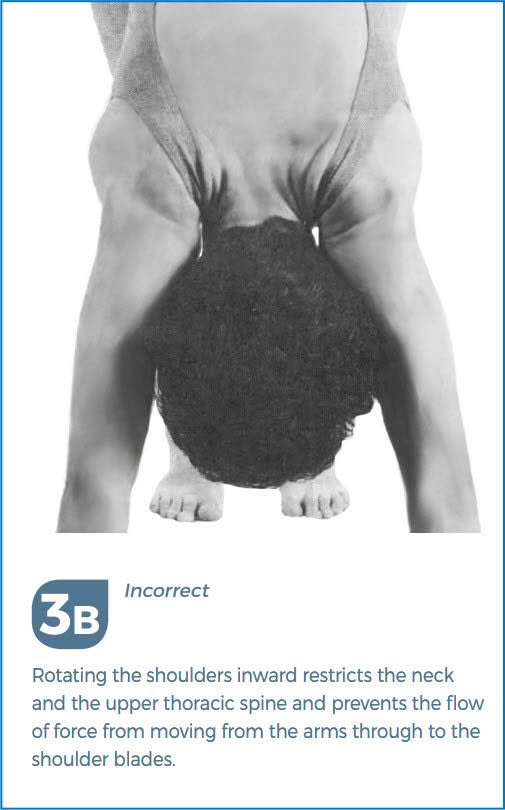

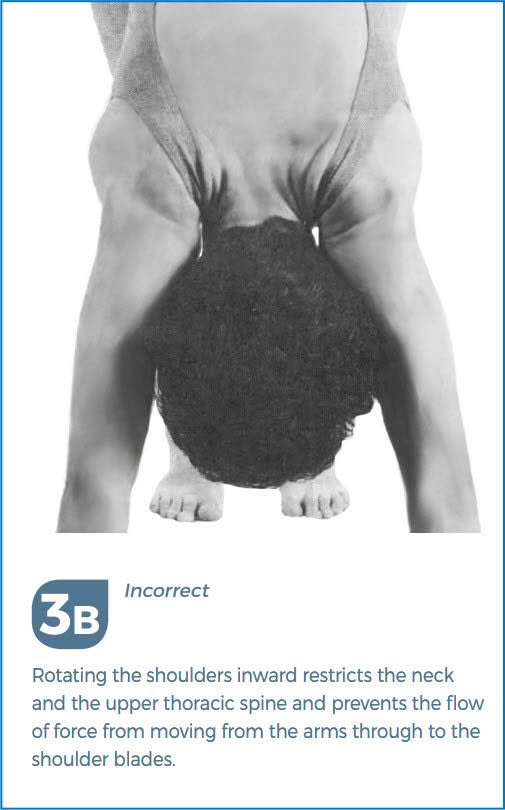

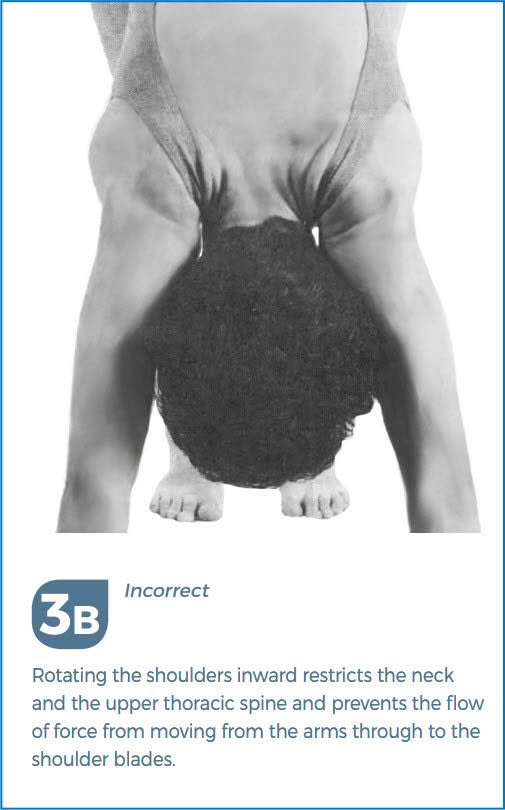

The most common block for all levels of students happens when the shoulders roll in instead of out (Fig. 3B: Incorrect). This problem is not surprising, considering that the architecture of the pose demands that the palms turn downward while the shoulders roll out-two movements that counter each other.

It’s hard to correct this error when the arms are already straight. Instead, bend both arms and begin to make ‘scooping’ motions with the elbows, turning the creases of the elbows up toward the sky and rolling the outer arms downward. Now very, very slowly begin to press into the palms as you allow the inner elbows to turn toward each other.

As you begin to straighten the arms, be vigilant not to contract the space between the neck and the outer shoulder. If the shoulders are released outward, the flesh will broaden from the neck out to the heads of the shoulders (Fig. 3A: Correct). In the beginning you will probably rock onto the outer edges of the hand to achieve the rotation. You can correct this tendency by pressing the base of the thumb and index finger down.

Advanced Practice

Even if you are a more advanced student coming into Adho Mukha Svanasana with bent arms and knees can be helpful, because it is easier to feel fluidity and openness in the joints when the limbs are flexed than when they are fully extended. Start from a fluid, relaxed position with elbows and knees slightly bent. Gradually begin to drive force sequentially from the hands all the way up to the coccyx so the limbs straighten over a few cycles of the breath.

Notice at what stage-and in what part of the body-you block the flow of force. Such blockages are frequently indicated by sensations of strain or tightness. Explore ways you can vary your position to release the tension. Feel free to move into positions that do not resemble the classical form of the pose if those variations free the blocked energy.

Working in this way allows you to create the openness and strength of the final position as you go. This approach is very different from immediately entering an incorrect position and then attempting to adjust it toward a more correct form. In the slower, more conscious style of working, the mind is actively engaged and involved in each stage of the movement. By contrast, in the more common, habitual way of working, we have no idea what happened between beginning the movement and arriving in the final position. We may have no awareness of how we came to be in Adho Mukha Svanasana with our shoulders hunched inward, our wrists collapsed, or our jaws locked.

The most common block for all levels of students happens when the shoulders roll in instead of out (Fig. 3B: Incorrect). This problem is not surprising, considering that the architecture of the pose demands that the palms turn downward while the shoulders roll out-two movements that counter each other.

It’s hard to correct this error when the arms are already straight. Instead, bend both arms and begin to make ‘scooping’ motions with the elbows, turning the creases of the elbows up toward the sky and rolling the outer arms downward. Now very, very slowly begin to press into the palms as you allow the inner elbows to turn toward each other.

As you begin to straighten the arms, be vigilant not to contract the space between the neck and the outer shoulder. If the shoulders are released outward, the flesh will broaden from the neck out to the heads of the shoulders (Fig. 3A: Correct). In the beginning you will probably rock onto the outer edges of the hand to achieve the rotation. You can correct this tendency by pressing the base of the thumb and index finger down.

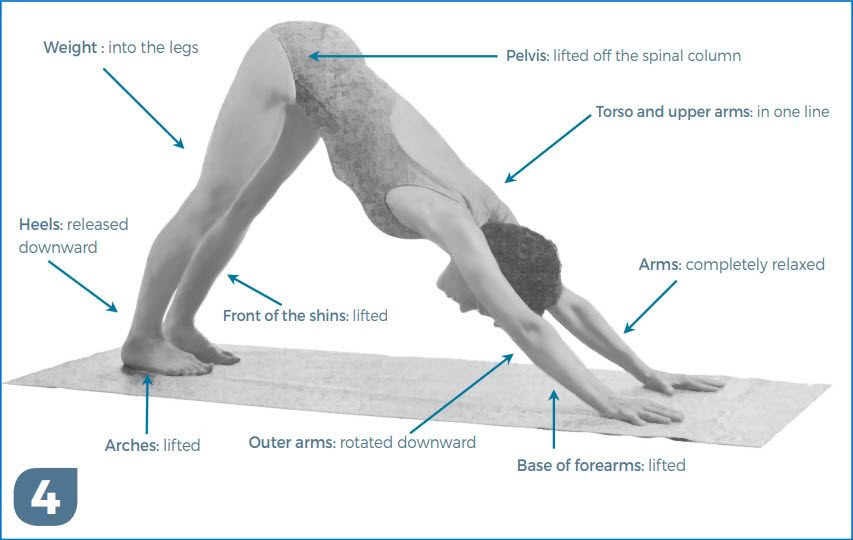

As you start to drive more and more force through the arms to lengthen the spinal column and bring the weight back onto the heels, you may tend to pull the neck and head back into the spine like a turtle retreating into its shell. Use your exhalation to help you release the breastbone away from the abdomen and to drop the upper thoracic vertebrae downward. Follow through by lengthening the neck and head in line with the rest of the spine (Fig. 4).

As the torso begins to lengthen, focus on drawing upward the space between the pubic bone and the tailbone. In more advanced students, continuing to extend the sitting bones upward after the basic pose has been established often causes a collapse between the lumbar and sacral spine and an overarching of those vertebrae. Instead, think of moving the perineum away from the crown of the head, thus keeping the spine in a more neutral position and maintaining the integrity of the joints.

Finally, check that the force moving through the joint spaces is not so strong as to impede the normal oscillatory movements of the breath as you stay in the posture. Hardening the muscles by driving too much force through the body will overwhelm the subtler current of the breath. Allow all the joints of the body (especially throughout the spinal column) to open and shift slightly with the inhalation and to settle and release with the exhalation.

As you open yourself to the dynamic wavelike motions of the breath, there is never any ‘final position’, but only an ongoing, open process of allowing life to move through you unimpeded. Having done the work of bringing the body into alignment, it is now time to give yourself over to the force that moves through you.

This article originally appeared in Yoga Journal magazine, Jan/Feb 1994. Photographs by Fred Stimpson. © 2023 by Donna Farhi.

It is part of a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana, each followed by New Insights gained from over three decades of teaching.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts