July 10

by Donna Farhi

Demanding complete concentration, this difficult balancing posture clears our mind and draws us

into the deeply pleasurable experience of ‘flow’.

Dear Reader

Please keep in mind that the images in this column were scanned from original archived articles and the quality might sometimes vary.

Benefits

Contraindications

Contrary to what we usually believe...the best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times—although such experiences can also be enjoyable, if we have worked hard to attain them. The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Optimal experience is thus something that we make happen.

-From Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

When teaching more advanced postures such as arm balances, I’m often presented with a question that I find very difficult to answer. “Why are we doing this?” The question comes in endless variations, but the central theme is always the same: Why bother to do something really difficult when we could have fun doing something easier?

Why should we challenge ourselves to do something hard when it takes so much energy and time? Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the author of Flow: The Psychology of

Why should we challenge ourselves to do something hard when it takes so much energy and time? Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the author of Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, has spent over two decades contemplating just such questions in a quest to understand what makes people happy. According to Csikszentmihalyi, the state that most people know as being ‘happy’ is the ‘flow’ state, in which we momentarily forget everything but the task on which we are focused in the present moment. In thousands of interviews and experiments, Csikszentmihalyi discovered that regardless of race, color, or age, the conditions for experiencing ‘flow’ are remarkably similar.

Why should we challenge ourselves to do something hard when it takes so much energy and time? Mihaly

Csikszentmihalyi, the author of Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, has spent over two decades contemplating just such questions in a quest to understand what makes people happy. According to Csikszentmihalyi, the state that most people know as being ‘happy’ is the ‘flow’ state, in which we momentarily forget everything but the task on which we are focused in the present moment. In thousands of interviews and experiments, Csikszentmihalyi discovered that regardless of race, color, or age, the conditions for experiencing ‘flow’ are remarkably similar.

Optimal Experience, has spent over two decades contemplating just such questions in a quest to understand what makes people happy. According to Csikszentmihalyi, the state that most people know as being ‘happy’ is the ‘flow’ state, in which we momentarily forget everything but the task on which we are focused in the present moment. In thousands of interviews and experiments, Csikszentmihalyi discovered that regardless of race, color, or age, the conditions for experiencing ‘flow’ are remarkably similar.

The most important element in entering the flow state, he says, is mastering the art of bringing order in consciousness. This ordering happens when we have a goal that we wish to achieve and a clear, resolute intention that magnetizes our attention on the task at hand. Entering the ‘flow’ state is highly enjoyable, which is why many people are driven to pursue difficult and even dangerous activities such as mountain climbing. In this state there is the perception, however fleeting, that we have control of our lives and are no longer held captive by external influences. In these moments, we’re no longer at the mercy of the natural tendency of the psyche towards entropy, or disorder, because the moment we focus our attention we bring about an inner ordering of experience. In this concentrated state, we forget ourselves; yet paradoxically, we also emerge from the experience with a strengthened sense of self.

While this technique for ‘flowing’ is simple in theory, it is exceedingly difficult in practice, as any Yoga student can attest who has tried and failed to practice alone at home. Because it is such a challenging pose, Adho Mukha Vrksasana (Downward Facing Tree, more commonly known as Handstand) offers many opportunities for us to enter into the flow state.

When practicing any Yoga posture, especially a difficult one, we need to have a clear intention or purpose. If we practice out of an egotistical desire to achieve some enviable state of perfection, or out of a masochistic impulse to whip the body into shape, neither the practice nor the ensuing rewards will bring us real growth or pleasure. If we understand that our purpose in doing Yoga is simply to practice and that it is not, as Csikszentmihalyi warns us, “…a battle against the self, but against the entropy that brings disorder to consciousness…” then we need search no further for a reason to step onto the mat. The practice itself is the reward because it provides us an opportunity to experience the inner ordering of experience that brings about flow.

If we practice out of an egotistical desire to achieve some enviable state of perfection, or out of a masochistic impulse to whip the body into shape, neither the practice nor the ensuing rewards will bring us real growth or pleasure.

Preliminary Practice

Handstand is basically an upside-down Tadasana (Mountain Pose), in which the arms rather than the legs support the body. Just as the downward pressure of the feet in Tadasana generates force that rebounds up through the legs and torso, now the hands and arms must generate force that rebounds up through the body like a fountain. The force moving through the body acts as a dynamic support to keep the body in one line.

Getting up into Handstand, aligning the body, and balancing without support involve integrating the movements of the abdominal muscles (especially the deep psoas muscles that connect the torso to the legs), the sacrum and pelvis, and the thighs. When these structures are moving in a harmonious relationship with one another, strength is a functional rather than a structural phenomenon. That is, strength is created by the integration and alignment of body structures rather than the actual strength of any individual muscle or limb. Thus, the real difficulty in Handstand is not, as is commonly thought, developing enough strength in the muscles; sufficient strength can actually be developed with little awareness. The real challenge lies in cultivating the complex patterning of the neuromuscular system necessary to achieve an integration of many movements simultaneously.

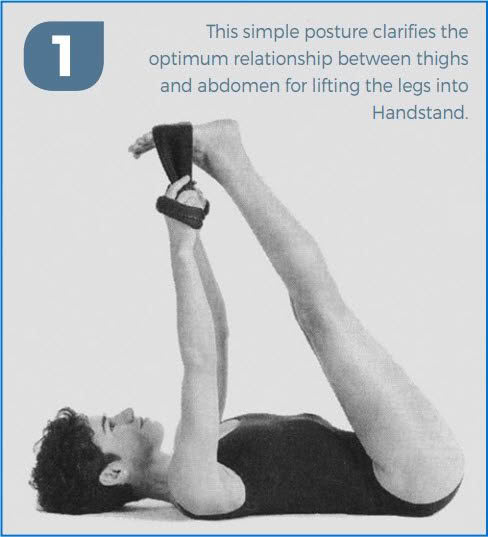

In Handstand, the relationship between the abdomen and the legs is central. To experience this relationship, lie on your back with the legs bent (Fig. 1). Put a tie around the soles of your feet and extend your legs up toward the ceiling so the thighs form a 90° angle (or less) with the abdomen. If your hamstrings are tight, you may have to bend the knees slightly to bring the thighs into this position. As the thighs move closer to the chest, the heads of the femur bones will descend away from the shoulders. The abdominal muscles will then fold back toward the spine, where they are in an excellent position for lifting the weight of the legs. At the same time, the spine lengthens, supported by the abdominal muscles.

In Handstand, the relationship between the abdomen and the legs is central. To experience this relationship, lie on your back with the legs bent (Fig. 1). Put a tie around the soles of your feet and extend your legs up toward the ceiling so the thighs form a 90° angle (or less) with the abdomen. If your hamstrings are tight, you may have to bend the knees slightly to bring the thighs into this position. As the thighs move closer to the chest, the heads of the femur bones will descend away from the shoulders. The abdominal muscles will then fold back toward

Now let the legs move away from the abdomen until they are at a 45° angle to the floor. Notice how the abdomen bulges outwards and the lower back arches away from the floor. In this position, the abdominal muscles are in a very poor position to lift the weight of the legs. To come up into Handstand with minimal effort, it is necessary to bring the thighs into at least a 90° angle

with the abdomen. In this position, the pelvis becomes the fulcrum for the movement, and you can lift the legs with minimal effort.

muscles will then fold back toward the spine, where they are in an excellent position for lifting the weight of the legs. At the same time, the spine lengthens, supported by the abdominal muscles.

Now let the legs move away from the abdomen until they are at a 45° angle to the floor. Notice how the abdomen bulges outwards and the lower back arches away from the floor. In this position, the abdominal muscles are in a very poor position to lift the weight of the legs. To come up into Handstand with minimal effort, it is necessary to bring the thighs into at least a 90° angle with the abdomen. In this position, the pelvis becomes the fulcrum for the movement, and you can lift the legs with minimal effort.

Now let the legs move away from the abdomen until they are at a 45° angle to the floor. Notice how the abdomen bulges outwards and the lower back arches away from the floor. In this position, the abdominal muscles are in a very poor position to lift the weight of the legs. To come up into Handstand with minimal effort, it is necessary to bring the thighs into at least a 90° angle with the abdomen. In this position, the pelvis becomes the fulcrum for the movement, and you can lift the legs with minimal effort.

Beginning Practice

A student is usually physically ready to do Handstand when he or she can comfortably practice Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog) for one to two minutes with the arms and torso in one line. The student should also be able to carry the weight of the body in Chaturanga Dandasana (Four-Limbed Stick Pose) and in Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (Upward Facing Dog) without resting the legs on the floor. The ability to perform these poses is a good indication that the wrists are strong enough to take the considerable stress of Handstand. (Keep in mind that these objective yardsticks may mean little if you are mortally terrified of the very idea of turning upside down!)

If you are attempting Handstand for the first time, it may be helpful to work with a teacher or friend who can ‘spot’ you as you kick up. Work with a wall behind you. You may want to put a pillow or folded blanket on the floor between your hands (but never behind your feet, where you may slip on it) to cushion any potential fall. You can also stack enough bolsters or blankets between your hands so the top of the head lightly touches them without collapsing into their support.

To prepare to enter Handstand, take Downward Facing Dog Pose with the hands a shin’s distance (12 -18 inches) from the wall. Spread the fingers of your hands wide apart to distribute the stress of the body’s weight evenly through the bones of the hand and wrist. To prevent strain in the wrists, check that the inner wrist is pressing as firmly against the floor as the outer wrist. If your wrists are very stiff, you may wish to place a folded nonslip mat under the base of the wrist to reduce the extension at the joint. Make sure that the angle between your thighs and your abdomen is 90° or less, as it was when you were lying on the ground.

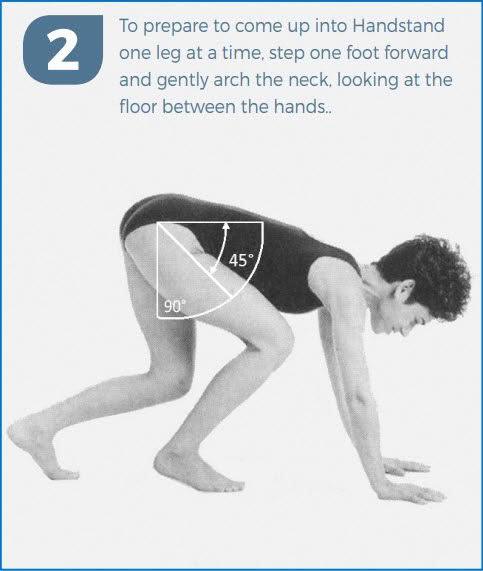

Now reach back through the sitting bones so the shoulder joints open fully. Step one foot forward until it is midway between the hands and feet. Gently arch the neck, looking at the floor just in front of the hands. Bend both knees, lowering the buttocks toward the heels as if you were going to do a sprint start (Fig. 2). Then spring, extending your legs as they come off the floor to touch the wall. If you keep the knees and ankles fully relaxed, the legs can act like coiled springs which, when released, create enough momentum to lift the body over the arms. If you find that you can’t get up or that you come down with a thump, you are probably bracing the ankle and knee joints out of fear. To get enough momentum, let the torso and legs swing freely like a pendulum. Practice bouncing up and down just a few inches off the floor from the crouched sprint position, letting the ankles and knees gently fold as the foot makes contact with the floor.

Many beginners have difficulty getting up because they try to bring their feet to the wall without first bringing the pelvis over the chest. This action results in a kind of whiplash on the lower back, in which the torso stays in the Dog Pose position while the legs

Now reach back through the sitting bones so the shoulder joints open fully. Step one foot forward until it is midway between the hands and feet. Gently arch the neck, looking at the floor just in front of the hands. Bend both knees, lowering the buttocks toward the heels as if you were going to do a sprint start (Fig. 2). Then spring, extending your legs as they come off the floor to touch the wall. If you keep the knees and ankles fully relaxed, the legs can act like coiled springs which, when released, create enough momentum to lift the body over the arms. If you find that you can’t get up or that you come down with a thump,

you are probably bracing the ankle and knee joints out of fear. To get enough momentum, let the torso and legs swing freely like a pendulum. Practice bouncing up and down just a few inches off the floor from the crouched sprint position, letting the ankles and knees gently fold as the foot makes contact with the floor.

thrust forcefully backwards. I have seen quite advanced students practice this bad habit. Instead, fix your eyes on a point just beyond your head and focus on bringing your buttocks over that point; the legs will naturally extend a moment later.

Many beginners have difficulty getting up because they try to bring their feet to the wall without first bringing the pelvis over the chest. This action results in a kind of whiplash on the lower back, in which the torso stays in the Dog Pose position while the legs thrust forcefully backwards. I have seen quite advanced students practice this bad habit. Instead, fix your eyes on a point just beyond your head and focus on bringing your buttocks over that point; the legs will naturally extend a moment later.

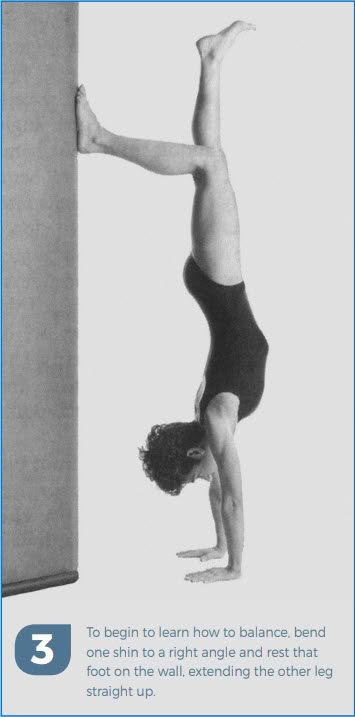

Once your feet are lightly resting against the wall, bend one knee so the lower leg forms a right angle to the thigh and torso (Fig. 3). Extend the other leg straight up in line with the body. Bending one leg will make it easier to bring the pelvis into an upright position. Contract the muscles at the base of the buttocks and thigh to draw the sitting bones toward the backs of the knees. This action will prevent the pelvis and legs from falling backward. Simultaneously, draw the pubic bone toward the navel so that the abdominal muscles are activated to hold the pelvis steady. When you feel you have found a position of balance, lightly extend the bent leg until it touches the other leg.

At first, this balanced position will feel impossible to sustain. The key to balance is maintaining a neutral position of the pelvis relative to the legs. Keep lifting through the back of the pelvis, with your eyes focused on a spot just beyond your fingertips. Even just a few seconds of balance will teach volumes to your neuromuscular system.

From the very beginning, be careful not to get into the habit of entering Handstand by forcefully hitting the wall with both feet and then sustaining the pose by leaning your weight against the wall. If you practice the pose this way, you may become permanently married to the wall. When you leap with too much force and slam into the wall, you teach the body that the wall is what stops you from tumbling over, rather than your muscle coordination. When you try to balance in the center of the room,

At first, this balanced position will feel impossible to sustain. The key to balance is maintaining a neutral position of the pelvis relative to the legs. Keep lifting through the back of the pelvis, with your eyes focused on a spot just beyond your fingertips. Even just a few seconds of balance will teach volumes to your neuromuscular system.

you will be rudely awakened to this deception! When you lean against the wall, you relax the muscles in the front of the thigh and the abdomen, thereby letting go of the very muscles you will need to activate to find your balance later. Moreover, it’s very difficult to bring the pelvis into a neutral position when both legs are extended backwards to touch the wall, because the abdominal muscles are in a poor position to contract.

From the very beginning, be careful not to get into the habit of entering Handstand by forcefully hitting the wall with both feet and then sustaining the pose by leaning your weight against the wall. If you practice the pose this way, you may become permanently married to the wall. When you leap with too much force and slam into the wall, you teach the body that the wall is what stops you from tumbling over, rather than your muscle coordination. When you try to balance in the center of the room, you will be rudely awakened to this deception! When you lean against the wall, you relax the muscles in the front of the thigh and the abdomen, thereby letting go of the very muscles you will need to activate to find your balance later. Moreover, it’s very difficult to bring the pelvis into a neutral position when both legs are extended backwards to touch the wall, because the abdominal muscles are in a poor position to contract.

At first, this balanced position will feel impossible to sustain. The key to balance is maintaining a neutral position of the pelvis relative to the legs. Keep lifting through the back of the pelvis, with your eyes focused on a spot just beyond your fingertips. Even just a few seconds of balance will teach volumes to your neuromuscular system.

From the very beginning, be careful not to get into the habit of entering Handstand by forcefully hitting the wall with both feet and then sustaining the pose by leaning your weight against the wall. If you practice the pose this way, you may become permanently married to the wall. When you leap with too much force and slam into the wall, you teach the body that the wall is what stops you from tumbling over, rather than your muscle coordination. When you try to balance in the center of the room, you will be rudely awakened to this deception! When you lean against the wall, you relax the muscles in the front of the thigh and the abdomen, thereby letting go of the very muscles you will need to activate to find your balance later. Moreover, it’s very difficult to bring the pelvis into a neutral position when both legs are extended backwards to touch the wall, because the abdominal muscles are in a poor position to contract.

Remember, the more force you use to spring into the pose, the greater the momentum you will have to stop in order to balance. Each time you practice, try using less force, until you can touch the wall silently. The next step will be to pretend that the wall isn’t there and try to go directly to the balanced position.

The real difficulty in Handstand lies not in developing enough strength in the muscles, but in cultivating the complex patterning of the neuromuscular system necessary to achieve an integration of many movements simultaneously.

Advanced Practice

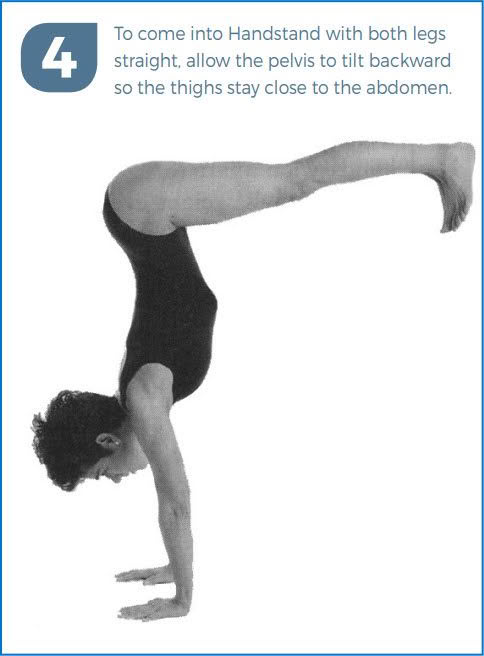

Once you have mastered coming into Handstand one leg at a time at the wall and can balance near the wall with good alignment, you’re ready to attempt coming up with both legs together. Begin in Downward-Facing Dog, as you did for the beginner’s version. This time, walk both feet forward toward the hands until the bent knees touch the rib cage. Bend the knees, lower the buttocks toward the heels, and spring up with both legs together, keeping the knees bent. Concentrate on keeping the thighs very close to the chest and the heels close to the sitting bones. Practice this stage until you can stop yourself with the pelvis balanced over the chest and the head and the legs still bent. Then, from this balanced position, extend both legs overhead.

Lifting into the pose with both legs straight is almost exactly the same as the bent-leg variation, with a few key exceptions. This approach will require greater strength in the upper body and abdominal muscles because the legs are farther away from your center of gravity. But controlling the final balance will be easier.

Prepare as you did for the bent-leg variation, except this time walk the feet even closer to your hands and raise the creases of your hips high so the pelvis is elevated over the chest. Now bend the knees, bringing the buttocks close to the heels. As you spring, keep the thighs very close to the belly and allow the sacrum and pelvis to tilt backward (Fig. 4).

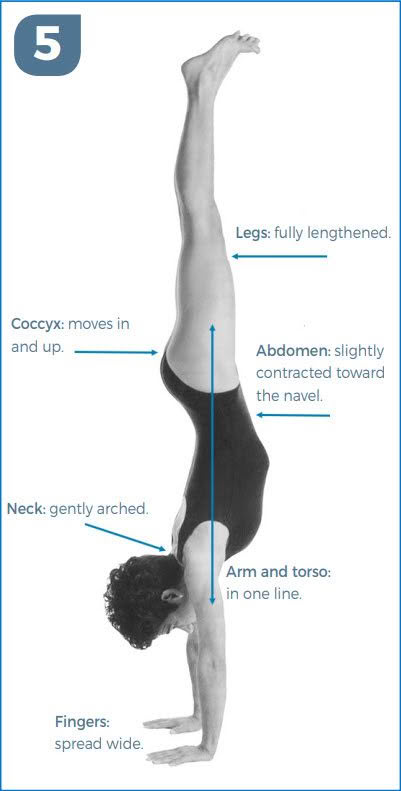

As soon as the feet leave the ground, immediately straighten the legs and slowly bring them to vertical extension over the torso (Fig. 5). Once you feel that your balance is steady, begin to extend fully through the arms, pressing the floor away with your hands and reaching strongly up through the heels. You might have a teacher or assistant press on the bottoms of your feet so you have some real resistance to work against.

A common error for both beginning and advanced students is to balance on the joints by hyperextending the spine into a banana shape. This posture does make it easier to balance because it creates a wider base of support over which the legs can roam. However, it is tremendously stressful to the lower back. Instead, fully elongate through the shoulder, spine, and hip joints, bringing the body into a straight line and opening the space between the bones. The balance will be lighter but more precarious because the force moving up through the body from the arms to the feet must travel across the open space in the joints rather than from bone to bone. With the spinal curve no longer exaggerated into a banana shape, the center of gravity has narrowed and you have less room for error. As you refine the alignment, the posture will begin to feel light and effortless.

Once you can confidently balance with the wall behind you, it is time for a trial separation from the wall. Have a teacher or trusted partner stand directly behind you (never to your side) so they can effectively stop you from falling, if necessary. Most of your practice in the center of the room will be focused on learning to gauge how much force is required to get up and how much control is necessary to stop that initial momentum.

Balancing in the center of the room is an exhilarating act, bringing both lightness and focus to the mind. But remember, the goal of balancing is not the most important aspect of practicing the pose. Enjoy the practice each step of the way. Within each successive challenge lies the key to bringing ourselves fully into the moment.

This article originally appeared in Yoga Journal magazine, Jan/Feb 1993. Photographs by Fred Stimson. © 2023 by Donna Farhi.

This is one article from a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana and will be followed in the next post by an addendum: New Insights. There Donna will share what has changed, since the original article was published for her from more than three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus article will be included. None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts