May 15

by Donna Farhi

Support the muscular effort of your backbends by engaging your inner body.

Support the muscular effort of your backbends by engaging your inner body.

If you’re like most Yoga students, you usually move into your asanas by focusing on muscles and bones. But to produce truly balanced movement, all your body’s systems must work in concert—not just the muscular and skeletal systems, but also many others, including your circulatory system, your respiratory system, and the soft inner body of your digestive tract. Because we tend to repeat what we know best, we have systems in our bodies we don’t visit very often. As long as these systems remain undeveloped, we lack our full range of expression, both physically and emotionally.

Benefits

Contraindications

Dear Reader,

Let’s explore what can happen to the quality of your movement in a simple backbend, Locust Pose (Salabhasana), when you bring an awareness of the soft inner body of your digestive tract into the foreground. Cultivating this awareness can give you a more complete picture of who you really are, and thus allow you to experience and act from your body in new ways.

How can you become aware of your inner body? Let’s begin by reviewing one of the ways babies develop awareness of themselves and their world. The earliest human developmental movement patterns, which lay the groundwork for our somatic life, primarily focus on the inner body. When we search for and nurse from our mother’s breast, we engage the mouth and the suckling reflex. As we suck and swallow, we tone the soft palate, the pharynx, and the entire digestive tract. We begin to orient our body around this soft vertical axis that later serves as crucial support for the movements of our bony spinal column. These ‘mouthing’ movements help us connect with and satisfy a core aspect of being—our basic need for nourishment and give us our first tool for engaging the world.

As we grow older, we become much more skillful in using our bones and muscles to manipulate the outer world. Our focus shifts away from our internal processes and toward relating to others and to our environment. In America, perhaps in part because we live in a culture obsessed with external appearances, adults often function almost exclusively with this external focus. When we practice asanas, we tend to make our bodies conform to an image rather than using an internal focus to feel for harmony in the body. In a more

As we grow older, we become much more skillful in using our bones and muscles to manipulate the outer world. Our focus shifts away from our internal processes and toward relating to

As we grow older, we become much more skillful in using our bones and muscles to manipulate the outer world. Our focus shifts away from our internal processes and toward relating to others and to our environment. In America, perhaps in part because we live in a culture obsessed with external appearances, adults often function almost exclusively with this external focus. When we practice asanas, we tend to make our bodies conform to an image rather than using an internal focus to feel for harmony in the body. In a more balanced approach, the inner focus so dominant in infancy would continue to serve as a supportive reference point for all outward activity.

balanced approach, the inner focus so dominant in infancy would continue to serve as a supportive reference point for all outward activity.

others and to our environment. In America, perhaps in part because we live in a culture obsessed with external appearances, adults often function almost exclusively with this external focus. When we practice asanas, we tend to make our bodies conform to an image rather than using an internal focus to feel for harmony in the body. In a more balanced approach, the inner focus so dominant in infancy would continue to serve as a supportive reference point for all outward activity.

To help recover your inner awareness, you can return to some of the movements you made as an infant. Before you begin, wash your hands thoroughly. Lie on your belly on a soft surface, placing a clean cloth under your face. Then close your eyes and connect with your breathing. Slowly let your attention shift to your mouth, imagining that this is the only medium you have for exploring the world. Letting your focus shift from your hard vertebral body to your soft visceral body, explore the inside of your mouth with your tongue.

Brush the ground with your mouth: Explore the textures around you, tasting and sucking your fingers and thumbs. As you swallow and suck, feel how the drawing action of the mouth continues through the entire digestive tract, toning all the internal organs which lie parallel to your spinal column.

If you hold an infant while she is feeding, you can feel a wonderful undulating movement throughout the entire length of her body. Feel for this same movement in your own visceral body, following down from your mouth through your esophagus, down into your stomach, into your small intestine, through your large intestine and completing the journey at the anus.

Consider the pathway of the digestive tract as the ‘inner skin’ of your body; a skin that is in contact with everything you take into your mouth. Also allow yourself to explore with your anus, as young children do, reaching and drawing back, feeling how this movement counterbalances the actions of your mouth.

Now begin to explore what it’s like to initiate larger movements from an awareness of your soft inner body. Notice, as you begin movement from your mouth and digestive tract, that your back muscles no longer have to carry the full burden when lifting your body away from the ground. (A helpful image for finding this way of moving is to imagine yourself as a tiny inchworm, drawing your front body up into your back body to lift yourself along the ground.) Try moving with and without this internal support to discover the relationship between your digestive tract and your spine.

Connecting With Your Core

It’s not uncommon to feel a little silly or embarrassed while exploring like this. You may even have feelings of shame, anger, or sadness as you connect with your need for nourishment and your desire for pleasure. Mouthing is a stage of development characterized by strong feelings of need and desire, and as you revisit this stage of your personal evolution, you may find yourself remembering whether these needs were met adequately in your childhood.

Consciously exploring the mouthing pattern as an adult not only gives you an opportunity to rebalance your physical body, it also gives you an opportunity to rebalance your emotional anatomy. When the mouthing pattern offers its underlying support, you can feel a connection between your head, neck, and trunk as well as a balanced use of the spine throughout your entire torso. But you may also experience a concomitant psychological and emotional balance that expresses itself as a stronger sense of personal center and increased abilities to feel pleasure, to seek appropriate nourishment from others, and to nourish yourself from within.

Engaging Your Inner Body

Salabhasana is an excellent asana for learning to move from your inner body. These Salabhasana variations progress from those that are the least stressful on the back to those that are more taxing; from versions where the arms and legs are closer to the torso to versions where they are farther away. When you lift a heavy object you hold it close to your body to reduce strain on your back. In Salabhasana, the arms and legs represent the external weights: the farther they stretch away from the body, the greater the potential strain on the lumbar spine. If you progress slowly, your back will gradually strengthen so that it can easily manage this extra weight.

Starfish Salabhasana

If you tend to feel compression in your lower back when you do backbends, use a folded blanket under your pelvis for these Salabhasana variations. Your hips should be on the back edge of the blanket, but not your thighs. This will help to decrease the angle of your lumbar curve, protecting your back. Some people find using two blankets gives them even greater ease.

To begin gently exploring the pose, lie on your belly, spreading your arms and legs wide apart so that your body forms a starfish shape. Imagine your limbs (head, tail, arms, and legs) as fluid projections from your navel center.

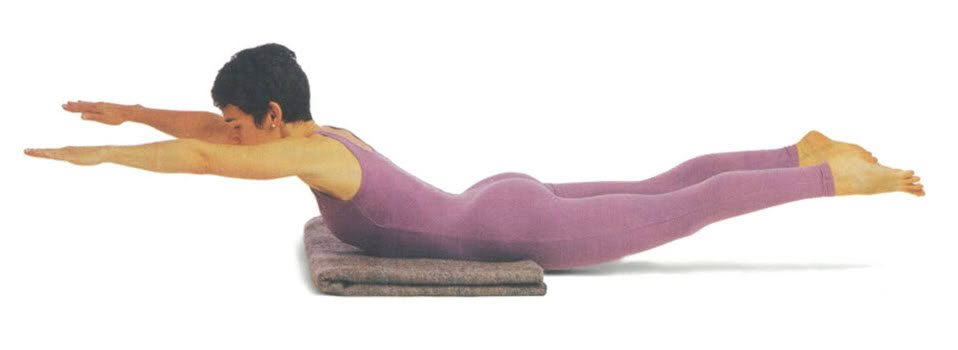

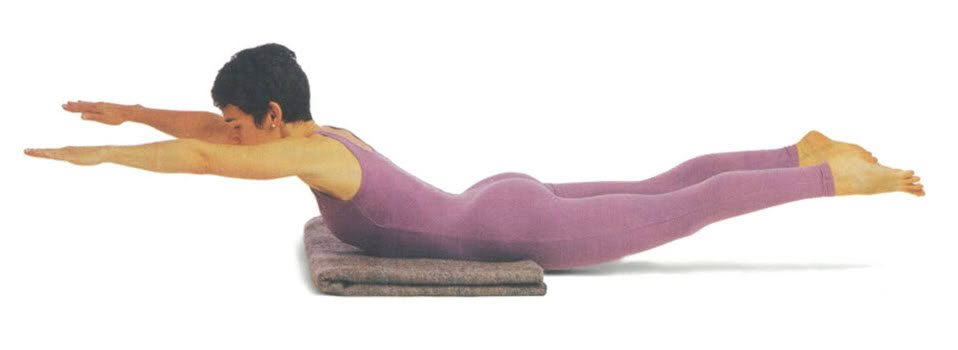

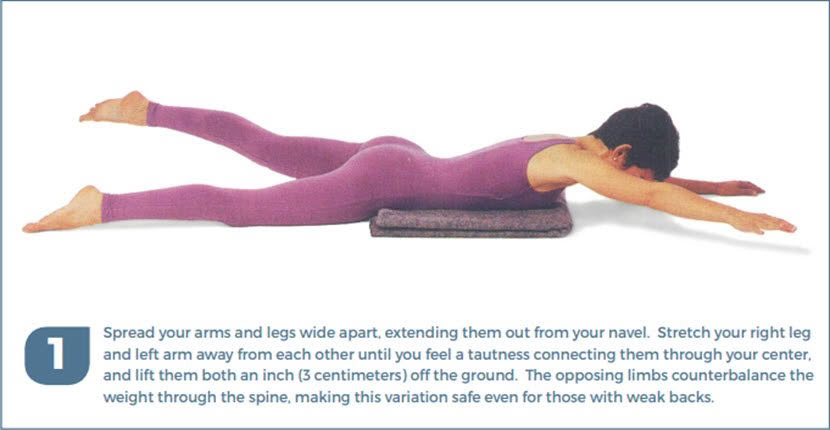

Begin by slightly lifting and extending your legs away from your belly, creating space along both sides of your waist. Settle the legs back into the ground and then stretch the right leg and left arm away from one another, without raising them off the floor. (Even though you’re extending your limbs, this is an especially gentle variation, useful for people with weak backs; using diagonally opposed limbs counterbalances the weight through the spine.) When you feel a tautness connecting your opposing limbs through your center, slowly raise the limbs an inch (two centimeters) off the floor (Fig. 1). Also allow your head, neck, and chest to come up slightly. Keep your gaze low.

Don’t try to raise yourself higher at this stage, but focus instead on opening the limbs away from your center. In this way you will be strengthening your back muscles in a lengthened position. As you lower the right leg and left arm, reach them farther out, grasping the floor with your fingers. You’ll now feel very long across one diagonal. Proceed to the second side. Work through each diagonal several times, letting the limbs come higher off the ground as you feel your center opening and releasing. Then rest in Child’s Pose to release your back (kneeling with your buttocks on your feet, your torso stretched out between your thighs, and your arms comfortably at your sides).

Locust Pose Salabhasana Variation A

Throughout these variations, try lifting into the postures on an exhalation. Exhaling causes a natural toning in the internal organs and the abdominal muscles, making it easier to feel the digestive tract offering support to the spine. Coming into these poses on an exhalation is especially helpful for anyone with a weak or hypermobile back. On the other hand, stiff practitioners may find coming up on an inhalation allows them to lift more easily. Experiment to see which option feels more comfortable for you. Again stretch out on the floor, facedown. Place your arms by your sides with the palms facing the thighs and the fingers stretching back towards the feet. Visualize your soft internal axis–your digestive tract, parallel to your spinal column. Breathe into your inner body; when you feel a connection to your core, slowly bring your torso up off the floor on an exhalation, keeping your hips and legs firmly grounded (Fig. 2).

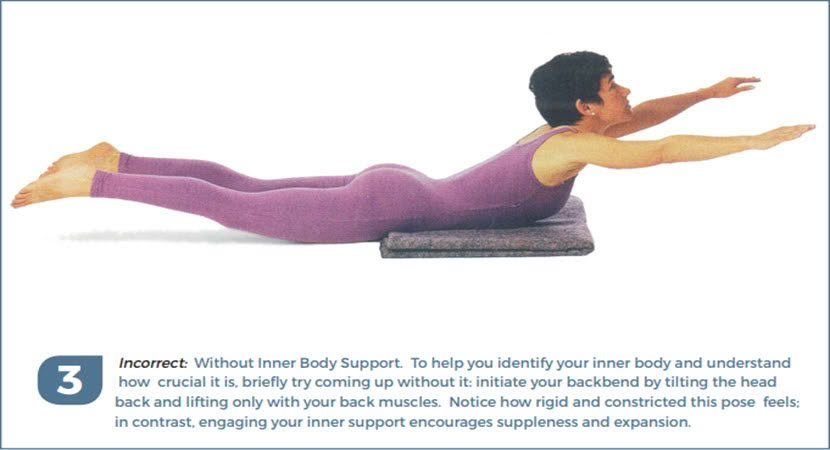

Again imagine lifting yourself up like an inchworm, drawing your front body up into your back body. It’s essential that you keep the head and neck in a neutral position. Gaze just slightly in front of you on the floor. If you contract and lift yourself with the extensor muscles at the back of your neck, drawing the chin up, these powerful muscles will override not only the more subtle flexor muscles in the front of the body, but also the tone throughout your digestive tract (Fig. 3). Take three complete breaths, raising yourself a little higher on each successive exhalation. Sense the continuity in your soft inner body all the way from your mouth to your anus, and feel how this internal energy line mirrors the connection between your skull, your bony vertebral column, and your tail. Then lengthen the lines in both your inner body (from mouth to anus) and your outer body (from head to tail).Notice how light your back feels as you engage the support of your inner body. Repeat this variation three times before resting in Child’s Pose.

If you find it difficult to feel a connection to your digestive tract, try coming up without using its support. On an exhalation, lift your chin toward your forehead, throwing your head back, and lift yourself up using only your back muscles (Fig. 3). Notice how the front body hangs heavily, requiring your back muscles to work twice as hard as before. Also, notice how your body responds now that your level of perception (where you look with your eyes) is higher than your level of movement engagement (the actual angle of your body). How does this feel different from keeping them on the same level? Stay for a moment and then relax and try Salabhasana again. Now feel the support your inner body gives your pose.

Locust Pose Salabhasana Variation B

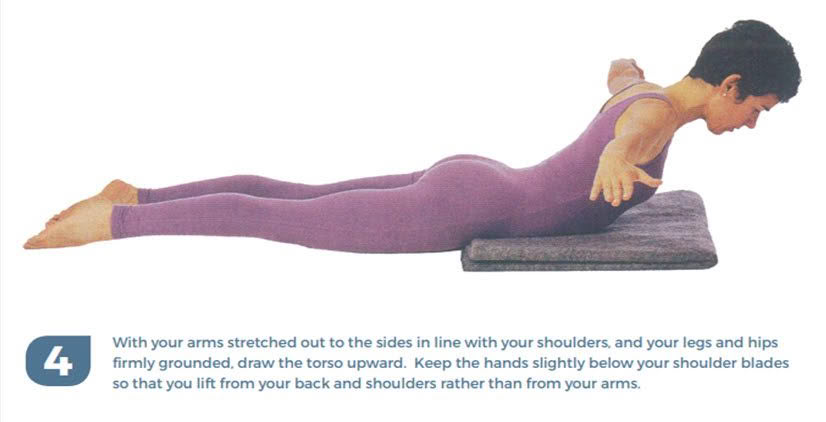

In this variation, bring your arms out to your sides in line with your shoulders. On an exhalation, raise your head, chest, and arms off the floor while allowing the legs to rest firmly on the ground (Fig. 4). Again check to make sure you’re not rocking the skull back onto the cervical spine. When you compress your neck like this, you effectively cut off your consciousness from the neck down, making it almost impossible to feel sensations in the rest of your body.

As you come up off the floor, check that your hands are no higher than your shoulder blades. Instead of initiating the movement from your arms, begin by drawing your trunk off the floor. Imagine being lifted from the nape of the neck by a big mama cat. Feel your front body drawing up to offer its support to your back muscles. Reach your arms out strongly and feel the expansion across the back of your chest as you broaden through the front. Take a few breaths as you maintain the asana, then, on an exhalation, release. After several repetitions, relax once more in Child’s Pose.

Locust Pose Salabhasana Variation C

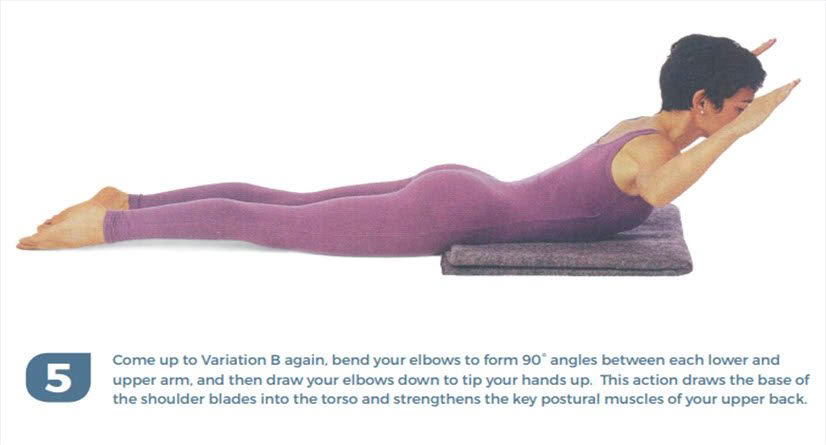

Return to Variation B, coming up off the floor on an exhalation. Take another breath in, and as you exhale, bend your elbows to form 90° angles between each lower and upper arm.

Now comes the challenging part. Slowly tip your elbows down as you raise your forearms and point your hands up at a slight angle (Fig. 5). Check to make sure that each forearm and hand form a straight line; often people simply flex at the wrists rather than properly engaging their arms and shoulders. When you tip the elbows correctly, you’ll feel strong work in the muscles at the base of your shoulder blades. This variation is especially good for strengthening these muscles, which become overstretched and weak in people who chronically slouch or have a rounded back.

As you feel this deep level of muscular engagement, continue to draw support from your inner body. Maintain a constant connection between your digestive tract and your back body. The more you practice moving from the support of your digestive tract, the stronger this support will become. Instead of conceiving your inner body on a purely intellectual level, you will begin to have a direct felt connection to these parts of your body.

Do this variation only once, so you don’t tire yourself out before practicing the final variation.

Full Locust Pose Salabhasana

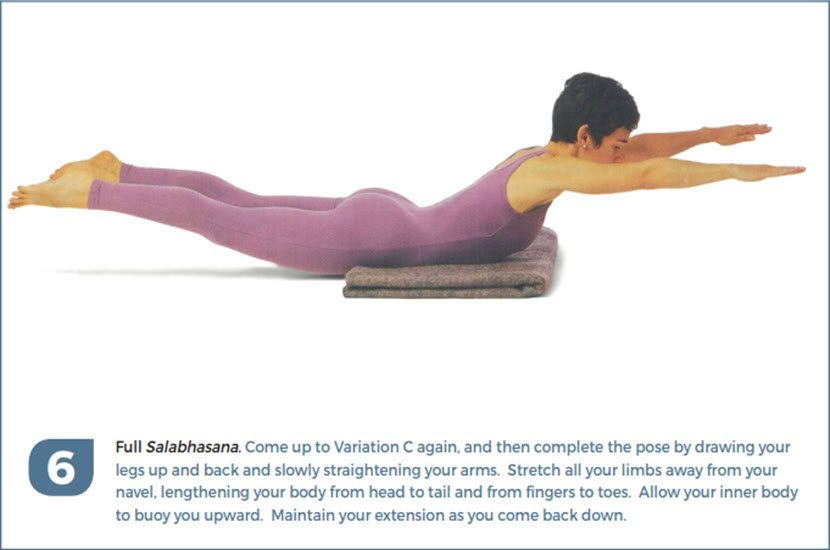

Classically, Salabhasana is taught with both arms and legs lifting simultaneously, but this approach places a very abrupt weight increase on the lumbar spine and can harm those of us with weaker backs. The following variation is not only safer, but also feels pleasant, and thus may encourage you to feature Salabhasana more frequently in your home practice.

Start from Variation C, tipping the elbows down and engaging the muscles at the base of the shoulder blades. Then, on your exhalation, slowly begin to straighten your arms. Pause as you inhale, and then straighten further on your next exhalation. Also, as you straighten your arms, begin to lift both legs off the floor, opening the legs and arms away from your navel center (Fig. 6).

Find the height where you feel the clearest connection between your navel and all your limbs–head, tail, arms, and legs. If your lower back muscles signal that they have reached their maximum safe contraction, come back down to the point just before you feel this potential strain. You may only be able to straighten your arms halfway. Don’t worry about how far you can lift into the pose; if you work correctly and compassionately with what you can do, you will build up steadily to the final variation.

As you extend all your limbs into space, open into the pleasure of releasing your back in a long, smooth arc. Feel both your front and back body going along for the ride. Again, make sure you don’t rock your skull back onto your cervical spine in an attempt to lift your head higher. Keep your neck softly engaged, your eyes relaxed, and the crown of your head reaching forward. Eventually, as you can lift your entire pose higher, your head and gaze will rise as well.

As you come out of the pose, reach even farther with your hands and feet, eventually grasping the floor with your fingertips. Maintaining this firm connection, draw your tailbone under, giving the entire spine a deep release. Notice how this reaching action of the tailbone takes any slack out of your digestive tract.

Once you learn each variation, you can link them together into a moving series. The series might look something like this:

As you exhale, come up into Variation A. On your inhalation, maintain your position, and then move into Variation B as you exhale. Again, maintain your position as you inhale, and then move into Variation C on your exhalation. Maintain your lift as you inhale, and then, as you exhale, simultaneously begin to extend your arms and legs away from each other and into your final pose. Stay in Salabhasana for a few more breaths, and then release. Rest in Child’s Pose, and then, if you wish, repeat the sequence several more times.

You may want to balance your practice by following Salabhasana with a few gentle twists or by drawing your knees up to your chest while lying on your back.

When you’re ready to relax in Savasana, notice the focus of attention in your body. Are you feeling more aware of your interior body than at the beginning of your practice? Release completely into Savasana, and when you feel completely refreshed, roll over on your side. As you come up to standing, feel how this new awareness of the soft central axis of your body can contribute to lightness in your standing and sitting posture.

This article originally appeared in Yoga International magazine, March/April 1999. Photographs by Bill Reitzel. © 2023 by Donna Farhi.

This article is from a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana and will be followed in the next post by an addendum: New Insights. There Donna shares what has changed, since the original article was published, after more than three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus article will be included. None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts