July 24

by Donna Farhi

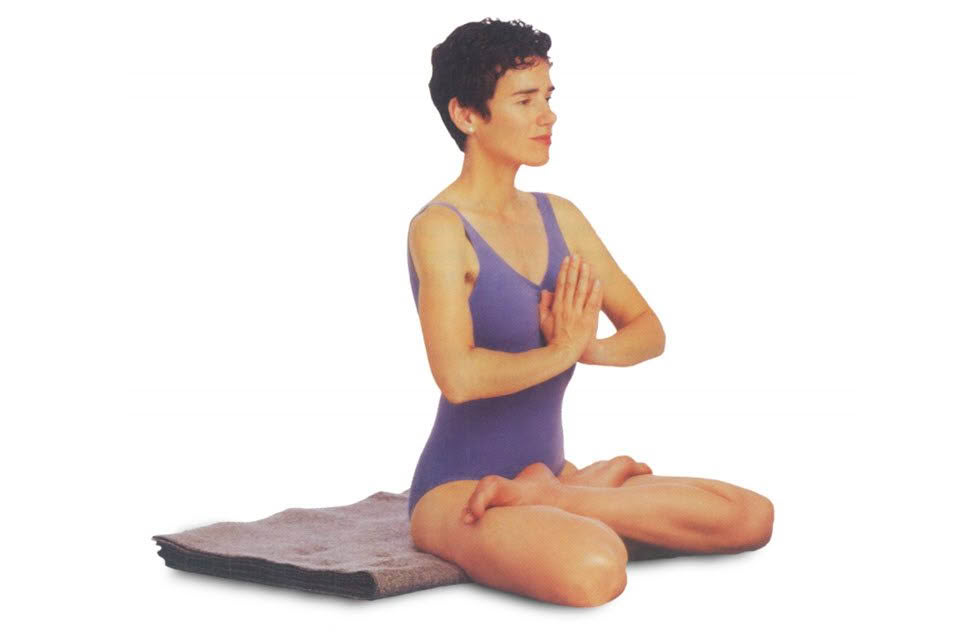

Let this quintessential meditation pose teach you to focus on your path, not on your destination.

Benefits

Contraindications

Dear Reader

Please keep in mind that the images in this column were scanned from original archived articles and the quality might sometimes vary.

As soon as you admit that you practice Yoga, you’re likely to be confronted with the question, “So, can you do that pretzel thing with your legs?” Lotus Pose (Padmasana), a.k.a. ‘the pretzel’, more than any other asana, is synonymous in the public’s mind with the practice of Yoga. And if you are like me, unable for the first 10 years of practice to even approximate Padmasana, you would have to doggedly admit that, no, you don’t do Lotus, and then face suspicion that you must be some kind of Hatha Yoga dilettante.

Whether it’s Padmasana or some other posture, almost everyone has difficulty doing certain movements. Usually, as you attempt such an asana, your key limitations are brought to the forefront of your attention. When I began practicing Yoga at the age of 16, I believed that the purpose of practice was not only to identify these weak links, but to eliminate such ‘problems’. For many years my practice became an obsessive ritual centered around eradicating these ‘defects’. Much of my time on the mat, I am sad to say, was spent feeling frustrated, unhappy, and dissatisfied. My happiness and sense of self worth were always contingent on solving my body’s ‘problems’.

Many of my conditions did improve as a result of practice, but 22 years later, I continue to be astonished at the intransigent nature of some parts of my body. While it’s true that Hatha Yoga is a remarkably effective practice for balancing the body and mind, and while I’ve benefited enormously from the positive changes that have come with the practice, it is also true that some parts of my body have remained, for want of a better word, problematic. My lower back, congenitally weak, demands respect and limits my ability to backbend; my shoulders, upper back, and neck tend toward stiffness; and my right hip, seriously compromised in a dancing injury, for years made Lotus Pose a special challenge for me.

Perhaps you too have noticed niggling parts of your body where tension always accumulates. Whether caused by an accident, your constitutional nature, habit, or a tension that mysteriously and predictably appears like a bird that returns to the same tree every summer, these difficult spots rarely vanish completely, even in the face of tenacious, disciplined practice. Just for a moment, let us postulate that these stubborn parts of the body serve some useful purpose. Could they represent some kind of stabilizing force in your personality? Although the idea of waking up tomorrow with a perfect body might sound tempting, I imagine this cataclysmic change would be so sudden as to shatter the psyche. The person you have come to know after so many years would have disappeared. But perhaps you still need this person. The glacial rate at which change often occurs allows you to shift the scaffolding of your personality slowly enough to do no damage and gives you time to integrate new openings and releases.

Each and every difficulty I have encountered in my body has taught me something. My tight right hip and 10-year introduction to Padmasana taught me compassion for my injured body. It also taught me to persevere. If I’d been able to crank myself into Padmasana and other difficult poses on the first shot, I might not have continued to practice. Thus my tight right hip has blessed me with years of fruitful Yoga. How thankful I am to have had such a friend. Could any situation have provided me with a more thorough apprenticeship in life than my own innate imperfections?

Irish poet Oliver Goldsmith once said, “There are some faults so nearly allied to excellence, that we can scarce weed out the vice without eradicating the virtue.” If I have learned anything during more than two decades of practice, it is that the purpose of Yoga practice is not to eradicate defects but rather to learn to accept the whole of ourselves, including (and especially) those parts we find infuriating. Practicing Yoga isn’t about fixing all our problems and answering all our questions. It doesn’t mean that one day we’ll arrive at a pie-in-the-sky existence. In reality, some things are not fixable. In fact, if we achieve any equanimity at all, it’s only a reflection of our skill at acceptance— our skill at living with our questions rather than having answered them. An even greater challenge is to not just begrudgingly accept our questions and imperfections, but to embrace them so that we enjoy our practice in spite of our difficulties.

It’s All in the Hips

Here is a sequence of postures that I use to warm up for Padmasana. This sequence assumes that you are already familiar with deep hip opening movements and are able to do Half Lotus without strain or injury to your knee. But, like so many practitioners, you may have become stuck in the transition between doing Half Lotus and lifting that second leg up into the real McCoy. These movements are best done after standing poses, when the body is already warm. If you’re very tight, you may benefit from practicing in the afternoon when the body is naturally more flexible. Begin by staying in each posture for at least a minute (counting 12 to 15 breaths is a good guide).

Your hips are deep joints stabilized by some of the strongest ligaments and muscles in your body. This stability means they are intrinsically less mobile than most other joints. Thus, the hips tend to change rather slowly. In contrast, your knee joint is one of the weakest joints in the body, and its instability makes it more mobile. Relative to the hip, the ankle also tends to be unstable. Therefore, when you are working on Padmasana, it is essential that you stabilize both your knees and your ankles as you attempt to free your hips. Otherwise you will damage the less stable joints long before you achieve Lotus.

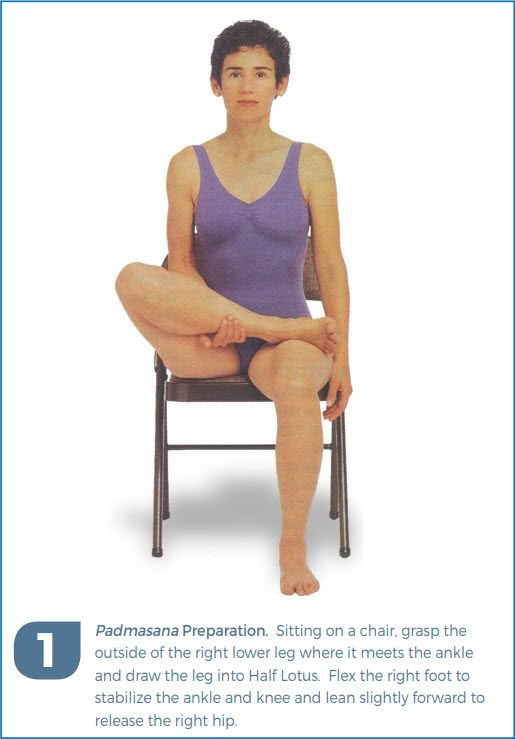

Begin by sitting in a chair and slowly rotating the right leg out at the hip. Place your right ankle just above your left knee. To lift the leg into Half Lotus Pose (Ardha Padmasana), reach your right hand under your calf to grasp the outside of the right lower leg near the ankle (Fig. 1).

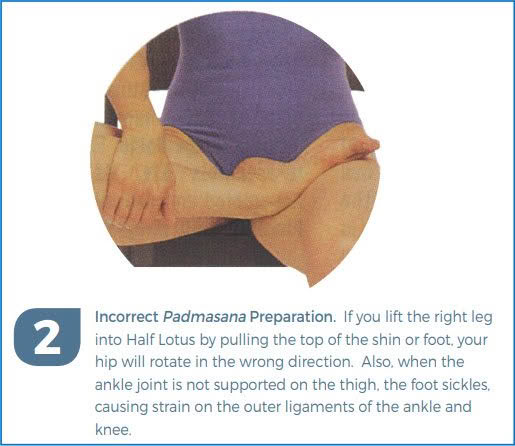

Flex the foot so that you can no longer see the sole, and slowly lift the leg up, rotating the shin and thigh outwards as you do so. Carefully place the ankle on the upper thigh near your groin, with the outer ball of the ankle joint supported by your thigh. Continue to draw the little toe of your right foot back towards your outer knee to prevent the rotation from coming at the ankle or knee. If you pull the leg up by grasping the top of the foot and allowing the foot to sickle (Fig. 2), you will only overstretch the ligaments of your ankle and knee rather than opening your hip.

The movement of your right knee. towards the floor should be accomplished by a deep rotation in the hip socket, not by sickling the ankle and torquing the knee. Go slowly, and never move further into Padmasana if you experience pain in your knees; they are very unforgiving joints once they are injured.

The movement of your right knee. towards the floor should be accomplished by a deep rotation in the hip socket, not by sickling the ankle and torquing the knee. Go slowly, and never move further into Padmasana if you experience pain in your knees; they are very unforgiving joints once they are injured.

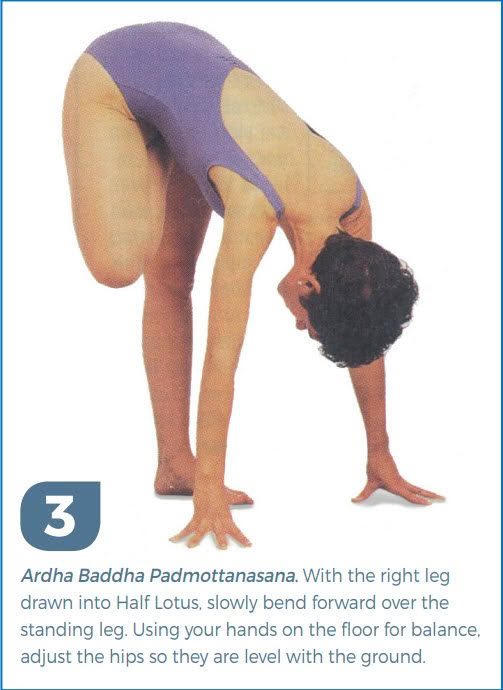

Ardha Baddha Padmottanasana

Stand in Mountain Pose (Tadasana) and gently draw your right leg up into Ardha Padmasana. Slowly bend forward over the standing leg, extending from the heel of the right foot high up into the groin. Using your hands on the floor for balance, adjust the hips so they are level with the floor (Fig. 3). Consciously focus on releasing the femur of the Lotus.

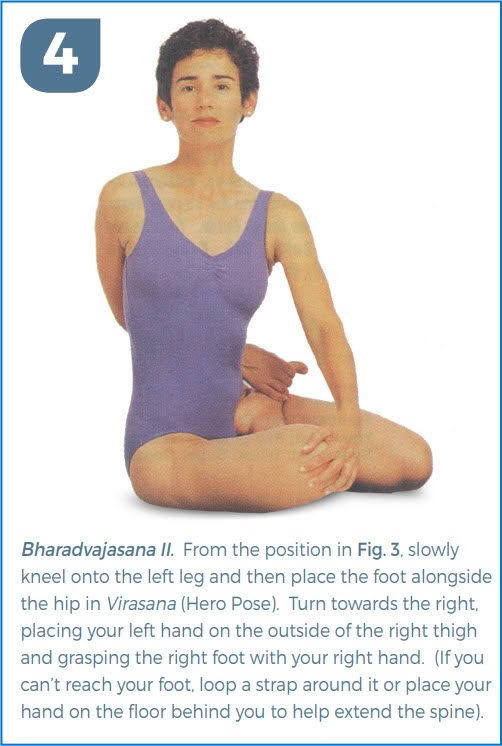

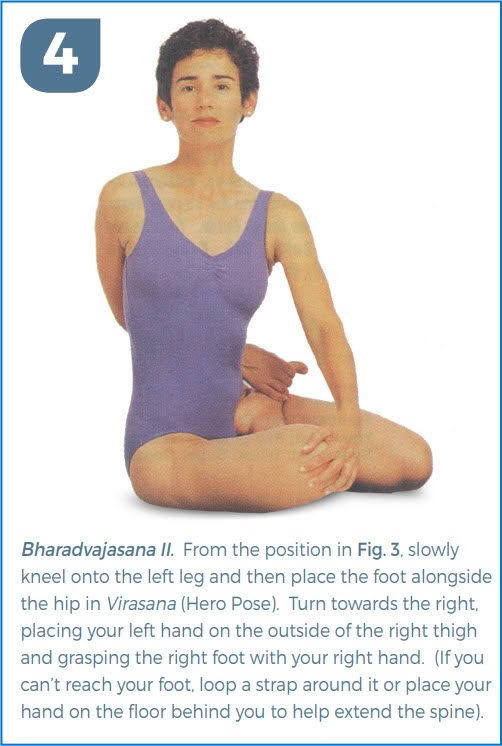

Bharadvajasana II (Sage Pose II)

Carefully place the left knee, shin, and foot on the floor in a kneeling Virasana (Hero Pose). Your right leg will still be in Lotus. If your right knee is off the floor, place soft but firm support (a towel or rolled mat) under the knee. As you exhale, turn your belly towards the right, placing your left hand on the outside of your right thigh.

Bharadvajasana II (Sage Pose II)

Carefully place the left knee, shin, and foot on the floor in a kneeling Virasana (Hero Pose). Your right leg will still be in Lotus. If your right knee is off the floor, place soft but firm support (a towel or rolled mat) under the knee. As you exhale, turn your belly towards the right, placing your left hand on the outside of your right thigh. Then, cup your right knee in your left palm so that the fingers point back

Then, cup your right knee in your left palm so that the fingers point back toward your outer right hip. In this position you can gently draw the femur out of the socket as you turn into the twist. (This will create space and freedom in the hip joint.) Reach around and catch hold of the right foot with your right hand. If this is not possible, bring the right hand onto the floor behind you and use it as a support to keep the spine erect. As you inhale, focus on lengthening up through your spine; as you exhale, allow the torso to move more deeply into the twist (Fig. 4). Because we’re using the posture to prepare for Lotus, don’t be concerned with doing your maximum twist. Instead, concentrate on drawing your right femur out of the socket as you release the right side of the pelvis back away from the femur. Breathe slowly and remain in the pose for at least a minute.

If you are unable to reach behind you to hold the foot of the Lotus leg in Bharadvajasana II, bring both hands forward onto the floor in front of you for support and bend forward as far as is comfortable. Bring your awareness deep into your hip sockets. Notice that the intensity of the sensation varies with the incoming and outgoing breath and the pauses in between. Use the moments where the sensation is less intense to soften and release any tension that arises in response to the asana.

toward your outer right hip. In this position you can gently draw the femur out of the socket as you turn into the twist. (This will create space and freedom in the hip joint.) Reach around and catch hold of the right foot with your right hand. If this is not possible, bring the right hand onto the floor behind you and use it as a support to keep the spine erect. As you inhale, focus on lengthening up through your spine; as you exhale, allow the torso to move more deeply into the twist (Fig. 4). Because we’re using the posture to prepare for Lotus, don’t be concerned with doing your maximum twist. Instead, concentrate on drawing your right femur out of the socket as you release the right side of the pelvis back away from the femur. Breathe slowly and remain in the pose for at least a minute.

If you are unable to reach behind you to hold the foot of the Lotus leg in Bharadvajasana II, bring both hands forward onto the floor in front of you for support and bend forward as far as is comfortable. Bring your awareness deep into your hip sockets. Notice that the intensity of the sensation varies with the incoming and outgoing breath and the pauses in between. Use the moments where the sensation is less intense to soften and release any tension that arises in response to the asana.

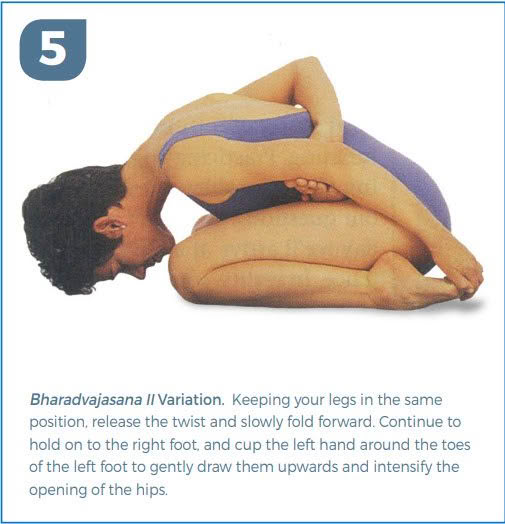

Bharadvajasana II Variation (Sage Pose II Variation)

As you release the twist, turn to face forward between the two legs. If you were able to hold your right foot, continue to do so. Reach around with your left hand and cup the ball and toes of your left foot with the palm of your left hand. As you slowly bend forward from your hips, use your left hand to gently draw the toes of your left foot up toward the ceiling. This action will increase the rotation of your pelvis around your femur. Rest your head on the floor in front of you (or on a folded blanket if coming down all the way is too intense) (Fig. 5).

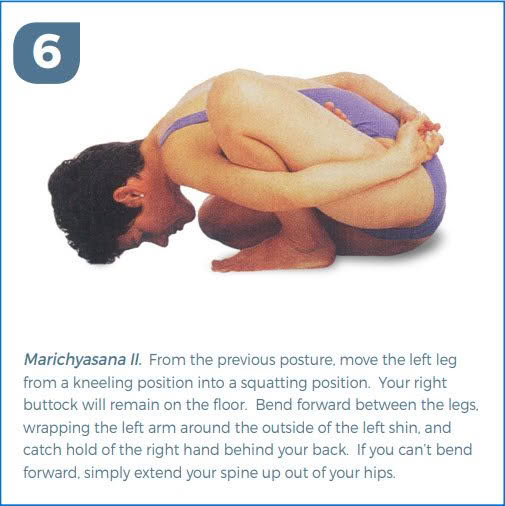

Marichyasana II

Now place your hands on either side of your body. Lean onto the right hand as you release the left leg from Virasana and bring it into a deep squatting position. Your right buttock will remain on the floor. Draw your spine up out of your hips and extend forward as far as possible. The first time you attempt the pose you may feel very awkward. Persist. This asana is truly amazing for releasing the hips and providing a deep abdominal massage, even if all you can manage at first is to lean slightly forward. With time, you will be able to bend forward between the two legs, wrap the left arm around the outside of the left shin, and catch hold of the right hand behind your back (Fig. 6).

This movement places you in a very compact forward bend, with your right leg in a deep Lotus position and your left in a deep squat. (It’s okay to let the left sit bone come slightly off the ground.

The heel of the right foot will be pressed into the junction of the descending colon and the sigmoid colon on the left side of your abdomen. This area of the colon tends to become congested, so the deep pressure of your heel provides a very beneficial self-massage. Eventually, when you switch sides, your left heel will massage the area of the iliocecal valve (the junction of the small and large intestine) on the right side if the lower abdomen.

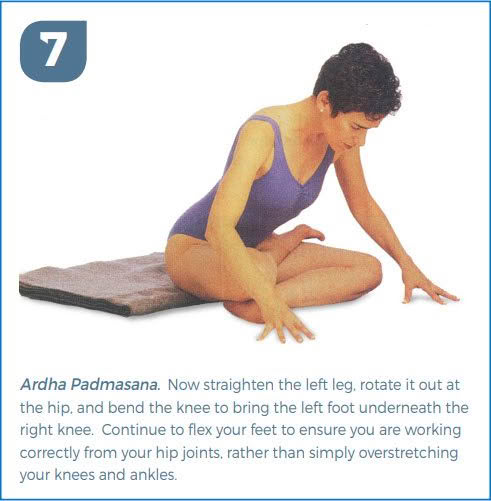

Ardha Padmasana (Half Lotus)

To transition into Half Lotus, bring your left leg forward, rotating the leg out. Bend your left leg, and place the foot underneath your right knee. Actively flex the left ankle. In this position you should be unable to see the sole of either foot. Maintaining this integrity through both ankles, lean slightly forward, resting your weight on your fingertips (Fig. 7). You may find that a folded blanket under your hips helps you bend forward. Tip forward until you feel a strong opening sensation within your hip sockets. Stay here and breathe for at least a minute.

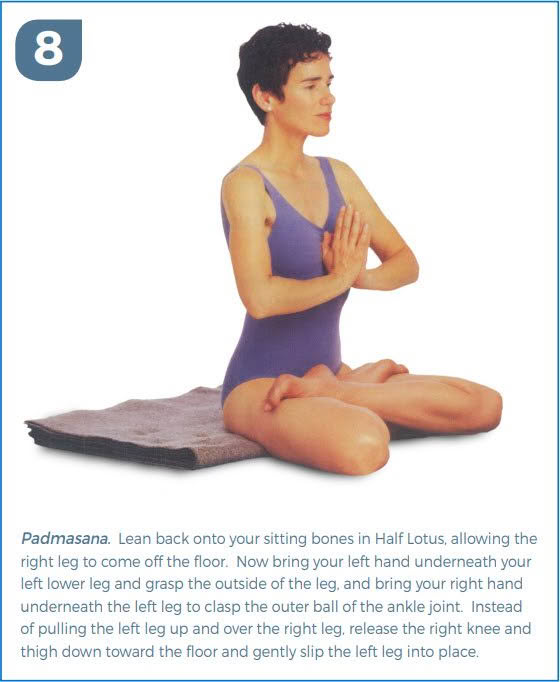

Padmasana (Lotus Pose)

If your right knee was close to or touching your left foot in Ardha Padmasana, you are probably ready to make an attempt at full Padmasana. Here is a method of entering Padmasana, taught to me by Dona Holleman, that is much, much safer than the common strategy of pulling the second leg up into the pose. In Half Lotus, lean back until you are balanced on the back of your sitting bones, allowing the right leg to come off the floor. Now bring your left hand underneath your left lower leg and grasp the outside of the leg, and bring your right hand underneath the leg to clasp the outer ball of the left ankle joint. Slowly lift the left leg off the floor, allowing the leg to be completely relaxed. Instead of pulling this leg up and over the right leg, release the right knee and thigh down toward the floor. Breath by breath, allow the right leg to rotate further outward. When the right leg comes level to or lower than the left, you will be able to gently slip the left leg over the top of the right. Then you can rest both legs back down onto the floor (Fig. 8). You may find additional blankets under your pelvis aid you in this movement. It’s normal for the top knee in Padmasana to be slightly off the floor, but you should place a soft but firm support under the knee if it is more than an inch in the air.

Remain in Padmasana for as long as you are comfortable and then slowly release the legs. Straighten both legs along the floor in front of you. Using both hands, press firmly down on the tops of the shins just below the knees. This will help release the interior knee joint.

Remember that Lotus is an asymmetrical pose that causes a slight rotation through your spine, so it’s important to be balanced in your efforts. If there is a huge difference between the flexibility of your two hips, you have even more reason to work on Padmasana on both sides. If you are unable to move as far toward full Lotus on one side, you can still progress by simply repeating the variations you can do or holding those variations longer on your tighter side.

When you complete the series (or as much of it as you can do safely), take a moment to sit quietly. Acknowledge the efforts you have made, regardless of the results, and give thanks for the gift of your body and the gift of practice. If you feel frustrated, dissatisfied, or unhappy with the outcome, face these feelings honestly. Then consider that you have a choice. There will never be an end to personal failings, and thus no end to the struggle to eradicate them. You can continue to fight with your shortcomings, or you can perceive your failings with humor and lightheartedness.

It’s not hard to accept wonderful things in life, either in yourself or in others. But it’s a tall order to accept even the smallest unpleasant thing about someone else or yourself. Yet the purpose of Yoga practice is to accept yourself and the world unconditionally. This acceptance is the root of all compassion. Without compassion, practice breeds an insidious form of self-hatred and intolerance, not only for your own perceived foibles, but for those of others. If you hate your right hip or your shoulder or your rounded upper back, how different is this from hating someone because they have acne, a stutter, or a limp? If self-acceptance is the purpose of practice, then what better conditions could you ask for than your own deep holding points, your weaknesses, your intransigent habits, available to you (free of cost!) every day of your life. Self-acceptance doesn’t mean that you become complacent, or that you don’t try to heal injuries, or that you don’t seek help for pain. It doesn’t mean that you practice half-heartedly. It means that you attempt to cultivate self-acceptance despite everything you know about yourself.

Ultimately, self-acceptance also means that peace of mind is never contingent on outcome. Now, as I practice yet again, slowly loosening my right hip, it is no longer a source of frustration. Over the years, it has softened enough to open into Padmasana.

This article is from a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana and will be followed in the next post by an addendum: New Insights. There Donna shares what has changed, since the original article was published, after more than three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus article will be included. None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

This article originally appeared in Yoga Journal magazine, Nov/Dec 1999. Photographs by Bill Reitzel. © 2023 by Donna Farhi

share this

Related Posts