Subtotal: $74.00

April 10

by Donna Farhi

“First of all the twinkling stars vibrated, but remained motionless in space, then all the celestial globes were united into one series of movements... Firmament and planets both disappeared, but the mighty breath which gives life to all things and in which all is bound up remained.”

-Vincent van Gogh

Just as there is an invisible force that produces the organic symmetry of a towering pine’s branches, the spiral vortex of an ocean wave, and the endless cycle of days and nights that governs our lives, so, too, our human bodies are governed by intrinsically intelligent patterns.

From the extraordinary moment when egg and sperm are ignited into being, our bodies form a design unlike any other that has ever been or will ever be through a wondrous process that is both a replication of an ancient blueprint and a uniquely individual expression. Our cells multiply and divide, expanding and differentiating into the specific expression that makes us unique, condensing and disappearing back into this same matrix when we die. The inner scaffolding of bones, the tensile fiber of muscles, the processing organs, innervating nerves, and the oceanic fluid systems of the body are arranged into the symphony we call the human body. But these structures alone do not make a body. Just as a light bulb is useless until it is connected to electricity, the raw substance of our body does not become human until it is infused with the force of life. This mysterious life force expresses itself through the projection of light from our eyes; it circulates the blood through our hearts, and causes the ceaseless cycle of inspiration and expiration.

This life force also provides us with a blueprint for optimal movement in the form of universal movement patterns that govern all our actions. These patterns organize our intentions into effortless action. The patterns are programmed into our bodies to permit us to move with ease and power. Some arise as if by an internal time clock, just as we might expect a baby to begin speaking by a certain month. Others happen through our desire to explore the world; the first push from a leg or reach of a fingertip taking us toward a beckoning father or colorful toy. They

From the extraordinary moment when egg and sperm are ignited into being, our bodies form a design unlike any other that has ever been or will ever be through a wondrous process that is both a replication of an ancient blueprint and a uniquely individual expression. Our cells multiply and divide, expanding and differentiating into the specific expression that makes us unique, condensing and disappearing back into this same matrix when we die. The inner scaffolding of bones, the tensile fiber of muscles, the processing organs, innervating nerves, and the oceanic fluid systems of the body are arranged into the symphony we call the human body. But these structures alone do not make a body. Just as a light bulb is useless until it is connected to electricity, the raw substance of our body does not become human until it is infused with the force of life. This mysterious life force expresses itself through the projection of light from our eyes; it circulates the blood through our hearts, and causes the ceaseless cycle of inspiration and expiration.

This life force also provides us with a blueprint for optimal movement in the form of universal movement patterns that govern all our actions. These patterns organize our intentions into effortless action. The patterns are programmed into our bodies to permit us

to move with ease and power. Some arise as if by an internal time clock, just as we might expect a baby to begin speaking by a certain month. Others happen through our desire to explore the world; the first push from a leg or reach of a fingertip taking us toward a beckoning father or colorful toy. They manifest as a series of overlapping and mutually dependent patterns, a language of movement that gives us kinesthetic fluency.

We see the underlying play of movement patterns all the time but are rarely aware of the content of what we see. We can identify a person with neurological disorders far in the distance because we are able to see that the pattern of their gait is different from the normal pattern we have grown to recognize. The function of a symbol or pattern enables us to go beyond the limitation of seeing life as fragments and disparate parts and link these parts into a cohesive whole. While we could learn to walk by breaking down the activity into thousands of separate details, each of which are essential to succeed, this would be an impossibly difficult and frustrating way to go about the task. Rather, we learn to move through patterns.

When you find the ‘knack’ of a movement, you have unknowingly found the cohesive movement pattern that was needed to support your action. Because many of the patterns, like the movement of breathing, are governed by lower brain function, reawakening them involves using a different part of the mind than many of us are accustomed to engaging. Unfortunately, most of us have been taught movement in an overly intellectual, one-step-at-a-time way, with some Yoga methodologies breaking down the Yoga postures into a minutia of points and details. If you’ve ever tried to talk yourself up into a handstand by placing your shoulders and your wrists and your head-and so on in exactly the right way, you know how frustrating this can be. It’s like going to a filing cabinet for the information but opening up the wrong drawer. When we learn through patterns, we learn through a more sensate, felt, experiential mode of exploration and discovery. To do this we have to open the mind, becoming childlike so that the body can reveal to us the knowledge with which it was born.

manifest as a series of overlapping and mutually dependent patterns, a language of movement that gives us kinesthetic fluency.

We see the underlying play of movement patterns all the time but are rarely aware of the content of what we see. We can identify a person with neurological disorders far in the distance because we are able to see that the pattern of their gait is different from the normal pattern we have grown to recognize. The function of a symbol or pattern enables us to go beyond the limitation of seeing life as fragments and disparate parts and link these parts into a cohesive whole. While we could learn to walk by breaking down the activity into thousands of separate details, each of which are essential to succeed, this would be an impossibly difficult and frustrating way to go about the task. Rather, we learn to move through patterns.

When you find the ‘knack’ of a movement, you have unknowingly found the cohesive movement pattern that was needed to support your action. Because many of the patterns, like the movement of breathing, are governed by lower brain function, reawakening them involves using a different part of the mind than many of us are accustomed to engaging. Unfortunately, most of us have been taught movement in an overly intellectual, one-step-at-a-time way, with some Yoga methodologies breaking down the Yoga postures into a minutia of points and details. If you’ve ever tried to talk yourself up into a handstand by placing your shoulders and your wrists and your head-and so on in exactly the right way, you know how frustrating this can be. It’s like going to a filing cabinet for the information but opening up the wrong drawer. When we learn through patterns, we learn through a more sensate, felt, experiential mode of exploration and discovery. To do this we have to open the mind, becoming childlike so that the body can reveal to us the knowledge with which it was born.

At first glance through any comprehensive Yoga text it is likely the reader will be overwhelmed by the sheer number and apparent complexity of the Yoga asanas and practices. Yet, because human movement develops logically, we can simplify and at the same time deepen our understanding of these amazing practices by first learning and integrating the underlying movement principles that encompass all movement. This is not merely a physical or mechanical process. Each movement pattern and principle is directly related to an organizing pattern of consciousness. Thus, when you learn to breathe freely, you are also learning to think and live freely. When you learn a simple skill such as standing with ease, you learn about right relationship, trust, and the interconnectedness of all things.

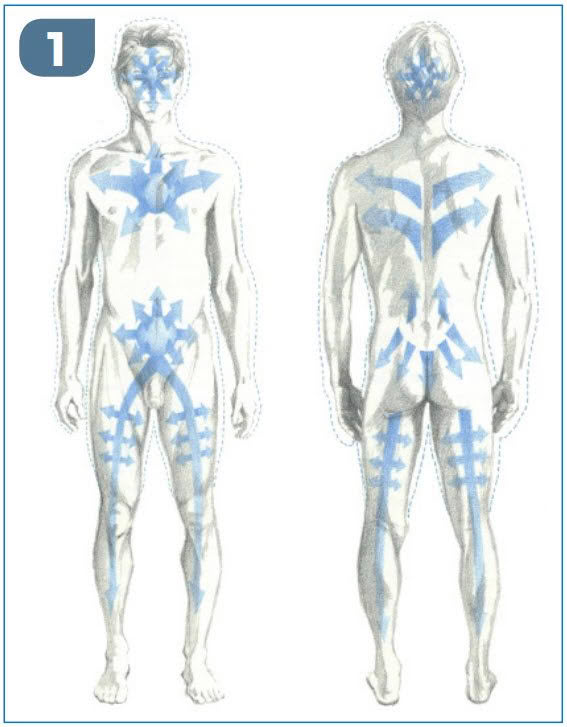

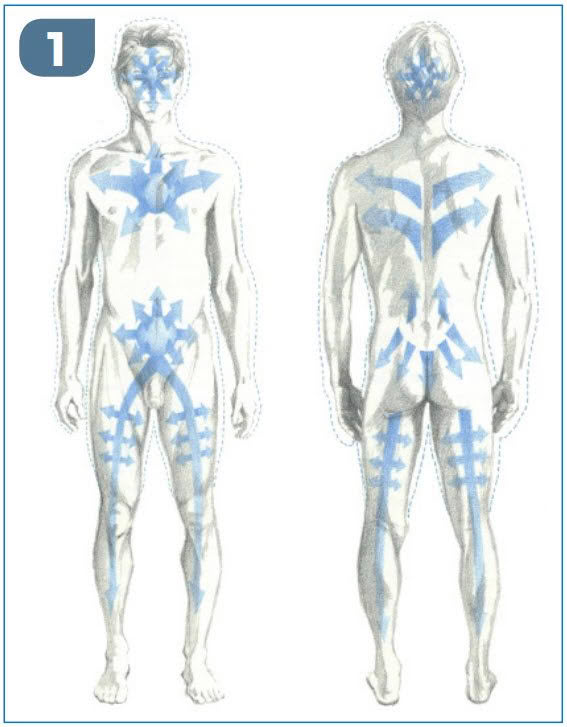

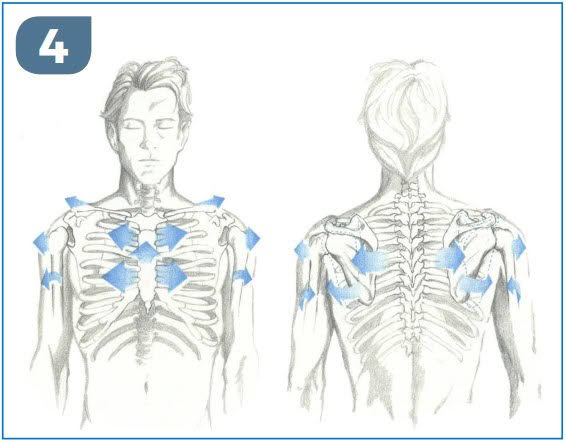

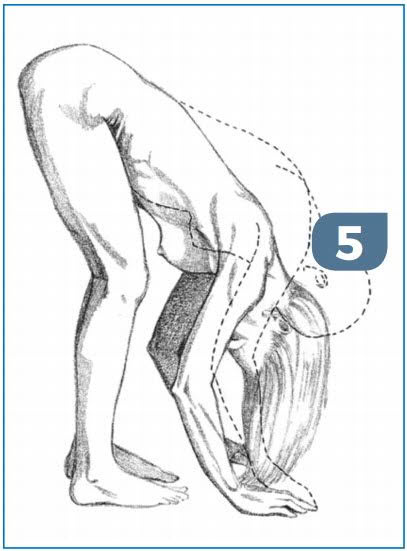

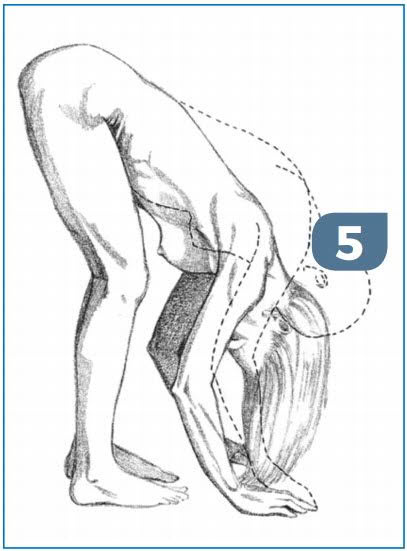

When Yoga was introduced to the West over a century ago, it was taught and adapted in a way that the objective Western mind could understand. While this objectification had the positive effect of planting the seeds of Yoga in a new culture, some of the more profound and meaningful aspects of the practice have been lost or misunderstood. In large part what has been passed on and, unfortunately, continues to be propagated is the form of the practice without the living, vital contents. The Yoga asanas, while appearing relatively static compared to other movements, are actually dances swirling with internal motion. The form of each asana acts as a container for these subtle yet powerful internal movements (Fig. 1). The untrained eye sees no visible movement, but on further investigation, an asana practiced in this vital way is easy to distinguish. When a dancer moves, his actions take him into space, and thus his energy tends to be dissipated by his efforts. In Yoga we direct movement inside the body so that its positive effects serve to cleanse and regenerate us.

When Yoga was introduced to the West over a century ago, it was taught and adapted in a way that the objective Western mind could understand. While this objectification had the positive effect of planting the seeds of Yoga in a new culture, some of the more profound and meaningful aspects of the practice have been lost or misunderstood. In large part what has been passed on and, unfortunately, continues to be propagated is the form of the practice without the living, vital contents.

The Yoga asanas, while appearing relatively static compared to other movements, are actually dances swirling with internal motion. The form of each asana acts as a container for these subtle yet powerful internal movements (Fig. 1). The untrained eye sees no visible movement, but on further investigation, an asana practiced in this vital way is easy to distinguish. When a dancer moves, his actions take him into space, and thus his energy tends to be dissipated by his efforts. In Yoga we direct movement inside the body so that its

positive effects serve to cleanse and regenerate us. The key to rediscovering the original life of the practices does not lie in contrived, artificial techniques that we impose on the body, but rather in listening to the laws of the natural world.

The First Movement

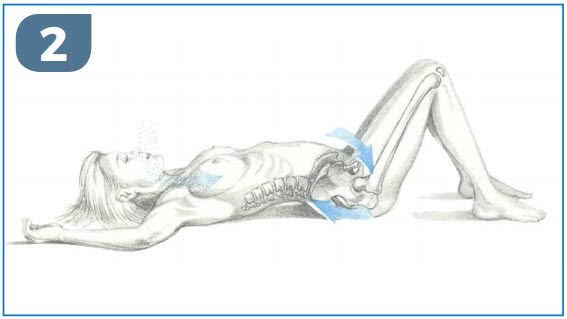

From the moment of conception our bodies begin to breathe. Each cell in the body expands, condenses, and rests in an internal rhythmic pattern, a pattern that will become amplified into full-body breathing at the moment of birth. This first movement is the basic template for our existence. Whether we are sitting still, running up a hill, or sound asleep, the breath acts as a continuous resonant presence infusing and influencing all other processes, from the chemical reactions of our cells to our moment-to-moment psychological and emotional state.

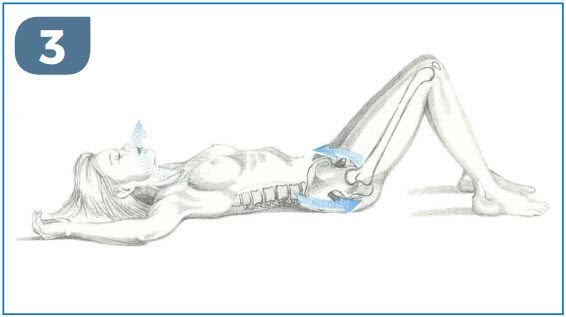

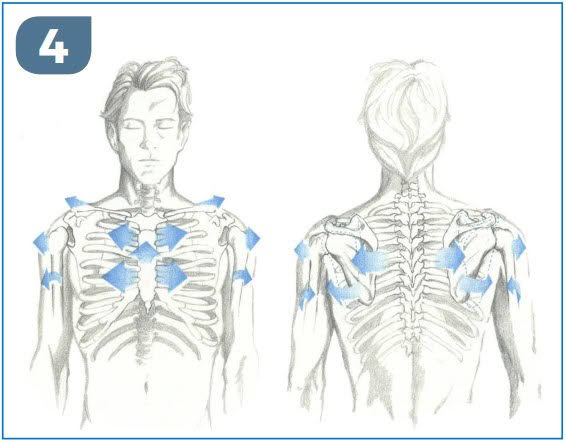

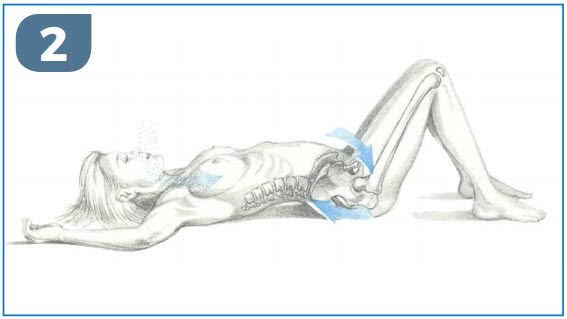

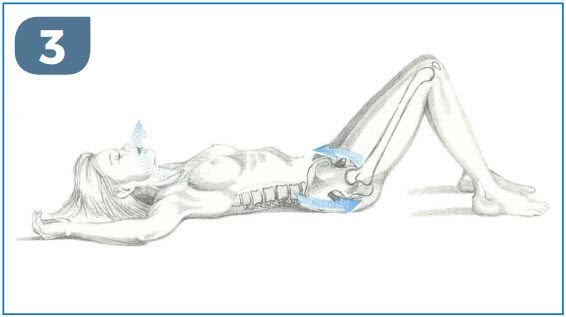

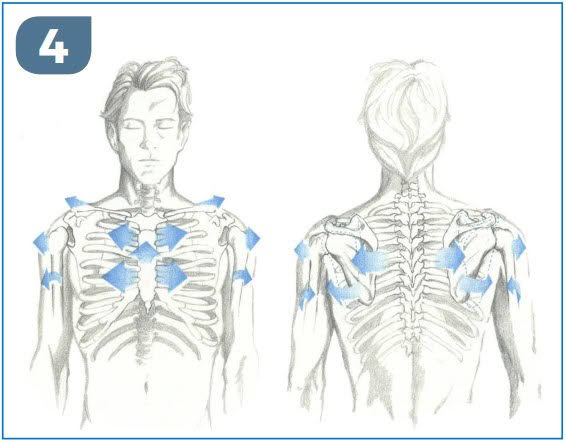

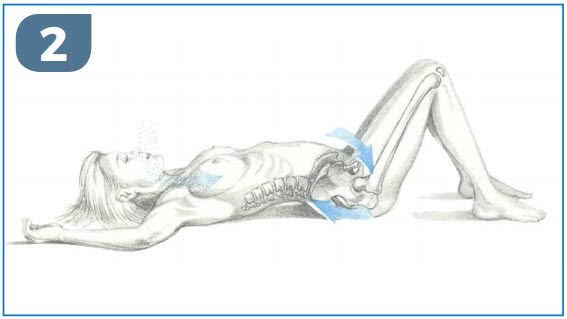

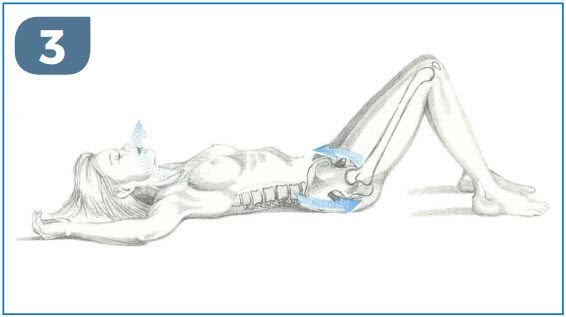

The fundamental nature of the breath is that it is in a constant state of oscillation. Just as the tides ebb and flow, we breathe in and out in an ongoing rhythm that ceases only when we take our last breath. All other physical and psychological patterns build successively from this one central motif (Figs. 2-4). For this reason, if the movement of the breath is restricted or distorted in some way, all other patterns of our movement and consciousness will also be restricted or distorted. Every other process in the body is reliant upon this one central process.

The oscillation of breathing is a perfect mirror of the fluctuations of life. Life is like a swinging pendulum, some changes bringing with them difficulties and pain, and other changes bringing with them ease and joy. If we are open to this process, life will move us. If we are unable to integrate life’s changes, we begin to resist by restricting our breath. When we hold the breath and try to control life or stop changes from happening, we are saying that we do not want to be moved. In those moments our desire for certainty has become much stronger than our desire to be dynamically alive. Breathing freely is a courageous act. What we discover is that our desire for stasis, our clinging to the life we know, and our bending of every situation to the security of our mental constructs are the very things that destroy our creativity and ability to live freely. Breathing happens to us when we remove the obstacles we have erected to its free movement. As such, the most common misunderstanding about breathing is that it improves through a forceful effort of the will. Anyone who has tried to breathe deeper through aggressive strategies knows that mechanical efforts to breathe better only result in making the breathing more restricted and more limited.

The fundamental nature of the breath is that it is in a constant state of oscillation. Just as the tides ebb and flow, we breathe in and out in an ongoing rhythm that ceases only when we take our last breath. All other physical and psychological patterns build successively from this one central motif (Figs. 2-4). For this reason, if the movement of the breath is restricted or distorted in some way, all other patterns of our movement and consciousness will also be restricted or distorted. Every other process in the body is reliant upon this one central process.

The oscillation of breathing is a perfect mirror of the fluctuations of life. Life is like a swinging pendulum, some changes bringing with them difficulties and pain, and other changes bringing with them ease and joy. If we are open to this process, life will move us. If we are unable to integrate life’s changes, we begin to resist by restricting our breath. When we hold the breath and try to control life or stop changes from happening, we are saying that we do not want to be moved. In those moments our desire for certainty has become much stronger than our desire to be dynamically alive. Breathing freely is a courageous act. What we discover is that our desire for stasis, our clinging to the life we know, and our bending of every situation to the security of our mental constructs are the very things that destroy our creativity and ability to live freely. Breathing happens to us when we remove the obstacles we have erected to its free movement. As such, the most common misunderstanding about breathing is that it improves through a forceful effort of the will. Anyone who has tried to breathe deeper through aggressive strategies knows that mechanical efforts to breathe better only result in making the breathing more restricted and more limited.

The fundamental nature of the breath is that it is in a constant state of oscillation. Just as the tides ebb and flow, we breathe in and out in an ongoing rhythm that ceases only when we take our last breath. All other physical and psychological patterns build successively from this one central motif (Figs. 2-4). For this reason, if the movement of the breath is restricted or distorted in some way, all other patterns of our movement and consciousness will also be restricted or distorted. Every other process in the body is reliant upon this one central process.

The oscillation of breathing is a perfect mirror of the fluctuations of life. Life is like a swinging pendulum, some changes bringing with them difficulties and pain, and other changes bringing with them ease and joy. If we are open to this process, life will move us. If we are unable to integrate life’s changes, we begin to resist by restricting our breath. When we hold the breath and try to control

life or stop changes from happening, we are saying that we do not want to be moved. In those moments our desire for certainty has become much stronger than our desire to be dynamically alive. Breathing freely is a courageous act. What we discover is that our desire for stasis, our clinging to the life we know, and our bending of every situation to the security of our mental constructs are the very things that destroy our creativity and ability to live freely. Breathing happens to us when we remove the obstacles we have erected to its free movement. As such, the most common misunderstanding about breathing is that it improves through a forceful effort of the will. Anyone who has tried to breathe deeper through aggressive strategies knows that mechanical efforts to breathe better only result in making the breathing more restricted and more limited.

Breathing is both a process that happens unconsciously or automatically and a process that can be controlled consciously through the will of our minds. At one end of a continuum breathing remains unconscious so that we can go about our business without having constantly to think about taking a breath in or out. At the other end of the continuum breathing can be controlled and manipulated. The Yogis developed sophisticated protocols for unleashing the power of the breath, called pranayama practices. The root word pra denotes constancy, and na means movement. Therefore prana is a force in constant motion. In between these two ends of the continuum lies a third possibility, one that should precede any formal pranayama practice, and that is the place where we simply become conscious of being breathed. We allow this essential breathing to happen to us naturally.

Becoming attuned to your breath is like learning to dance the waltz with another person. At first you have to become familiar with your dance partner––how he moves, when he moves, and where he moves. To be a good dance partner with the breath you must be suggestible and let the wisdom of the breath guide all of your movements. As you learn to follow the lead of the breath, you will know what to do next. I call this ‘moving inside the breath’. At other times, when you do not have a connection to your breath, you are moving ‘outside’ the breath. When you do this, it will feel like dancing the waltz by yourself. As you become more masterfully attuned to your breath, the division between leader and follower dissolves and all that is left is the dance itself.

The Process of Inquiry

The following inquiries are intended to encourage attunement with the breath. They are distinctly different from the exercises so familiar to the Western practitioner. The word ‘exercise’ usually implies some kind of repetitive activity (often unpleasant) that we will ourselves to do. Doing an exercise also assumes there is a set result we are trying to achieve, and the foreknowledge of this ‘correct’ result tends to color our perceptions of that which is expected of us.

The purpose of the inquiries is to provide you with a situation in which you can explore and discover new skills for yourself. As you enter an inquiry the most important attitude to bring with you is one of inquisitiveness and open-mindedness. If there is no ideal to the process of perception, then anything you feel or sense is worthy of your observation. No movement, thought, or impulse is insignificant in open awareness. There is no good or bad perception. This non-discriminatory awareness will allow you to go far beyond the limited perspective that is your lot when your sole concern is to ‘get it right’. Surely it was this same process of experimentation that allowed the ancient Yogis to discover the vast and creative range of practices handed down to us today. It is only through a recapitulation of this process that we can discover the inner meaning of the practice and go beyond mechanical repetition.

First Inquiry: Letting the Breath Move You

Stand with your feet hips-width apart. Bend your knees generously and allow your spine to fold forward over your legs (Fig. 5). Let the head, neck, and the arms drape. If this position is uncomfortable because of the tightness along the back of your legs or in your spine, you can fold forward sitting in a chair with your feet wide apart. In this variation your head will hang between your legs and your arms will drape along the outside of your knees.

Let go of any agenda concerning how far you stretch forward. Then begin to sense and feel your breath entering and leaving your body. Feel the way the breathing expands and condenses the whole body. Notice that there are brief moments in between the expanding and condensing during which the body and the breath are still. These pauses are rather like the pause of the pendulum when it reaches its arc in space before continuing its trajectory to the other side. From stillness the breath expands and moves you, and as it condenses it moves you, returning back to the ground of stillness before beginning the cycle again.

Imagine your bones are like tiny, light boats bobbing up and down on the current of your breathing. As you give yourself over to this current you find that your body becomes married to the breath. A thousand tiny shifts, rotations, openings, and closings are happening throughout the entire body. Let yourself ‘be breathed’. Then begin to sense and feel more acutely exactly how you are being moved. Can you feel your spine being alternately lifted and lowered? Can you feel your shoulder blades shifting position? Can you feel your spine changing shape, and if so, how does it change shape when you breathe in and

Let go of any agenda concerning how far you stretch forward. Then begin to sense and feel your breath entering and leaving your body. Feel the way the breathing expands and condenses the whole body. Notice that there are brief moments in between the expanding and condensing during which the body and the breath are still. These pauses are rather like the pause of the pendulum when it reaches its arc in space before continuing its trajectory to the other side. From stillness the breath expands and moves you, and as it condenses it moves you, returning back to the ground of stillness before beginning the cycle again.

out? Are your arms a part of this movement, or do they feel cut off from the central current of the breath? Does your head and neck pulse slightly, nodding up and down with the incoming and outgoing breath? Where do you feel your body in co-participation with the breath, and where do you feel cut off from its influence?

Your body’s natural co-participation with the breath happens when you stop controlling with your will and become willing to be moved. Opening your mouth, relaxing your jaw, and taking a few deep sighs as you breathe out through the mouth may help you to release tension and give yourself over to the process. When you are ready, slowly curl up through your spine, supporting your back by placing your hands on your knees if necessary. As you come up to standing or sitting (if you did the exercise on a chair), take a moment to feel how the breath is continuing to move you.

Imagine your bones are like tiny, light boats bobbing up and down on the current of your breathing. As you give yourself over to this current you find that your body becomes married to the breath. A thousand tiny shifts, rotations, openings, and closings are happening throughout the entire body. Let yourself ‘be breathed’. Then begin to sense and feel more acutely exactly how you are being moved. Can you feel your spine being alternately lifted and lowered? Can you feel your shoulder blades shifting position? Can you feel your spine changing shape, and if so, how does it change shape when you breathe in and out? Are your arms a part of this movement, or do they feel cut off from the central current of the breath? Does your head and neck pulse slightly, nodding up and down with the incoming and outgoing breath? Where do you feel your body in co-participation with the breath, and where do you feel cut off from its influence?

Your body’s natural co-participation with the breath happens when you stop controlling with your will and become willing to be moved. Opening your mouth, relaxing your jaw, and taking a few deep sighs as you breathe out through the mouth may help you to release tension and give yourself over to the process. When you are ready, slowly curl up through your spine, supporting your back by placing your hands on your knees if necessary. As you come up to standing or sitting (if you did the exercise on a chair), take a moment to feel how the breath is continuing to move you.

Second Inquiry: Amplifying the Breath

This inquiry is to help you feel more clearly the marriage between breathing and movement. Begin by sitting comfortably in a chair. Place your hands on your thighs with your palms facing forward; gently stretch the hands so the fingers are softly extended but not tense. Then relax the hands and let the fingers curl inward so your palms form a slight hollow. In this way continue rhythmically to fold and unfold the hands for several minutes. Then begin to observe your breath. Do you notice any relationship between the movement of your hands and when you inhale and exhale? Now extend this movement so that you open and turn out your arms and then relax and turn your arms inward. Let the movement expand into your chest so that your chest opens as you gently extend the arms and so that it settles and folds inward as you turn the arms inward. Let your entire spine come into the movement so that the whole body opens and closes like a sea anemone. Observe again how your breath is moving in response to the movement of the body. Let the movement get large and expansive. Feel how the breath changes as the movements grow larger, and then gradually over a period of minutes let the movements become smaller and smaller until you are quiet and still. As you cease the larger physical movements of the body and become quiet, can you still feel the echo of the movement inside you like a light alternately glowing and dimming? This inquiry is an excellent and simple way to ‘kick-start’ your breathing if it has become shallow or restricted. Even in the most public of places, opening and closing your hands will not draw attention to you. You can utilize it in a variety of forms during asana practice by slowly exaggerating folding and unfolding movements in any part of your body and gradually returning to relative stillness, listening and allowing the echo of the breath to continue.

Working with Ujjayi

The steps toward integration of body, mind, and breath can be compared to the apprenticeship of a sailor. Before a sailor can guide his boat he must know the nature of the wind and water—their characteristics, rhythms, and cycles. Without knowledge of these natural forces the most advanced and expensive boat in the world would be of little use. Once familiar with wind and water, the sailor can raise his sails and skillfully guide the boat where he wishes to go. No matter how masterful he is, however, he still cannot control the wind and water—he can only harness them. When you have established a felt sense of your breathing and you are allowing it to move freely, you are ready to move to the next stage of mastery: guiding the breath. Instead of canvas and spinnakers you have the natural opening of your throat and sail-like folds of your vocal cords. Called ujjayi, or the Powerful Breath, this basic pranayama technique involves a very slight closure of the vocal cords, or glottis, at the base of the throat. When done sensitively, your breathing will sound like the echo of the ocean inside a seashell—a deep but soft ‘sssss’ on inhalation and ‘hmmmm’ on exhalation. With ujjayi you can guide breath into the body in a fine, even spray that is deeply soothing to both the lungs and nervous system. The sound of ujjayi gives the mind a more tangible way to adhere to the breath’s movements. With ujjayi you can spread the breath and direct it so that it permeates every cell of the body. All of the principles of moving with the breath still apply, only now you are guiding and refining these movements of the breath for your own benefit. My experience with ujjayi is that it begins to happen naturally during the practice of asanas, and should never be forced or done so loudly that someone across the room can hear it. If you have a tendency to hold your breath and are only just beginning to feel your body moving in synchrony with your breath, I suggest you leave ujjayi alone. If you attempt to practice it too soon you will only be overlaying ujjayi upon your preexisting tension patterns and breath-holding habits. Take the time to explore the previous inquiries until you feel connected to your natural breath.

Third Inquiry: Guiding the Breath

Practice a simple posture that you know already, or if you are new to Yoga, try this inquiry in your chair. First, connect with the natural rhythm of your inhalation and exhalation and the movements in your body that correspond to these two phases of the breath. Then begin to practice ujjayi, feeling how this slight closure of your vocal cords allows you to modulate the volume, quality, and direction of the breath, much like using a nozzle on the end of a garden hose. Notice any changes in how you experience the posture. See the form of the posture in your mind’s eye, and direct the breath so that it is moving in synchrony with the natural lines of the movement. Then, more specifically, guide the breath into any areas that feel resistant, tight, or dull, letting the spray-like quality of ujjayi penetrate each and every cell. At any time in your practice you can let go of ujjayi and return to normal breathing. Take a moment as you complete the posture to notice the effect this breathing practice has had on your state of mind.

The Principle in Practice

- Take time to connect with your breath before you begin a movement and then as you practice the asana go slowly enough so that you don’t lose the connection.

- Whenever you notice yourself holding your breath, exhale completely, blowing the air out through your mouth until the last whisper of air leaves your lungs. Wait for the inhalation to begin spontaneously, and then begin the Yoga asana again with the support of your breath.

- Slow down! Roughness, unevenness, or shortness of breath are signs that you are forcing the body to open too quickly or are moving in a way that is creating disharmony.

Choosing the Present

Our breath is constantly rising and falling, ebbing and flowing, entering and leaving our bodies. Full body breathing is an extraordinary symphony of both powerful and subtle movements that massage our internal organs, oscillate our joints, and alternately tone and release all the muscles in the body. It is full participation in life. By returning over and over again to the essential nature of the breath we can relinquish the fixity of the past and the imagined inevitability of the future, turning back toward the opportunity that awaits us in the next breath. Thus to attune yourself to your breath is to make a decision—perhaps the most radical decision you have ever made. The second you choose to mind your breath you have decided that this present moment, this very moment, is worthy of your full attention. The instant you do this you have begun to extricate yourself from the hold of the past and the pull of the future. You are living your life as a today rather than a yesterday or tomorrow.

This article originally appeared in The Breathing Book by Donna Farhi. Copyright © 2000 by Donna Farhi. Reprinted by arrangement with Henry Holt and Company, LLC. Figures 1-5 are adapted from the book.

It is part of a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana, each followed by New Insights gained from over three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus Feature article, such as this one, will be released.

None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts

Series 2 – Classes 1-4 Bundle

Series 2 – Classes 1-4 Bundle