June 26

by Donna Farhi

Dear Reader

Please keep in mind that the images in this column were scanned from original archived articles and the quality might sometimes vary.

Benefits

Contraindications

Although in the West we’ve come to use the word ‘pose’ as a synonym for ‘asana’, a Yoga asana is not simply a pose. A pose is a static copy of something other than ourselves, but an asana is a movement that arises within us. While an asana may seem static to a casual observer, it is not a fixed position at all. Rather, the form of each asana acts as a container for subtle yet dynamic inner movement. For a dancer or athlete, internal impulses result in movement through space. For a Yogi, these impulses move instead along internal lines of force, reverberating within and constantly renewing the container of the asana. When we witness a practitioner skilled in this dynamic internal dance, we sense a body in continuous, subtle motion. Too often, students interpret and practice ‘asana’ as ‘rigid stance’, perhaps because our images of asanas come from photographs, or because some instructors teach asanas as static sculptures. But if we rely on such guides, we may strive to obtain the external appearance of an asana without ever gaining the true internal experience of it.

Although in the West we’ve come to use the word ‘pose’ as a synonym for ‘asana’, a Yoga asana is not simply a pose. A pose is a static copy of something other than ourselves, but an asana is a movement that arises within us. While an asana may seem static to a casual observer, it is not a fixed position at all. Rather, the form of each asana acts as a container for subtle yet dynamic inner movement. For a dancer or athlete, internal impulses result in movement through space. For a Yogi, these impulses move instead along internal lines of force, reverberating within and constantly renewing the container of the asana. When we witness a practitioner skilled in this dynamic internal dance, we sense a body in continuous, subtle motion. Too often, students interpret and practice ‘asana’ as ‘rigid stance’, perhaps because our images of asanas come from photographs, or because some instructors teach asanas as

static sculptures. But if we rely on such guides, we may strive to obtain the external appearance of an asana without ever gaining the true internal experience of it.

To experience the true fruits of Hatha Yoga practice, we can’t simply copy old forms, mechanically mimicking traditional positions. The original Yogis explored, experimented, and invented new ways to move and be in the body, and we must practice in their spirit-sensing, feeling, and acting from our own internal motivations—if we’re to actively participate in the continuation and evolution of Yoga.

In our modern world, we have many new tools to help us rediscover and extend the path of the original Yogis. My own Yoga explorations have been especially illuminated by the work of Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, director of the School for Body-Mind Centering©. Her theories about the way in which human movement patterns arise, from conception through to

To experience the true fruits of Hatha Yoga practice, we can’t simply copy old forms, mechanically mimicking traditional positions. The original Yogis explored, experimented, and invented new ways to move and be in the body, and we must practice in their spirit-sensing, feeling, and acting from our own internal motivations—if we’re to actively participate in the continuation and evolution of Yoga.

In our modern world, we have many new tools to help us rediscover and extend the path of the original Yogis. My own Yoga explorations have been especially illuminated by the work of Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, director of the School for Body-Mind Centering©. Her theories about the way in which human movement patterns arise, from conception through to adulthood, can provide modern day practitioners of Yoga with a road map for reconnecting with the internal world that makes an asana an organic, living experience rather than just an imitative, static pose.

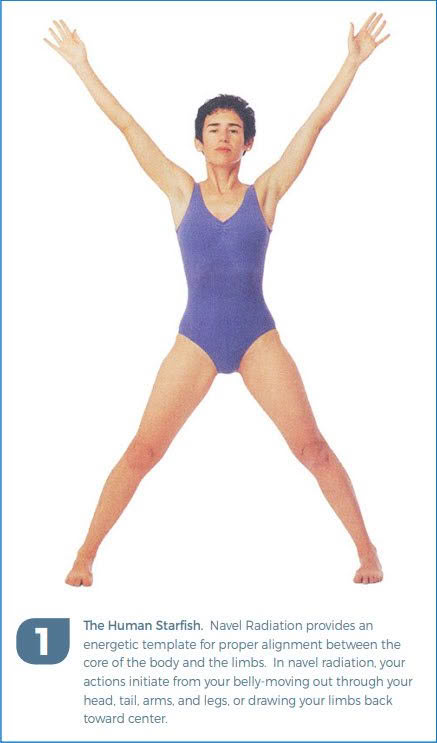

One important movement pattern described by Bainbridge Cohen, Navel Radiation, begins in utero and continues to develop into early infancy. In our mother’s womb, receiving nourishment and eliminating waste through the umbilical cord, we are like a starfish with its sensitive arms extending from and feeding back into its central mouth. Like a starfish, we initiate movement from our center, moving from our core out into our six limbs: two arms, two legs, head, and tail (Fig. 1). These limbs become fluid projections of our core, their relationship to each other organized around the center of the body at the navel.

adulthood, can provide modern day practitioners of Yoga with a road map for reconnecting with the internal world that makes an asana an organic, living experience rather than just an imitative, static pose.

One important movement pattern described by Bainbridge Cohen, Navel Radiation, begins in utero and continues to develop into early infancy. In our mother’s womb, receiving nourishment and eliminating waste through the umbilical cord, we are like a starfish with its sensitive arms extending from and feeding back into its central mouth. Like a starfish, we initiate movement from our center, moving from our core out into our six limbs: two arms, two legs, head, and tail (Fig. 1). These limbs become fluid projections of our core, their relationship to each other organized around the center of the body at the navel.

We may initiate activity from the navel toward the head, the tail, or both simultaneously. We may initiate movement from the navel to one hip, into a leg, or from one arm to the opposite leg, moving through our center in a diagonal line.

In Navel Radiation, movement always flows in waves from the center to the periphery and back again, amplifying an earlier developmental movement pattern the expanding/condensing motion of the breath.

Most adults who consciously engage the movement pattern of Navel Radiation find its fluid ease wonderfully sensual and pleasurable. Many people find that as they release into the infinite possibilities of the pattern, they lose all track of time. In this timeless place, movement happens, and the separation between the doer and the movement ceases. By exploring Navel Radiation, we can discover that we do not need to will ourselves into action: our breath and inner impulses will move us, if we simply allow ourselves to be moved.

Exploring Navel Radiation

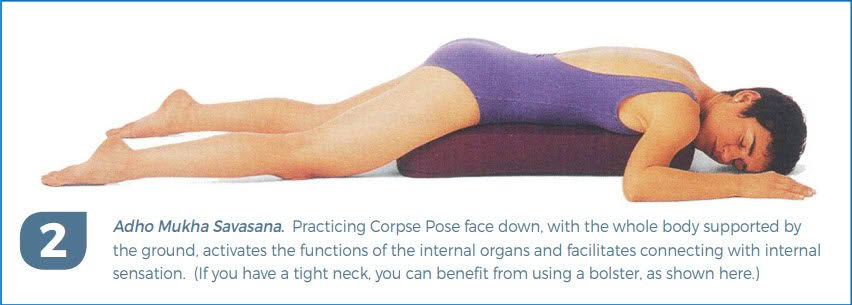

To begin to explore Navel Radiation in your Yoga practice, lie on your belly on a soft surface, allowing your head to turn to one side and your limbs to rest in any configuration you find comfortable. If turning your head is awkward, support your torso from the top of the breastbone to your pubic bone with a bolster, pillow, or stack of folded blankets so that your chest is elevated and your head rests lightly on the ground (Fig. 2). Allow yourself to release your weight into the earth, feeling the tremendous comfort and ease of embracing the ground with your soft front body. Take some time to let yourself settle into the earth and to feel a connection with your breathing. Most important, resist the temptation to direct your movements.

As your breath alternately expands and condenses your body, feel how the belly acts as the central mover. With your attention on your center, notice the impulses that begin there, and track these impulses as they travel through you. You may feel a wave moving from deep in your belly down into your tail, or up your spine into your head. You might notice an impulse from your navel traveling into one hip and leg, or into a shoulder and arm. As you feel these impulses, coparticipate with the movement. Rather than directing your movement by thinking about it, open yourself to feeling the impulses and allowing them to amplify into movement.

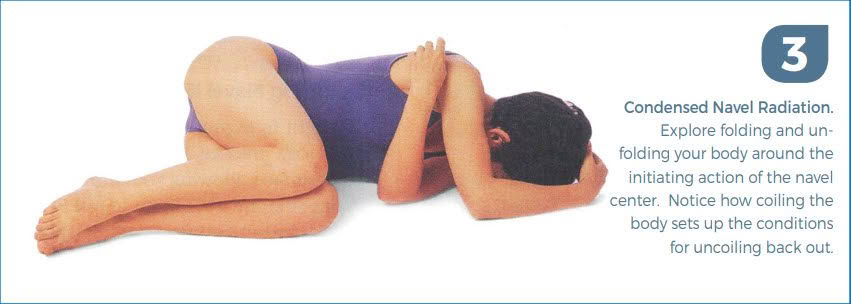

Imagine yourself as a human starfish, with your center of intelligence at the level of your navel, and your sensitive limbs radiating out from there. Begin to explore this concept, first expanding your limbs away from the belly (either individually or in combination), then condensing (feeding your limbs back into the belly). As you expand and condense, allow your belly to initiate the movement, as if your limbs were attached to your center by invisible energetic strings that wind and unwind from your core. Don’t have any preconceived ideas about where your movements may take you. Everyone has their own style of moving in Navel Radiation, just as everyone walks a little differently. One possible expression of Navel Radiation is to curl up like a fetus, limbs coiled in toward your center (Fig. 3). In Navel Radiation coiling inward always sets up the potential for releasing and uncoiling into an opening movement. As you play with the possibilities, feel free to roll onto your back or side, and to change levels (coming up to sit or stand).

Supta Padangusthasana

Every asana needs the support of Navel Radiation at its foundation. This pattern organizes the body as an organic, harmonious whole, rather than a collection of disparate parts. Unfortunately, we can easily get so caught up in the details of an asana that we lose track of the matrix that holds those details together so beautifully. Sometimes we get overwhelmed when a teacher deluges us with separate instructions for each part of the body; sometimes we focus too single-mindedlyfeedback on particular actions within an asana. Often, we deaden our internal impulses by rigidly trying to hold the outer form of a Yoga pose.

To avoid these pitfalls and maintain contact with the integrating power of Navel Radiation, let’s try coming into Supta Padangusthasana in an unusual way. Start by lying on your back and curling yourself up like a bug (Fig. 3). Allow all your limbs to feed back towards your center. Then begin to unwind, allowing your limbs to extend in whatever direction feels pleasurable. After a few minutes of folding and unfolding, begin imagining the form of Supta Padangusthasana: one leg extended along the floor and one leg extended in the air. The next time you unwind, find the connection from your core to your six limbs, extending from your center to your head, your tail, your arms, and both legs. Don’t hold the pose, but continue to alternate between folding all the limbs in and extending them out. Experiment with the placement of both the leg on the floor and the leg in the air, and also with the placement of your torso relative to your legs. Each time you extend out, attempt to find the most harmonious relationship possible between your limbs and your core.

I’ve discovered that when I ask students to find a harmonious relationship between all the parts of the body, they usually find an exceedingly good alignment-even if I haven’t given any specific alignment instructions. Because each person’s body structure and proportion is unique, good alignment is necessarily relative. To find harmony, we can’t just imitate an ideal form; instead, we must learn how our individual body works and what it is able to do at this particular moment. Seeking harmony within an asana doesn’t mean avoiding challenges. We may need to stretch in ways that feel uncomfortable to open and release restrictions in our bodies. But using harmony as a touchstone can help prevent us from ignoring the pains that warn us of potential injury.

In contrast, when we’re asked to go as far into an asana as we can, or to mimic an ideal form, we tend to forsake harmony to pursue our idea of perfection. Our concepts about the body can become so precious to us that it becomes difficult to hear what the body is actually saying. We may even injure ourselves in the service of these ideas.

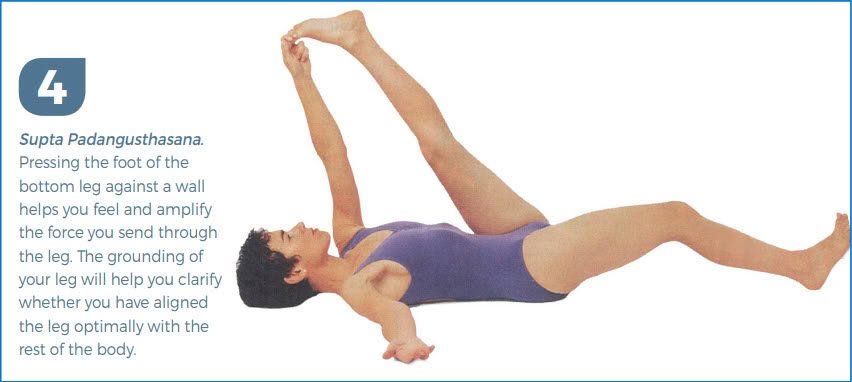

To assist yourself in discovering a harmonious, integrated relationship between all the parts of your body in Supta Pad Angusthasana, place yourself so that the foot of your bottom leg touches the wall while that leg’s knee is still bent (Fig. 4). This time, as you unfurl from your fetal position, press the sole of the foot against the wall. If you have a harmonious connection between your limbs and your trunk, pushing against the wall will send a rebounding impulse up through the leg, into the trunk, and along the spine to the crown of the head. By pressing and releasing your foot against the wall, you can determine if that impulse can move clearly from your leg through your center. When this happens, the force moves strongly through your bones like a train running over well-aligned tracks. When the tracks of your bones are out of alignment, the train of force moving through you can be slowed down, pushed to one side, or stopped altogether.

Experiment with pressing and releasing your foot against the wall until you find the clearest connection between the heel of the foot and the sitting bone on that side. Once you feel the rebounding impulse traveling up your leg and into your pelvis, check that the impulse is allowed to travel into your belly and spine. If the pelvis is overarched, with a big gap between the floor and the lumbar spine, you’ll find that the impulse stops there and goes no farther up your back. Alternately, if you try to flatten your lumbar spine onto the floor, removing the gentle, natural curve, you will also prevent the impulse from your leg from traveling through your core. Continue exploring in this way until you feel a strong connection between your extended leg and your torso, a sense of integration that continues all the way up to the crown of your head.

Now proceed into the classical pose. Start with the left leg extended along the floor and the sole of the foot in contact with the wall. Bend the right knee and draw the leg in towards the chest. Depending on your flexibility, either grasp the big toe with your index and third finger or place a strap around the ball of the foot. As you straighten the leg towards the sky, imagine yourself again as a human starfish, concentrating on keeping open the connections between your core and your limbs. Draw the right leg as close to the chest as you can without losing this sense of connection. Sustain your awareness in this position for a minute or more, and then rest. Before proceeding to the second side, return to the fetal position, and again alternate between expanding outward from your center and condensing back inward, so that you renew your awareness of Navel Radiation.

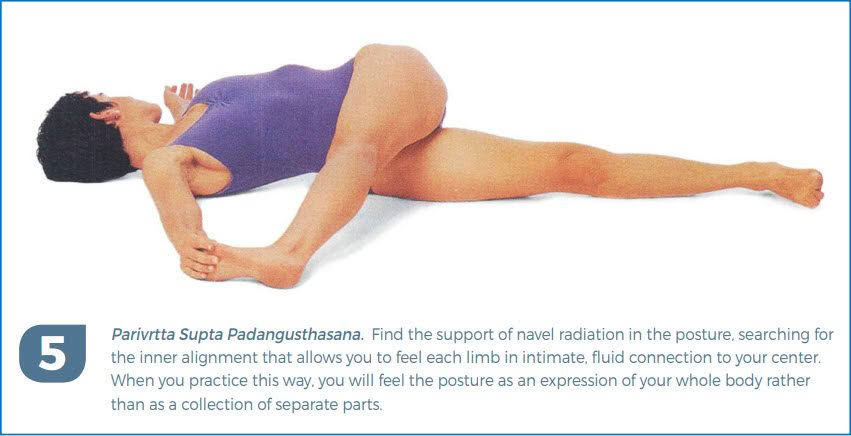

Parivrtta Supta Padangusthanasana

This is one of my all-time-favorite Yoga explorations. Not only does this inquiry feel terrific, it also gives you all the information your body needs to do more advanced variations of Padangusthasana.

Start by lying in a fetal position on your left side, with the sole of your left foot a few feet away from a wall. Relax back into the curvature of your spine. As you rest in this position, visualize the variation of Supta Padangusthasana where the right leg crosses the midline, creating a full-body spiral (Fig. 5). Then slowly begin to unfurl into this position, just as if you were enjoying an early morning stretch in bed. Allow the movement to blossom from your core, with all your limbs simultaneously arriving at their full extension. Alternate three or four times between folding in and opening out, each time exploring where the limbs need to be to maintain the clearest, most harmonious connection to your trunk. With each successive exploration, you can again use the pressure of the foot against the wall to get feedback and clarify your alignment. Keep in mind that the version of the asana shown in Figure 5 is only one possible representation. Though all of our bodies are similar, each of us is also unique, and our asanas should honor this.

Once you’ve found a configuration that feels harmonious, sustain the life of the asana by allowing the body, breath by breath, to release more fully into the movement. Rather than holding the pose rigidly, allow it to change. If you are truly attending to the movements that ripple through you with each breath, you’ll notice an oscillation in every part of your body. For example, a moment of strong extension of your lower leg will be followed by a moment of slight release and retraction. While you should extend your limbs strongly, don’t be so forceful that you prevent this natural oscillation. The breath has a lot to teach you, so listen!

Before you do the asana on the second side, again lie on your back in a fetal position, expanding out and condensing in a few more times. Don’t assume this second side will be the same as the first; you may have to place your limbs very differently in order to find a harmonious position.

Eka Pada Supta Koundinyasana

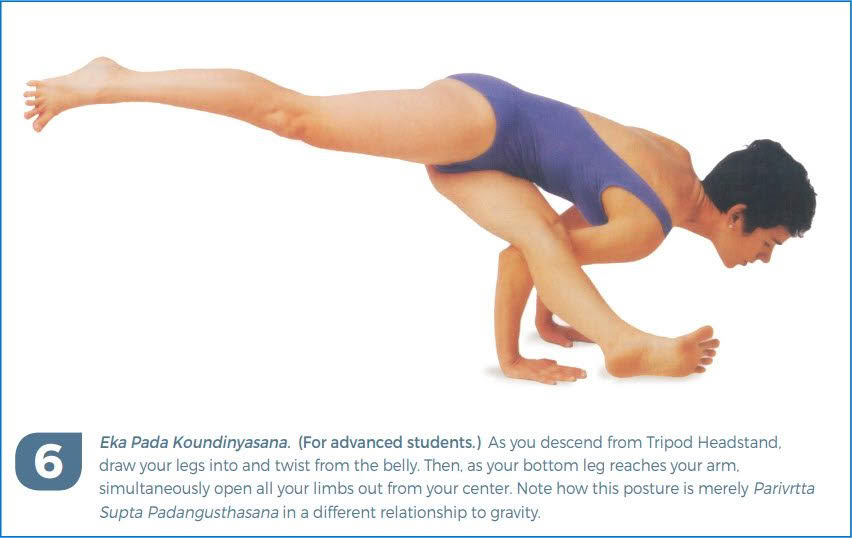

This section discusses advanced asanas, and is for those who have sustained a practice over many years and who are already familiar with the asanas mentioned. Rather than presenting a complete ‘howto’ for these asanas, I will simply suggest ways you can apply the principles studied earlier in the column to such advanced work.

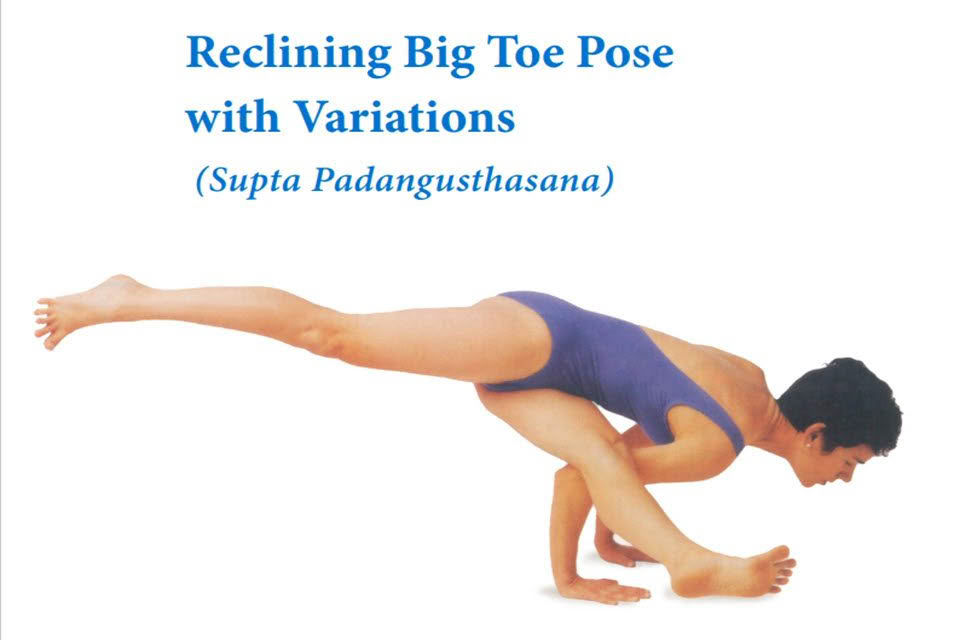

Once you sense how Navel Radiation provides the underlying integration for the twisted variation of Supta Padangusthasana, you can apply your understanding in asanas such as Parivrttaikapada Sirsasana and Eka Pada Koundinyasana (Fig. 6). In fact, both asanas are merely inverted variations of the reclining pose. The added demands of being upside down make engaging the movement pattern of Naval Radiation even more crucial. When you’re coming into Eka Pada Koundinyasana from Sirsasana II, for example, experiment with condensing the legs back towards the navel as you descend, turning the belly at the same time. Then, as you extend your legs, allow all your limbs to radiate out like the limbs of a starfish, with the head, tail, arms, and legs reaching their full extensions simultaneously. If you extend your limbs separately, you will have to adjust and find a new balance each time you bring a limb into place.

Your Body is Wise

Whether you are learning the more basic asanas or practicing complex variations, the underlying principles that govern your movements are the same. As you turn your focus to the supporting matrix of these principles, you may find that many of the details which you previously commanded onto the body now arise spontaneously and joyously from the body. When we drop all our concepts about what we think we know, we find that the information our bodies provide us is greater than the sum of our often self-limiting ideas. If we listen intently to this guiding intelligence, our practice of asana becomes alive and vital, transforming poses into living, breathing creations.

Resources

Sensing, Feeling, and Action by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, (North Atlantic Books, 1994).

The Wisdom of the Body Moving by Linda Hartley, (North Atlantic Books, 1995).

This article originally appeared in Yoga Journal magazine, May/June 1999. Photographs by Bill Reitzel. © 2023 Donna Farhi.

This article is from a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana and will be followed in the next post by an addendum: New Insights. There Donna shares what has changed, since the original article was published, after more than three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus article will be included. None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts

Thank you.

You’re very welcome.