June 3

by Donna Farhi

You'll Need

I used to think of myself as the Queen of arm balances and could easily hold a conversation while balancing in handstand in the center of the room. Having studied intensively for many years with senior teacher and taskmaster Dona Holleman, arm balances were a big part of my weekly practice regimen. Then, seventeen years ago during the tail end of eight-hour computer sessions to bring Yoga Mind, Body and Spirit in on deadline, I began to feel nerve-like twinges in my hands. I foolishly ignored these symptoms, and soon after the manuscript was off to the publisher, instead of resting my hands, I embarked on a series of home repairs which included pick hoeing a driveway, painting a long trellis fence, and finally, scrapping off multiple layers of hardened enamel from the doors and window frames in the derelict property that was then my home. I woke one morning with both hands numb and the peculiar sensation that I had tight rubber bands around each wrist. This was the beginning of what I now refer to as the “hand-less” years. During the ensuing three years, the pain in my hands and wrists made it almost impossible to write with a pencil, lift groceries from a shopping cart onto a counter, to chop vegetables, clean, or even turn the pages of a book. It was a time of great frustration, but also of learning to pay heed to my habit of overdoing, overextending, and overworking.

I used to think of myself as the Queen of arm balances and could easily hold a conversation while balancing in handstand in the center of the room. Having studied intensively for many years with senior teacher and taskmaster Dona Holleman, arm balances were a big part of my weekly practice regimen. Then, seventeen years ago during the tail end of eight-hour computer sessions to bring Yoga Mind, Body and Spirit in on deadline, I began to feel nerve-like twinges in my hands. I foolishly ignored these symptoms, and soon after the manuscript was off to the publisher, instead of resting my hands, I embarked on a series of home repairs which included pick hoeing a driveway, painting a long trellis fence, and finally, scrapping off multiple layers of hardened enamel from the doors and window frames in the derelict property that was then my home. I woke one morning with both hands numb and the peculiar sensation that I had tight rubber bands around each wrist. This was the beginning of what I now refer to as the “hand-less” years. During the ensuing three years, the pain in my hands and wrists made it almost impossible to write with a pencil, lift groceries from a shopping cart onto a counter, to chop vegetables, clean, or even turn the pages of a book. It was a time of great frustration, but also of learning to pay heed to my

I used to think of myself as the Queen of arm balances and could easily hold a conversation while balancing in handstand in the center of the room. Having studied intensively for many years with senior teacher and taskmaster Dona Holleman, arm balances were a big part of my weekly practice regimen. Then, seventeen years ago during the tail end of eight-hour computer sessions to bring Yoga Mind, Body and Spirit in on deadline, I began to feel nerve-like twinges in my hands. I foolishly ignored these symptoms, and soon after the manuscript was off to the publisher, instead of resting my hands, I embarked on a series of home repairs which included pick hoeing a driveway, painting a long trellis fence, and finally, scrapping off multiple layers of hardened enamel from the doors and window frames in the derelict property that was then my home. I woke one morning with both hands numb and the peculiar sensation that I had tight rubber bands around each wrist. This was the beginning of what I now refer to as the “hand-less” years. During the ensuing three years, the pain in my hands and wrists made it almost impossible to write with a pencil, lift groceries from a shopping cart onto a counter, to chop vegetables, clean, or even turn the pages of a book. It was a time of great frustration, but also of learning to pay heed to my habit of overdoing, overextending, and overworking. My hands were having the last say, and as the healing process proceeded at a glacial pace I developed many strategies, techniques, and approaches to gradually heal my wrists. I would never take my hands for granted ever again. As a result of the bi-lateral damage to the ligaments in my hands and the mild arthritic changes to the joints, I am no longer able to practice handstand nor able to descend into Four-Limbed Stick Pose (Chaturanga Dandasana) without adjusting my hands to reduce the angle of extension. These adaptations seem like a small price to pay for having hands that allow me to groom and ride my horses, enjoy the pleasures of the vegetable garden, and to chop, slice, and dice to my heart’s content. My hands were having the last say, and as the healing process proceeded at a glacial pace I developed many strategies, techniques, and approaches to gradually heal my wrists. I would never take my hands for granted ever again. As a result of the bi-lateral damage to the ligaments in my hands and the mild arthritic changes to the joints, I am no longer able to practice handstand nor able to descend into Four-Limbed Stick Pose (Chaturanga Dandasana) without adjusting my hands to reduce the angle of extension. These adaptations seem like a small price to pay for having hands that allow me to groom and ride my horses, enjoy the pleasures of the vegetable garden, and to chop, slice, and dice to my heart’s content.

My hands were having the last say, and as the healing process proceeded at a glacial pace I developed many strategies, techniques, and approaches to gradually heal my wrists. I would never take my hands for granted ever again. As a result of the bi-lateral damage to the ligaments in my hands and the mild arthritic changes to the joints, I am no longer able to practice handstand nor able to descend into Four-Limbed Stick Pose (Chaturanga Dandasana) without adjusting my hands to reduce the angle of extension. These adaptations seem like a small price to pay for having hands that allow me to groom and ride my horses, enjoy the pleasures of the vegetable garden, and to chop, slice, and dice to my heart’s content.

habit of overdoing, overextending, and overworking. My hands were having the last say, and as the healing process proceeded at a glacial pace I developed many strategies, techniques, and approaches to gradually heal my wrists. I would never take my hands for granted ever again. As a result of the bi-lateral damage to the ligaments in my hands and the mild arthritic changes to the joints, I am no longer able to practice handstand nor able to descend into Four-Limbed Stick Pose (Chaturanga Dandasana) without adjusting my hands to reduce the angle of extension. These adaptations seem like a small price to pay for having hands that allow me to groom and ride my horses, enjoy the pleasures of the vegetable garden, and to chop, slice, and dice to my heart’s content.

Currently in my travels, I am encountering many students with similar wrist injuries, which, in the absence of challenges such as pick hoeing driveways, seem to be the result of excessive repetition of practices such as the Sun Salutation (Suryanamaskar), and ambitious pursuit of the latest yoga status symbol, extreme arm balances. Frankly, many of these arm balances makes my own modest column here appear terribly pedestrian. Although I can appreciate the dedication, focus, and sheer physical conditioning required to stand on one hand or to put one foot behind your head while in Crane Pose, an excessive focus on such practices may have long-term consequences for your wrists. Take heed or bear the consequences.

The following adaptations and exercises can be practiced in Downward Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana), and can be gradually incorporated into more difficult weight-bearing positions. You will need a wrist wedge for these practices. First, a note about hard foam wrist wedges. The angle of most foam wrist wedges is not adjustable which means that as your wrist extension improves you will be unable to decrease the incline of the support. Furthermore, the surface of many of these wedges can be dangerously slippery, and I’ve seen enough people lurch abruptly on wedges not to use them. Instead, invest in making yourself a simple wrist board, which will give you a supportive adhesive support. Whatever you put under the base of your hand should not yield to the pressure of your body weight (which is the reason you should never practice weight-bearing postures on soft carpet, sand, or other yielding surfaces if you want a future that includes healthy hands).

How

Variation A: Self-Supported Wrists, Elbows, and Shoulders

Wrist problems often arise because of excessive extension not only at the wrist, but also in the elbows, shoulders, and through the spinal column. It’s a common kinesthetic hallucination for people to feel that pressing the spine and shoulders downwards lengthens the back, when in fact hyperextension of the spine and shoulder joints serves to radically compress the posterior joint surfaces while momentarily opening the anterior joint surfaces. Compression of the wrists may simply be the symptom of a more generalized tendency to collapse in an effort to increase flexibility.

As the body weight sinks into the spine, shoulders, and elbows, the weight tends to fall into the base of the wrist. The palms will tend to contract and the fingers will lift away from the ground. To correct this tendency, and to relearn how to engage sufficient support through the shoulder girdle and arms, place a rolled-up blanket or slender bolster under the base of the forearm close to the wrist. Begin in an all-fours position. As you press back through the hands and lift up to assume Downward Facing Dog, lift your forearms up and away from the bolster (Fig. 15).

Even as you deepen into the posture, can you do so without touching the bolster? This will teach you how to engage your forearm muscles, keep the wrist joints stable, and move the weight forward into the base of the fingers and equally into the surface area of each finger. You can also work with a partner. Have your partner press firmly on the tops of your forearms. Press up against this pressure to engage the forearm muscles and reduce the amount of weight coming into the base of the wrist (Fig. 16).

Variation B: Using a Wrist Wedge

Many of my older students who have mild arthritic changes in their hands need a wrist wedge to comfortably practice postures on all-fours such as Cat Pose. Although rolling under the edge of the yoga mat and raising the base of the wrists can be an expedient solution, yoga mats tend to yield to weight and therefore offer limited support for already compressed and compromised joints. Instead, roll back your yoga mat and place the wrist board on top; the lifted side will be close to you with the opposite edge of the board on the floor. Depending on the degree of your movement limitation, begin with quite a large roll under the wrist board. If you are tall and need the entire length of your mat, you may wish to use a second yoga mat as a roll under your wedge. Experiment with the position of your hand on the edge of the board relative to the floor. For conditions such as carpel tunnel syndrome (caused by pressure on the median nerve), you may need to practice Downward Facing Dog with an essentially neutral position of the wrist relative to the arm (Fig. 17).

As your wrist extension improves, you can decrease the size of the roll under the board so that you are working with more extension (Fig. 18). Issues with the wrists take time to heal, so be willing to work very gradually over a period of weeks and months before you attempt to work without the wrist wedge.

Variation C: Modified Hand Position for Upward Facing Dog Pose (Urdhva Mukha Scanasana)

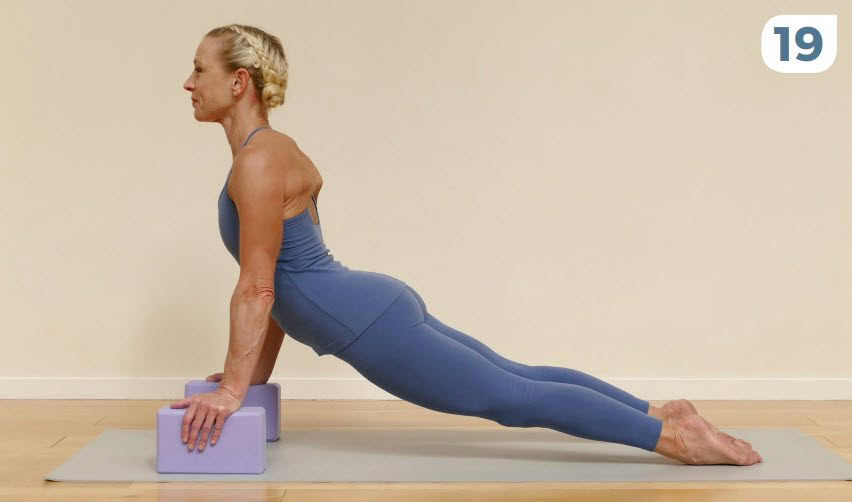

People tend to be very inventive when finding alternative hand positions for postures like Upward Dog Pose (Fig. 14) and East-Facing Pose (Fig. 10). Some options include wrapping the hands around a yoga block so that the wrist is in a relatively neutral position (Fig. 19).

Although I have seen many people support themselves on clenched fists, this looks quite brutal and uncomfortable to my eyes. My personal preference is to assume a ‘chicken claw’ position with my fingers turned back towards my feet, thumbs extended, and the wrists in an absolutely neutral position (Fig. 20). Certainly, if it doesn’t feel comfortable to you, don’t do it.

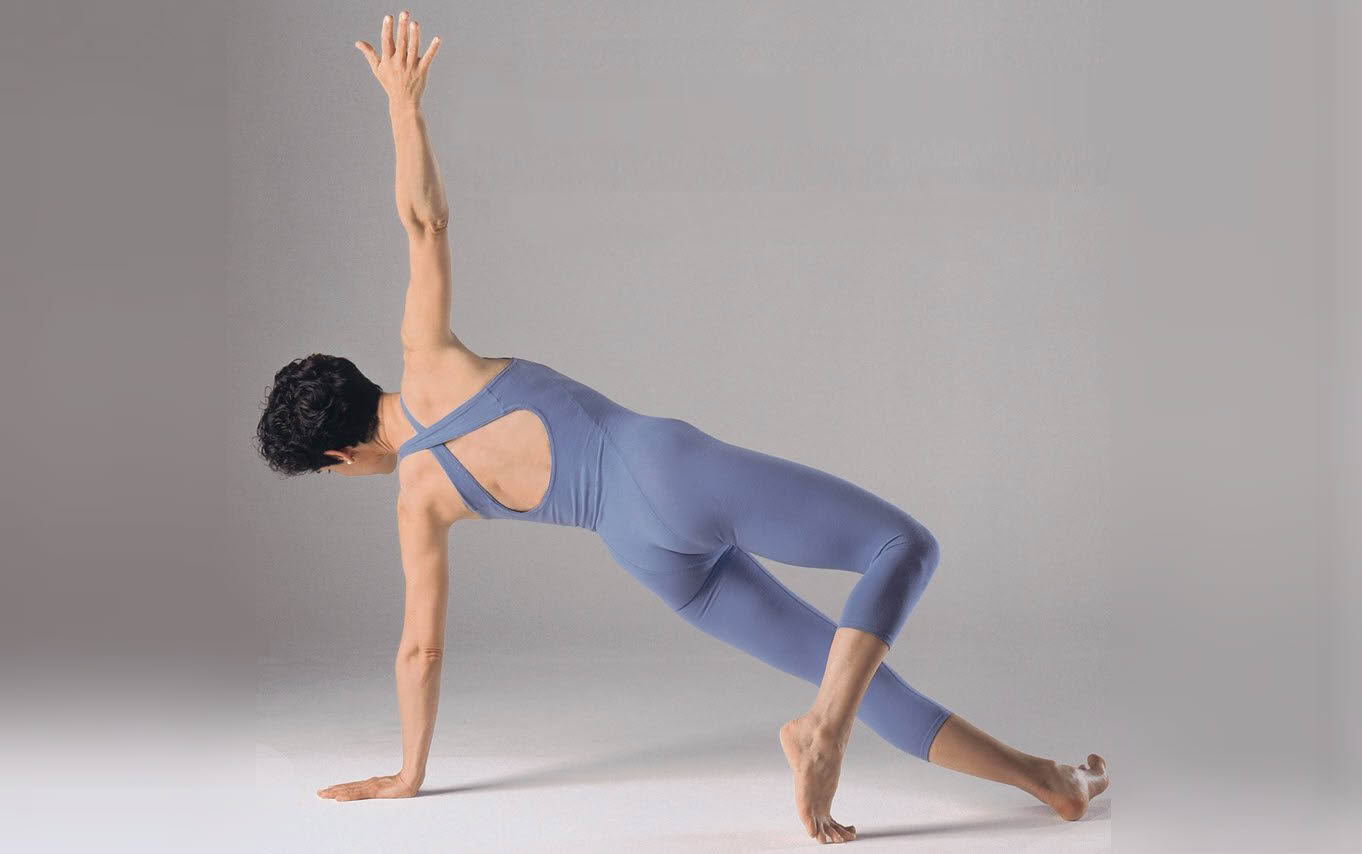

Series of The Arm Balance Sequence (Vasisthasana) with Donna Farhi and her colleague

Variation D: Safe Transitions within the Sun Salutation Suryanamaskar

Even if your arms are very strong, if you have limited extension in your wrist joints due to injury or arthritic wear, it can be painful and counterproductive to descend into Chaturanga Dandasana from a Plank Position, or to move from Downward Facing Dog into Chaturanga Dandasana with straight legs. Plank Position is particularly bad for people with wrist issues because the full body weight is coming onto the wrist while it is extended. If you bend your elbows as soon as you begin your transition from Downward Facing Dog, there is significantly less pressure into the wrist. Many people find it more comfortable to transition from Downward Facing Dog by first lightly resting the knees on the floor (Fig. 21), then moving forward into Chaturanga Dandasana (Fig. 22), and finally straightening the legs and lifting the knees off of the floor (Fig. 23).

Another approach for those with both wrist and lower back issues is to wrap the hands around the seat of a chair (Fig. 24). One can practice Downward Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) and Upwards Facing Dog (Urdhva Mukha Svanasana) (Fig. 25).

If you are practicing these modifications within a Yoga class, never feel that you are inferior to your classmates. Your willingness to skilfully work with your limitations and to practice non-violence towards yourself, is a sign of inner advancement toward the deeper truths of Yoga.

This article supplements the original post released two days ago. It was first published between 1988 and 2003 when Donna was writing full-length feature articles for Yoga Journal and Yoga International USA.

The re-curated originals will be followed by New Insights such as this post, where Donna shares what's changed after more than three decades of teaching internationally. This material is being offered for free for the first time as a service during Donna's sabbatical. All material © 2023 Donna Farhi.

Thanks to Julieanne Moore for her patience and dedicated work as our model.

An occasional bonus Feature article will also be published.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

We'd love to hear your thoughts, so please add any questions or comments below.

share this

Related Posts