May 8

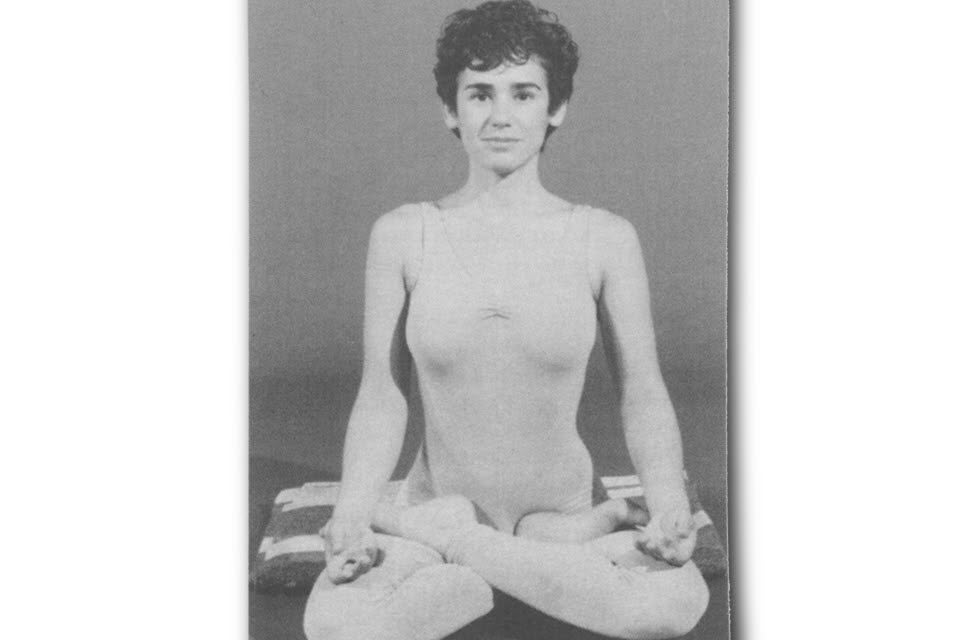

by Donna Farhi

As students, we expect a great deal from our teachers. We expect them to be enthusiastic. We expect them to be reliable. We may even have expectations that they be endless repositories of skill and knowledge from which we may partake at will.

A Zen master invited one of his students over to his house for afternoon tea. After a brief discussion, the teacher poured tea into the student’s cup and continued to pour until the cup was overflowing.

Finally, the student said, “Master, you must stop pouring; the tea is overflowing—it’s not going into the cup.”

“That’s very observant of you,” the teacher replied. “And the same is true with you. If you are to receive any of my teachings, you must first empty out what you have in your mental cup.”

As a teacher, I have come to feel weighted by these expectations and have begun to see that it is really not possible to teach. All the words and theories and techniques are of no use to students who have yet to open themselves with receptivity and to take it upon themselves to practice. So in a sense, I have given up trying to ‘teach’, for I’ve come to believe that the greatest thing I can offer my students is to help them learn how to find themselves through their own investigation.

Many factors come together to make a fine student. Find someone you think is extraordinary, and you will find many, if not all, of the following qualities. People who learn a great deal in what seems like a very short time embody these qualities.

Curiosity

Such people are tremendously curious. The whole world is of interest to them, and they observe what others do not. Nobel Prize-winning physician Albert Szent-Gyorgyi put it well when he said, “Discovery consists of looking at the same thing as everyone else and thinking something different.” 1 With this curiosity comes an ‘investigative spirit’; the learning is not so much the acquisition of information as it is an investigation—a questioning, a turning over of the object of study to see all sides and facets. It is not knowing in the sense of having a rigid opinion, but the ability to look again at another time, in a different light, as Gyorgyi suggests, and to form a new understanding based on that observation.

One way to develop curiosity is to cultivate ‘disbelief’. By disbelieving what we often take for granted, we begin to investigate and explore on our own. In the process, we stop mindlessly parroting our teachers and begin to find how their understanding works in our own experience. Disbelief can be a major step toward creative exploration. In my own classes, I encourage students to investigate, to question my instructions in their own practice. “How does this movement affect my body? What happens if I do it another way? How am I reacting to this posture?” The mere act of saying, “What if...?” opens a completely new dimension of thought. This kind of questioning has led to some of the most exciting inventions of our time.

Discipline

Any discipline—but especially those with great subtlety and complexity, like Yoga or t’ai chi—can be a lifelong pursuit. Persistence, consistency, and discipline are required. Without these, our learning is but froth without substance. There are no shortcuts. The fruit of these seemingly dry qualities (which we prefer to admire in others) is the satisfaction of having tasted the fullness of completion, or the thrill of meeting a difficult challenge with success. Perhaps, though, our culture is in need of redefining what it means to study. If we can look at our chosen discipline or craft as an ongoing process rather than as a discrete accomplishment, the potential for learning can be infinite. With this attitude, we may find ourselves treating even the most mundane discovery with wide-eyed wonder and joy.

Almost anyone can recognize when another’s understanding has true substance. The admiration we bestow on great dancers, musicians, and artists comes from our sense that these people have stepped into the unknown. When we see something extraordinary, we sense the unexpressed third dimension of our own two-dimensional, limited selves. When we take it upon ourselves to step into the unknown, we stop asking our teachers to give our lives meaning and start asking how we ourselves can bring meaning to all aspects of our lives.

Risk Taking

Why is it, then, that so few people live up to their true potential? Beyond the well-paved roads and secure structures we usually build for ourselves lie demons, unsure footing—and unfelt pleasures. To be a student is to take risks. Yet most education discourages people from venturing far enough to take risks or make mistakes. “Children enter school as question marks and leave as periods,” observes educator Neil Postman. What kind of punctuation mark do you represent? Do you find yourself looking for tidy answers that give you a feeling of security? By learning to find the one right answer, we may have relinquished our ability to find other answers and solutions. We learn, then, not to put ourselves into situations where we might fail, because failure has tremendous social stigma. When we try different approaches and do things that have no precedence in our experience, we will surely make mistakes. A creative person uses these ‘failures’ as stepping stones.

Initiative

Can we begin, then, to see that our teachers are guides on our journey, but that the journey itself is our own responsibility? There is nothing quite so satisfying as undergoing a difficult process and after long hard work discovering the true nature of that process. It could be as simple as throwing a perfect pot, or as complex as formulating a new theory of physics. The satisfaction we feel will be directly proportional to the amount of work we do by ourselves to achieve our goal. Successful students do not expect to be spoonfed but take their own initiative. Wanting answers from my teacher has often been a way for me to avoid taking the initiative to discover my own answers through my own practice.

Speaking from the other side of the fence, Yoga teacher Dona Holleman helps clarify the teacher’s role in this relationship when she says, “Helping the pupil must come as a reward for long and persistent work on the part of the pupil. It should be spare and rare. The pupil should do all the work himself, and then the occasional slight help comes as a ‘bonus’.” 2

Looking at our own unexplored terrain helps to strengthen weak areas and to nurture latent talent to fruition. One teacher who profoundly influenced how I learn was the famous Russian ballet teacher Mia Slavenska. After a quick, steely glance at my dance technique, she announced that I could forget everything I had ever learned because it would be of no use to me. Then for one year she demanded that I lift my leg no higher than 12 inches off the floor so that I would learn how to ‘move from the right place’; instead of merely showing off with displays of outward form.” When we give up trying to impress the teacher with what we already know and instead humble ourselves to what we do not know, we enter into a learning mode. Mia was rarely impressed by anyone and rarely offered praise, but, when she did, you knew you deserved it! She claimed that it took a good 8 to 10 years to train an excellent dancer, and her prodigies, many of whom entered renowned companies, showed the exceptional brilliance and truth of the combined dedication of teacher and student.Enthusiasm

To learn, then, is to open oneself. Jim Spira, director of the Institute for Educational Therapy in Berkeley, California 3 , asks his students to prepare themselves to learn in this way:

“Drop your prior knowledge . . . [and] attempt to grasp the new framework in its own context. The student complains, ‘But I know what is important.’ If what you know is important then it should be there when you finish the course. If you continually ‘hold onto it’, then you’ll only see what is presented in terms of the old knowledge/framework and never really grow in new ways.

“Drop your self-image . . . [and] become what you are involved with to the fullest. The student says, ‘But what I am is important.’ I reply, ‘Don’t get trapped by what you like and dislike.’ Being willing to go through each activity as fully as possible will expand your potential well beyond your present limitations.”

When I am lucky enough to meet people like Jim Spira, who live life as explorers, I find myself uplifted by their presence. These people, who inspire all of us, seem to have tapped into a limitless supply of enthusiasm. They excite us, they enlighten us, and we want some of whatever it is they have. The Greek word enthousiasmos means ‘infused with the divine’.

We often go to classes because we need the enthusiasm of the teacher to bolster us or push us forward, and then we carry that enthusiasm home with us like a fragile package and often watch it diminish until the next class. But eventually we must find a way to stop resisting our own ‘infusion of the divine’. Advanced students of any discipline are constantly finding new ways to connect with the enthusiastic part of themselves that ‘wants to do’. These are the people who will go beyond replication of their teachers or systems to bring fresh new ideas and an iconoclastic vision to fields that have otherwise become jaded and ingrown.

I do not mean to advocate disrespect or casual regard for teachers. They are great gifts to us, but eventually we must become our own person—and the best teachers will help us move in that direction. By devoting yourself to one teacher, you help that teacher learn how best to help you. At the same time, you can develop trust in your teacher and can begin to understand his or her particular vocabulary.

Contrary to the belief that more is better, studying simultaneously with many different teachers and packing in one workshop after another may not be the best way to learn. Don’t be a teacher or workshop junkie. If you find that you practice little on your own but take many classes and workshops, it may be time to assess how much you are really learning. Only through practice (by yourself) and time can you assimilate new information. Integrate new concepts and ideas into your practice in a meaningful way before stuffing yourself with more information and techniques.

Finally, as we each advance on our own unique journey, let us live each day as beginners. Being ‘advanced’ has its own pitfalls—among them complacency and pushing or forcing. To go deeper may mean to be still, to progress more patiently, or to devote more time to other areas of our lives as yet green and immature. As F. M. Alexander, of the Alexander technique, once said to his students as they strained and labored, “Give up trying too hard, but never give up.” 4

Tips for the Aspiring Student

The information that follows is designed as a guide. Teaching Yoga has changed so much in the nearly four decades since this article was written. While there has been significant change over this time, with major technological advances opening online teaching and other events such as the pandemic, there are some constant principles that remain. Please share in the comments below anything you'd like to add.

• Be attentive. Teachers will usually go out of their way to help a self-motivated and interested student.

• Be seen. If you want the teacher to know that you are serious, sit or stand in the front of the class. Make eye contact and introduce yourself, either before or after class.

• Be on time. Consistent lateness is a sign of disrespect. If you take your teacher’s skills so lightly, why should he or she take you seriously? Missing the beginning of class can also be physically dangerous if you have missed explanations and work meant to prepare you for more difficult movements.

• Be consistent. The quality of any class improves when there is a collective commitment to regular attendance. In this way you can gain a cumulative knowledge and progress at a more rapid pace. On a more practical level, your attendance may be your teacher’s livelihood.

• Listen with your whole body. We have come to treat words like the background noise of a radio. Plant words in the pertinent area of your body so that information can be ‘embodied’.

• Appreciate constructive criticism. Remember why you’re there—to break through restrictive habit patterns and to change. Teachers usually reserve the most scathing criticism for their most promising students.

• Questions can help clarify and enrich both teacher and student if the student’s questions are pertinent. If, on the contrary, the student is asking questions because he or she is late or inattentive, the student is being disrespectful to the teacher and fellow classmates and is consequently lowering the quality of the class. Highly personal questions with little relevance to the subject at hand are best asked after class.

• You have the right to disagree—but you do not always have the right to express it. Sometimes it is appropriate to challenge a teacher. It is unethical, however, to argue with a teacher or to badger a teacher in public. If you thoroughly object to what is being taught, you are free to leave and learn elsewhere.

• Let your teacher know how much you appreciate him or her. Teachers need encouragement like everyone else. Giving them feedback when something has proved particularly beneficial or injurious to you can help them improve the quality of their teaching.

Notes

1. Roger Vaon Oech, A Whack on the Side of the Head (New York: Warner, 1983).

2. Dona Holleman, Centering Down (Firenze, Italy: Tipografia Giuntina, 1981).

3. No longer operating.

4. Michael Gelb, Body Learning (New York: Delilah Books, 1981).

Resources

Richard Feynman, "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman" - Adventures of a Curious Character (New York: Bantam Books, 1985). Hermann Hesse, Beneath the Wheel (New York: Noonday Press, 1969). Jean Houston, The Possible Human: A Course on Extending Your Physical, Mental, and Creative Abilities (Los Angeles: Tarcher, 1982).

This article originally appeared in Yoga Journal Sept./Oct. 1987. Michael Ghelerter © 2023 Donna Farhi.

It is part of a series of in-depth discussions on selected asana, each followed by New Insights gained from over three decades of teaching. An occasional bonus Feature article, such as this one, will be released.

None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts

This article is absolutely right in line with what I’ve discovered and continue to discover in my own learning and teaching. Thanks so much for articulating these insights so excellenty, Donna! You remain an inspiration as a teacher, not just of Yoga, but of learning how to learn.

Thank you Amy, on behalf of Donna.