August 21

by Donna Farhi

Doing Yoga with a sensitive partner can quicken our understanding of postures. And teach us the subtle neglected art of communicating to others through touch.

Dear Reader

Please keep in mind that the images in this column were scanned from original archived articles and the quality might sometimes vary.

Benefits

The underlying philosophy governing safe and beneficial partnerwork is that we must ‘work with’ rather than ‘work on’ each other.

We do great injustice to ourselves and others when we treat the body as an object to be ‘used’ or ‘fixed’.

Over a decade ago, a dance teacher taught me something that made an enormous impact on my later development as a Yoga student and teacher. She was demonstrating how to lift the legs ‘from the correct place’, and even though I could see the demonstration and understand the explanation, I couldn’t seem to do the movement.

My teacher saw my perplexity. “Here,” she said, placing my hand around the muscles of her hip. “Feel how I do it.”

Over a decade ago, a dance teacher taught me something that made an enormous impact on my later development as a Yoga student and teacher. She was demonstrating how to lift the legs ‘from the correct place’, and even though I could see the demonstration and understand the explanation, I couldn’t seem to do the movement.

My teacher saw my perplexity. “Here,” she said, placing my hand around the muscles of her hip. “Feel how I do it.”

As I touched her, I felt her movement being directly, wordlessly communicated to my own nervous system. In that moment, I realized that I learned through my skin, through touch, as other people learned through seeing and hearing. I wondered how many other people also learned best this way but struggled instead to comprehend physical information through senses that were inadequate for perceiving it.

Since then, through my interactions with hundreds of Yoga students and bodywork clients, I’ve realized that in order to communicate physical information, we must speak a language the body understands. In this article, we’ll explore some ways we can deepen our Yoga practice and increase our body awareness by learning to communicate with others through our touch. We’ll look at how doing Yoga with the help of a sensitive partner can quicken our understanding of movement and, in some instances, take us further into poses than we can go on our own. But before we begin, let’s take a moment to consider the method and the medium through which we receive tactile information—touch and the skin.

Considered the ‘mother of all senses’, touch is to human beings as sunlight is to plants—essential to survival and nourishing to growth. Even so, a recent college anatomy text failed to include touch in its chapter on the sense organs. In Western culture, our sense experience has become oriented around seeing and hearing, resulting in a rather one-dimensional, barren experience of the world. We rely heavily on the ‘distance senses’ of sight and hearing and largely taboo the ‘proximity senses’ of taste, smell, and touch, virtually excluding nonverbal communication from our experience.

As Ashley Montagu states in his ground-breaking work Touch: The Human Significance of Skin, “The sense most closely associated with the skin, the sense of touch, is the earliest to develop in the human embryo.” A general law in embryology states that the earlier a function develops, the more fundamental to the organism it is likely to be. Montagu elaborates: “The central nervous system, which has as a principal function keeping the organism informed of what is going on outside it, develops as the in-turned portion of the general surface of the embryonic body. The rest of the surface covering, after the differentiation of the brain, spinal cord, and all the other parts of the central nervous system, becomes the skin and its derivatives hair, nails, and teeth. The nervous system is, then, a buried part of the skin, or alternatively, the skin may be regarded as an exposed portion of the nervous system.” (emphasis mine).

Endowed with an enormous number of sensory receptors capable of perceiving heat, cold, touch, pressure, and pain, the skin has almost half a million sensory fibers that communicate to the central nervous system via the posterior roots of the spinal cord. The skin is rarely, if ever, ‘busy’, which means that it is always free to learn. And the skin can’t shut out communication by closing its eyes or holding its ears shut.

While the potential for using touch as a medium of communication and education is clearly enormous, strong social norms prevent us from doing so. From that first staccato, “Don’t touch!” to our cultural preoccupation with sex (which has largely imprisoned touch in the sexual domain) there is great confusion as to what is healthy, acceptable touch. One point is becoming clear: only by desexualizing touch will we be able to experience its full educational potential. (In my experience, the intention behind the touch is the crucial factor, and the people we touch know our motivation on a visceral level within seconds.)

For many people, being touched in this warm, caring, and completely safe way may be a new experience. Touching each other in the context of Yoga practice gives us an opportunity to move beyond the limited arena to which touch has been largely confined, into a more wholesome relationship with each other and with our tactile senses.

As I touched her, I felt her movement being directly, wordlessly communicated to my own nervous system. In that moment, I realized that I learned through my skin, through touch, as other people learned through seeing and hearing. I wondered how many other people also learned best this way but struggled instead to comprehend physical information through senses that were inadequate for perceiving it.

Since then, through my interactions with hundreds of Yoga students and bodywork clients, I’ve realized that in order to communicate physical information, we must speak a language the body understands. In this article, we’ll explore some ways we can deepen our Yoga practice and increase our body awareness by learning to communicate with others through our touch. We’ll look at how doing Yoga with the help of a sensitive partner can quicken our understanding of movement and, in some instances, take us further into poses than we can go on our own. But before we begin, let’s take a moment to consider the method and the medium through which we receive tactile information—touch and the skin.

Considered the ‘mother of all senses’, touch is to human beings as sunlight is to plants—essential to survival and nourishing to growth. Even so, a recent college anatomy text failed to include touch in its chapter on the sense organs. In Western culture, our sense experience has become oriented around seeing and hearing, resulting in a rather one-dimensional, barren experience of the world. We rely heavily on the ‘distance senses’ of sight and hearing and largely taboo the ‘proximity senses’ of taste, smell, and touch, virtually excluding nonverbal communication from our experience.

As Ashley Montagu states in his ground-breaking work Touch: The Human Significance of Skin, “The sense most closely associated with the skin, the sense of touch, is the earliest to develop in the human embryo.” A general law in embryology states that the earlier a function develops, the more fundamental to the organism it is likely to be. Montagu elaborates: “The central nervous system, which has as a principal function keeping the organism informed of what is going on outside it, develops as the in-turned portion of the general surface of the embryonic body. The rest of the surface covering, after the differentiation of the brain, spinal cord, and all the other parts of the central nervous system, becomes the skin and its derivatives hair, nails, and teeth. The nervous system is, then, a buried part of the skin, or alternatively, the skin may be regarded as an exposed portion of the nervous system.” (emphasis mine).

Endowed with an enormous number of sensory receptors capable of perceiving heat, cold, touch, pressure, and pain, the skin has almost half a million sensory fibers that communicate to the central nervous system via the posterior roots of the spinal cord. The skin is rarely, if ever, ‘busy’, which means that it is always free to learn. And the skin can’t shut out communication by closing its eyes or holding its ears shut.

While the potential for using touch as a medium of communication and education is clearly enormous, strong social norms prevent us from doing so. From that first staccato, “Don’t touch!” to our cultural preoccupation with sex (which has largely imprisoned touch in the sexual domain) there is great confusion as to what is healthy, acceptable touch. One point is becoming clear: only by desexualizing touch will we be able to experience its full educational potential. (In my experience, the intention behind the touch is the crucial factor, and the people we touch know our motivation on a visceral level within seconds.)

For many people, being touched in this warm, caring, and completely safe way may be a new experience. Touching each other in the context of Yoga practice gives us an opportunity to move beyond the limited arena to which touch has been largely confined, into a more wholesome relationship with each other and with our tactile senses.

The Role of Partnerwork

To do partnerwork, each practitioner must have an experiential understanding of the basic Hatha Yoga asanas. (For more information about any pose, refer to Yoga Mind, Body & Spirit, Bringing Yoga to Life: The Everyday Practice of Enlightened Living by Donna Farhi.) If you’re a beginner, you’ll be better off attending regular classes with an experienced teacher. The adjustments your teacher gives you, and the technical information you gather, will be valuable resources if you later wish to practice with another person.

If you would like to work with a friend to improve your Yoga asanas, it’s helpful to meet regularly (once a week is ideal), so you can get to know each other’s strengths and weaknesses. Partnerwork works best when both people are at the same level of ability, but it can also be valuable when one is more experienced than the other. If you’re a teacher, doing partnerwork with another person can be an excellent way to receive some of the adjustments you give your students—it can be quite revealing to experience a dose of your own medicine!

One of the advantages of Yoga practice is that it can be done independently. Partnerwork is not intended to pre-empt this independent exploration and responsibility, but to facilitate the process of understanding. And while the practice of Hatha Yoga is largely solitary, the foundation of all Yoga is the principle of unification, not only with ourselves but with others around us and with our environment. Learning to work with and help each other is a wonderful way to impart the larger message of unification.

The underlying philosophy that governs safe and beneficial partnerwork is that we must ‘work with’ rather than ‘work on’ each other. This nondominant relationship requires the helping partner (whether a teacher or another student) to act as a facilitator, whose job is to suggest and encourage the development of new skills in the other person. When we ‘invite’ someone into a movement, we provide a situation in which the practitioner can elicit his or her own neuromuscular response and can thereby learn a skill that decreases rather than increases dependence upon us.

We can only facilitate successfully if we have established an ongoing, interactive feedback system— through our attitude, our intention, and our willingness to listen to the unique needs of each person. The most anatomically correct adjustments can be useless and even injurious if they are administered without regard for the other person’s ‘educational threshold’, the window between too little and too much stimulation where optimum learning takes place.

These philosophical considerations may seem obvious. However, my experience in working with students and other teachers has shown me that our cultural indoctrination as dominators of nature has been unconsciously internalized, and we tend to treat our bodies, and those of other people, as matter to be manipulated. We do great injustice (and possible injury) to ourselves and others when we treat the body as an object to be ‘used’ or ‘fixed’ with force and aggression. When we respect our own and others’ educational threshold, we are working in such a way that changes can be integrated in harmony with our inner being.

When doing partnerwork, always observe the following basic guidelines:

1. Use safe lifting techniques and body mechanics

When helping another person, always consider the health and safety of your own body. If you have a pre-existing problem (such as a spinal or shoulder injury), you may want to avoid any partnerwork that involves heavy lifting.

Good lifting technique involves keeping the spine in a neutral position (to ensure this, keep the breastbone upright at all times) and using the strength and leverage of the arms and legs for support. To lift effectively, stay close to the weight you’re lifting and avoid bending forward and twisting. Always stand on a non-slippery surface and keep the weight directly in front of you.

In positions that involve weight bearing, work with someone approximately the same height and weight as yourself. Never try to support someone who is too heavy for you. If you feel uncomfortable because of a weight difference, come out of the pose immediately. Adjust your position or find a partner who is closer to your size.

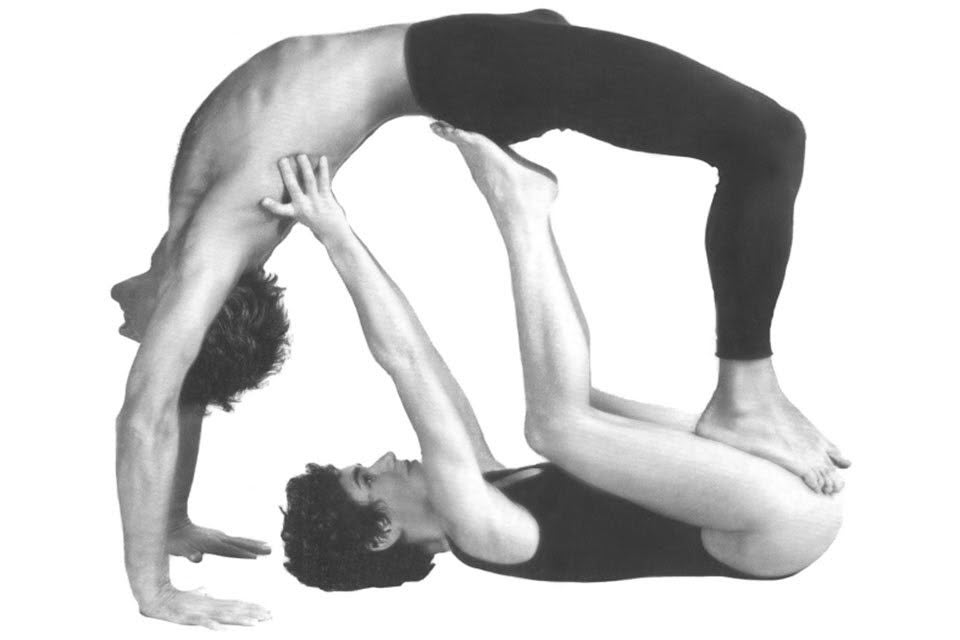

Figure 1 illustrates good lifting technique. The helper brings one foot forward, kneeling on the other knee to keep the spine upright. While lifting, the helper uses the weight of the body to support the load by leaning back, rather than relying on the strength of the arms and legs.

Figure 2 shows a helper lifting incorrectly. The legs are straight, the helper is too far away from the other person, and the lower back is flexed so that the spinal muscles are forced to carry the load. This alignment puts the helper at risk of a serious back injury.

2. Center as the prerequisite to interaction

Be aware that human beings are surrounded by interactive energy fields. Emotions are contagious. The quieter and more centered you are, the more helpful you will be in assisting your partner. To center yourself, contact an inner point of stability, the calm ‘part of yourself that is not identified with the everyday “noisiness” of the mind. Always take a moment to center yourself before you interact. Before you touch your partner, exhale and let superficial and distracting thoughts fall away.

3. Know what you’re doing and why

With your partner, use light pressure until you find the exact hand placement. (If you have no idea how or where to touch your partner, clarify the movement with a teacher rather than confusing your partner by shifting your hands from place to place.) Move slowly and smoothly—rapid or abrupt movements can trigger your partner’s ‘fight or flight’ response. When you’re sure you’re in the best position, gradually increase your pressure, soliciting feedback from your partner. Whenever you give an adjustment that involves rotation, always accompany it with simultaneous traction away from the joint.

4. Be clear about your role

If you’re helping, work ‘with’ your partner, not ‘on’ your partner. Facilitate rather than dominate each interaction. If you’re being helped, be specific in communicating your needs. (For example, say, “Please use less pressure” rather than, “This doesn’t feel right.”) Never be shy about asking your partner to stop.

5. Use the breath as your guide

Synchronize your breath with your partner’s. Most adjustments involving expansion or intensification of a stretch are best done on the exhalation. Encourage your partner to focus on her breathing, so that she can learn how to use the breath to soften dense and immobile areas of the body. You can do this covertly by exhaling with your partner, making an audible ‘ha’ sound. Help your partner increase her exhalation (and subsequent inhalation) by increasing the length of your exhalation.

Never go so deeply or swiftly into a movement that your partner’s breathing becomes disturbed. Tightening the throat, holding the breath, breathing rapidly and shallowly are all signs that the practitioner has been pushed too far. Never intentionally elicit this kind of response. If it occurs, adjust your position or pressure to allow your partner to breathe with ease. You may need to start again and work more slowly and gently.

6. Pay attention!

Focus completely on your interaction. Avoid talking to others or looking away from your partner. Remember, you’re largely responsible for your partner’s safety. Dropping your partner not only undermines trust, but it can lead to serious injury.

7. Avoid undue talking

Excessive talking distances us from our physical experience. People often like to talk about what they’re feeling even before they have allowed themselves to absorb and integrate sensory information. Don’t engage your partner in unrelated conversation. If you need to speak, do so quietly.

8. Finish off

Always let your partner know when you’re going to release your touch or support. Before you do so, encourage your partner to recreate the feeling of the new movement or position on his own. When you do break contact, always move your hands in the direction in which you want your partner to release. Our skins are so sensitive that the movement of air in the wrong direction can send a very confusing message directly into the nervous system.

9. When partnerwork is problematic

You always have the option not to work with a partner, whether because of injury or simple personal preference. Sometimes you may find that your helper (including a teacher) is interacting with you in such an aggressive, invasive, or simply insensitive manner that you fear injury. Or you may feel you’re being touched in a sexually suggestive way (trust your gut instinct about this). Although it may make you feel uncomfortable, let your partner know when you don’t like the way you’re being touched. If necessary, say ‘Yes’ to your ‘No’.

Partnerwork Exercises

There are many reasons to work with another person. For simplicity I have categorized different kinds of partnerwork by objective: education; expansion and intensification; support; sensitization; therapy; and experimentation. There are no hard and fast lines between these categories. All postures and stretches can be adjusted to meet the needs of the individual and the intent of the interaction.

Education

The intention to educate is one of the most powerful and convincing reasons to include partnerwork in a practice session. The challenge of the helper is to provide a situation in which the practitioner can learn to form a new movement on her own. Learning how to relax a tight muscle by consciously breathing into the restricted area, moving force in a particular direction through the body, and sustaining the position of a limb throughout a movement are some of the skills that educational partnerwork can develop.

Almost all partnerwork can be educational if it is done with the active involvement of the practitioner (as opposed to a passive intervention in which the helper simply moves the practitioner into a new position). Partnerwork is only educational if the practitioner is able to replicate the new movement or position on her own, using newfound sensory awareness. This kind of helper-practitioner interaction will initially require more time than a passive intervention, but will be worth it in the long run.

Almost all partnerwork can be educational if it is done with the active involvement of the practitioner (as opposed to a passive intervention in which the helper simply moves the practitioner into a new position). Partnerwork is only educational if the practitioner is able to replicate the new movement or position on her own, using newfound sensory awareness. This kind of helper-practitioner interaction will initially require more time than a passive intervention, but will be worth it in the long run.

Intention

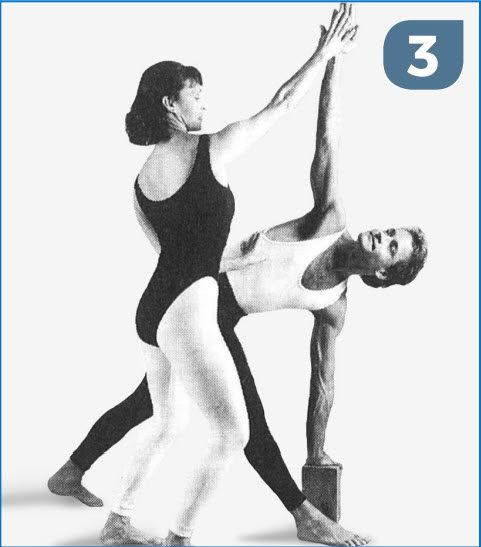

To learn how to integrate the action of the arm in relationship to the rotation of the spine and torso. This adjustment is especially useful for beginners, who often initiate the twist by projecting the arm back behind the chest without turning the torso or spine.

Helper

Once your partner is in Revolved Triangle Pose Parivrtta Trikonasana, place the palm of your hand against the palm of your partner’s upper hand (Fig. 3). Ask her to press strongly against your hand without bringing her wrist behind the plane of

Intention

To learn how to integrate the action of the arm in relationship to the rotation of the spine and torso. This adjustment is especially useful for beginners, who often initiate the twist by projecting the arm back behind the chest without turning the torso or spine.

Helper

Once your partner is in Revolved Triangle Pose Parivrtta Trikonasana, place the palm of your hand against the palm of your partner’s upper hand (Fig. 3). Ask her to press strongly against your hand without bringing her wrist

Almost all partnerwork can be educational if it is done with the active involvement of the practitioner (as opposed to a passive intervention in which the helper simply moves the practitioner into a new position). Partnerwork is only educational if the practitioner is able to replicate the new movement or position on her own, using newfound sensory awareness. This kind of helper-practitioner interaction will initially require more time than a passive intervention, but will be worth it in the long run.

Intention

To learn how to integrate the action of the arm in relationship to the rotation of the spine and torso. This adjustment is especially useful for beginners, who often initiate the twist by projecting the arm back behind the chest without turning the torso or spine.

Helper

Once your partner is in Revolved Triangle Pose Parivrtta Trikonasana, place the palm of your hand against the palm of your partner’s upper hand (Fig. 3). Ask her to press strongly against your hand without bringing her wrist behind the plane

her shoulder. Maintaining this pressure, ask your partner to turn the belly and chest upward on her exhalation. You may want to indicate the correct direction of the rotation by placing your hand gently but firmly on your partner’s lower ribcage.

behind the plane of her shoulder. Maintaining this pressure, ask your partner to turn the belly and chest upward on her exhalation. You may want to indicate the correct direction of the rotation by placing your hand gently but firmly on your partner’s lower ribcage.

of her shoulder. Maintaining this pressure, ask your partner to turn the belly and chest upward on her exhalation. You may want to indicate the correct direction of the rotation by placing your hand gently but firmly on your partner’s lower ribcage.

Practitioner

Press strongly against your partner’s hand without bringing your arm behind the plane of your chest. Keeping your wrist over the head of your shoulder, turn the abdomen, chest, and spine upward on an exhalation. Observe the relationship between the positions of the arm and the torso. Try the pose on the other side without your partner’s help.

Expansion and Intensification

Working with another person can extend your range of motion beyond what is possible (at least initially) on your own, by providing increased leverage or elongation. The helper acts as a kind of animate yoga prop, shifting position based on the practitioner’s moment-to-moment ability to release into the movement.

With its diverse assortment of malleable forms, limbs, convexities, and concavities, the human body is an incomparable yoga prop. Although inanimate props such as wooden blocks, ties, and ropes can be useful (and may be used in combination with a partner stretch), they can’t replace the sensitivity and responsiveness of another human being.

In any interaction that involves increasing range of motion, it is absolutely crucial that the helper work in response to the practitioner’s ability to relax and release into a movement. It isn’t the helper’s job to push the practitioner toward what he thinks the practitioner is capable of. If a person is taken too quickly or forcefully into a movement, an increased range of motion may initially result, but at great risk of injury.

Instead, extending range of motion should be done in an educational way, so that the practitioner learns to evoke his own response to the stretch in order to release and relax. In this way, a practitioner discovers an internal mechanism by which to disengage from his muscular tension and holding patterns. This disengagement from habitual holding patterns is a skill that can bring about deep and often permanent physiological and psychological changes that cannot be attained through force.

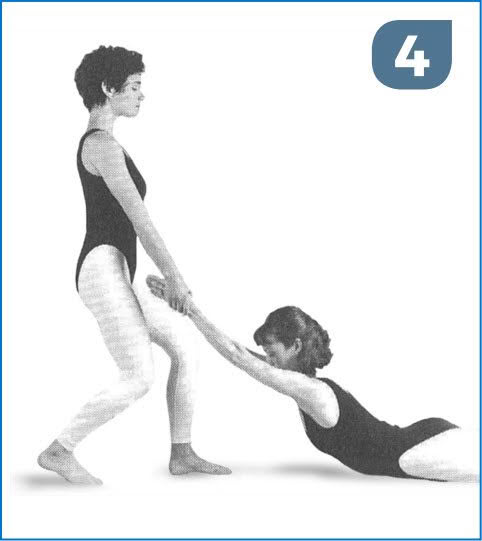

Intention

To provide an intense stretch to the shoulders, spine, and front of the chest and belly. This is also an excellent way to learn to come into backbends while maintaining the length of the front spine.

Helper

Crouch in front of your partner, kneeling on one leg with the other foot forward. (You will start

Intention

To provide an intense stretch to the shoulders, spine, and front of the chest and belly. This is also an excellent way to learn to come into backbends while maintaining the length of the front spine.

Helper

Crouch in front of your partner, kneeling on one leg with the other foot forward. (You will start

Intention

To provide an intense stretch to the shoulders, spine, and front of the chest and belly. This is also an excellent way to learn to come into backbends while maintaining the length of the front spine.

Helper

Crouch in front of your partner, kneeling on one leg with the other foot forward. (You will start in a kneeling position and slowly stand up as your partner goes into the stretch.) Hold your partner’s wrists firmly. Ask your partner to lift his head and chest off the floor on an exhalation, without tightening the back of the neck or raising the chin. Now lift your partner’s arms to the same angle as his torso, always giving slight traction outward by leaning back as you lift (Fig. 4). Continue to ask your partner to lift on each exhalation, lifting his arms each time to keep them in line with his torso.

If your partner is relying too heavily on his posterior spinal muscles, his chin will be raised and the muscles on either side

in a kneeling position and slowly stand up as your partner goes into the stretch.) Hold your partner’s wrists firmly. Ask your partner to lift his head and chest off the floor on an exhalation, without tightening the back of the neck or raising the chin. Now lift your partner’s arms to the same angle as his torso, always giving slight traction outward by leaning back as you lift (Fig. 4). Continue to ask your partner to lift on each exhalation, lifting his arms each time to keep them in line with his torso.

If your partner is relying too heavily on his

Intention

To provide an intense stretch to the shoulders, spine, and front of the chest and belly. This is also an excellent way to learn to come into backbends while maintaining the length of the front spine.

Helper

Crouch in front of your partner, kneeling on one leg with the other foot forward. (You will start in a kneeling position and slowly stand up as your partner goes into the stretch.) Hold your partner’s wrists firmly. Ask your partner to lift his head and chest off the floor on an exhalation, without tightening the back of the neck or raising the chin. Now lift your partner’s arms to the same angle as his torso, always giving slight traction outward by leaning back as you lift (Fig. 4). Continue to ask your partner to lift on each exhalation, lifting his arms each time to keep them in line with his torso.

If your partner is relying too heavily on his posterior spinal muscles, his chin will be raised and the muscles on either side

of his spine will be clenched. Remind your partner to lower his chin and to lift instead from the belly and the breastbone.

posterior spinal muscles, his chin will be raised and the muscles on either side of his spine will be clenched. Remind your partner to lower his chin and to lift instead from the belly and the breastbone.

of his spine will be clenched. Remind your partner to lower his chin and to lift instead from the belly and the breastbone.

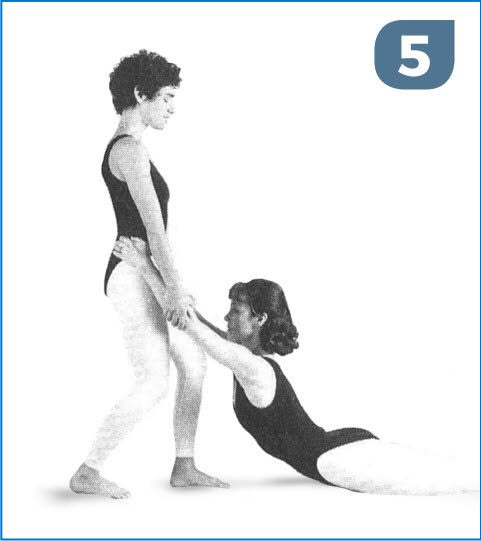

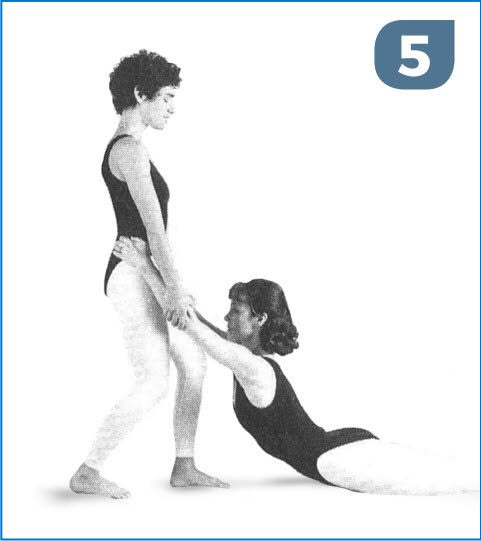

If you’re working with a very flexible student, you may need to walk in and have your partner reach up and hold the back of your pelvis (Fig. 5). As he does this, support his upper arms just above the shoulder joint. Continue to lean back slightly to provide traction. When it is time to lower your partner, protect your own back by kneeling on one knee and bringing your other leg in front of you, keeping your breastbone upright throughout the entire maneuver. Lean strongly away from your partner as you lower him, so his spine remains lengthened.

Practitioner

Extend through your legs and initiate the backbend by lifting the belly and chest up into the front of the spine. Be careful not to raise your chin or overarch your neck, as these actions will cause the back of the spine to contract. Each time you lift up higher, extend your tailbone toward your heel. Instead of clenching the buttocks together, extend your buttocks away from the lumbar spine toward the heels to keep the back long.

If you’re working with a very flexible student, you may need to walk in and have your partner reach up and hold the back of your pelvis (Fig. 5). As he does this, support his upper arms just above the shoulder joint. Continue to lean back slightly to provide traction. When it is time to lower your partner, protect your own back by kneeling on one knee and bringing your other leg in front of you, keeping your breastbone upright throughout the entire maneuver. Lean strongly away from your partner as you lower him, so his spine remains lengthened.

If you’re working with a very flexible student, you may need to walk in and have your partner reach up and hold the back of your pelvis (Fig. 5). As he does this, support his upper arms just above the shoulder joint. Continue to lean back slightly to provide traction. When it is time to lower your partner, protect your own back by kneeling on one knee and bringing your other leg in front of you, keeping your breastbone upright throughout the entire maneuver. Lean strongly away from your partner as you lower him, so his spine remains lengthened.

Practitioner

Extend through your legs and initiate the backbend by lifting the belly and chest up into the front of the spine. Be careful not to raise your chin or overarch your neck, as these actions will cause the back of the spine to contract. Each time you lift up higher, extend your tailbone toward your heel. Instead of clenching the buttocks together, extend your buttocks away from the lumbar spine toward the heels to keep the back long.

Support

Many asanas, especially handstand and other inverted positions, can produce terror in the uninitiated. Fear of falling, fear of injury, or just plain, inexplicable fear can prevent the student from even trying a new asana. To move beyond this fear, partners can help each other by giving support and preventing injury during the initial learning period. This kind of partnerwork might be thought of as Yoga with training wheels.

All partnerwork carries with it the responsibility to be attentive and alert to the moment-by-moment needs of the practitioner. Supportive partnerwork carries with it the additional risk of injury and therefore a greater need for concentration. Both partners should be of similar weight and height, so they can provide support without hurting themselves or their partner. When a student is particularly heavy or stiff, add an extra helper for safety.

Practitioner

Extend through your legs and initiate the backbend by lifting the belly and chest up into the front of the spine. Be careful not to raise your chin or overarch your neck, as these actions will cause the back of the spine to contract. Each time you lift up higher, extend your tailbone toward your heel. Instead of clenching the buttocks together, extend your buttocks away from the lumbar spine toward the heels to keep the back long.

Support

Many asanas, especially handstand and other inverted positions, can produce terror in the uninitiated. Fear of falling, fear of injury, or just plain, inexplicable fear can prevent the student from even trying a new asana. To move beyond this fear, partners can help each other by giving support and preventing injury during the initial learning period. This kind of partnerwork might be thought of as Yoga with training wheels.

All partnerwork carries with it the responsibility to be attentive and alert to the moment-by-moment needs of the practitioner. Supportive partnerwork carries with it the additional risk of injury and therefore a greater need for concentration. Both partners should be of similar weight and height, so they can provide support without hurting themselves or their partner. When a student is particularly heavy or stiff, add an extra helper for safety.

Intention

To prevent the student from collapsing the shoulders and falling on the head during Handstand. This pairing is an excellent way to help strong but stiff or capable but terrified practitioners overcome their fear of coming up into a handstand.

Helpers (two)

Have the practitioner take Downward-Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) with the

Support

Many asanas, especially handstand and other inverted positions, can produce terror in the uninitiated. Fear of falling, fear of injury, or just plain, inexplicable fear can prevent the student from even trying a new asana. To move beyond this fear, partners can help each other by giving support and preventing injury during the initial learning period. This kind of partnerwork might be thought of as Yoga with training wheels.

All partnerwork carries with it the responsibility to be attentive and alert to the moment-by-moment needs of the practitioner. Supportive partnerwork carries with it the additional risk of injury and therefore a greater need for concentration. Both partners should be of similar weight and height, so they can provide support without hurting themselves or their partner. When a student is particularly heavy or stiff, add an extra helper for safety.

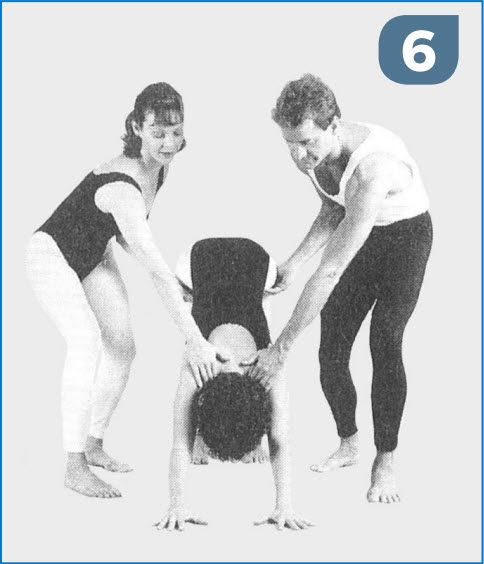

Intention

To prevent the student from collapsing the shoulders and falling on the head during Handstand. This pairing is an excellent way to help strong but stiff or capable but terrified practitioners overcome their fear of coming up into a handstand.

Helpers (two)

Have the practitioner take Downward-Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) with the fingertips 6 to 10 inches from a wall. Stand to either side of the practitioner’s shoulders. If you’re standing on her right side, place your right hand on her right shoulder (the side of the shoulder facing the wall) and your left hand on the lower abdomen just above the right hip. Make sure the other helper is in position before you ask the practitioner to kick up. Holding her shoulder firmly, lift upward with your right hand, and move her pelvis back toward the wall with your left hand. The practitioner should feel completely supported and safe. Do not release your support until she has both legs safely on the floor (Fig. 6).

fingertips 6 to 10 inches from a wall. Stand to either side of the practitioner’s shoulders. If you’re standing on her right side, place your right hand on her right shoulder (the side of the shoulder facing the wall) and your left hand on the lower abdomen just above the right hip. Make sure the other helper is in position before you ask the practitioner to kick up. Holding her shoulder firmly, lift upward with your right hand, and move her pelvis back toward the wall with your left hand. The practitioner should feel completely supported and safe. Do not release your support until she has both legs safely on the floor (Fig. 6).

Intention

To prevent the student from collapsing the shoulders and falling on the head during Handstand. This pairing is an excellent way to help strong but stiff or capable but terrified practitioners overcome their fear of coming up into a handstand.

Helpers (two)

Have the practitioner take Downward-Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) with the fingertips 6 to 10 inches from a wall. Stand to either side of the practitioner’s shoulders. If you’re standing on her right side, place your right hand on her right shoulder (the side of the shoulder facing the wall) and your left hand on the lower abdomen just above the right hip. Make sure the other helper is in position before you ask the practitioner to kick up. Holding her shoulder firmly, lift upward with your right hand, and move her pelvis back toward the wall with your left hand. The practitioner should feel completely supported and safe. Do not release your support until she has both legs safely on the floor (Fig. 6).

Practitioner

Take Downward-Facing Dog about 6 to 10 inches away from the wall. Bring your right leg about a foot forward into a lunge and bend both knees slightly. When your partners give you the signal, spring up, raising the left leg first. (If this feels impossibly awkward, try leading with the other leg.) Arch the neck slightly and look at the floor throughout the entire maneuver. Lift your shoulders away from the support of your helpers’ hands and stretch up through your legs to bring the pelvis vertical. Let your helpers know when you wish to come down. Be conservative—it’s better to come down while you have the control and presence of mind to make a smooth landing. When you do descend, relax your knees and ankles so you land silently, without strain on the joints. Try to remember the feeling of the supported position. If you feel confident, try to come up on your own with your partners standing on either side. . . just in case.

Practitioner

Take Downward-Facing Dog about 6 to 10 inches away from the wall. Bring your right leg about a foot forward into a lunge and bend both knees slightly. When your partners give you the signal, spring up, raising the left leg first. (If this feels impossibly awkward, try leading with the other leg.) Arch the neck slightly and look at the floor throughout the entire maneuver. Lift your shoulders away from the support of your helpers’ hands and stretch up through your legs to bring the pelvis vertical. Let your helpers know when you wish to come down. Be conservative—it’s better to come down while you have the control and presence of mind to make a smooth landing. When you do descend, relax your knees and ankles so you land silently, without strain on the joints. Try to remember the feeling of the supported position. If you feel confident, try to come up on your own with your partners standing on either side. . . just in case.

Practitioner

Take Downward-Facing Dog about 6 to 10 inches away from the wall. Bring your right leg about a foot forward into a lunge and bend both knees slightly. When your partners give you the signal, spring up, raising the left leg first. (If this feels impossibly awkward, try leading with the other leg.) Arch the neck slightly and look at the floor throughout the entire maneuver. Lift your shoulders away from the support of your helpers’ hands and stretch up through your legs to bring the pelvis vertical. Let your helpers know when you wish to come down. Be conservative—it’s better to come down while you have the control and presence of mind to make a smooth landing. When you do descend, relax your knees and ankles so you land silently, without strain on the joints. Try to remember the feeling of the supported position. If you feel confident, try to come up on your own with your partners standing on either side. . . just in case.

Sensitization

All of us have parts of our bodies that lack awareness. Partnerwork can provide excellent biofeedback to bring our attention to an area that has become unresponsive or immobile. These less sensitive, less intelligent regions may result from prolonged stress to a muscle or joint, or a past injury that has resulted in the buildup of scar tissue and adhesions between the muscle fascia. In these ‘numb’ areas the tissue will often feel dense and inelastic, and the muscle and skin may feel glued together. The skin may be discolored, dry and scaly, or marked by acne-all signs of lack of circulation.

A helper can help a practitioner focus on these areas by pressing firmly (with a finger or with the entire hand) and asking the person to ‘breathe into’ the area being touched. I often ask my students to let their body ‘talk to my hand with the breath’, pressing the breath up against my touch on the inhalation and releasing away from my touch on the exhalation. Some parts of the body may not have moved in years, so it is important to stay long enough for the practitioner to retrieve from the nervous system the memory of movement and awareness in that area. Almost without exception, it is not until we can breathe into an area of the body that we can become aware there. It is just as important for the helper to hold her presence and focus upon the area that she is touching as it is for the practitioner to concentrate on bringing his awareness into his body.

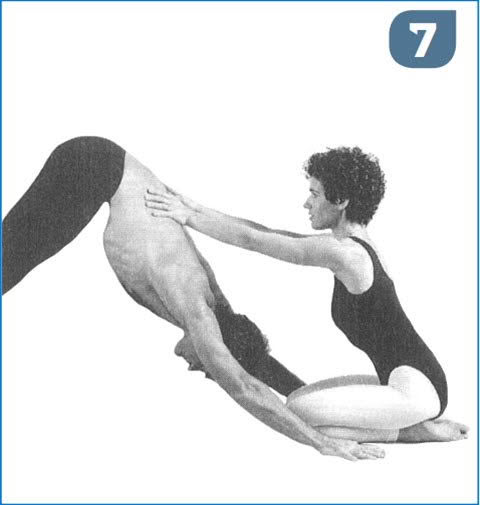

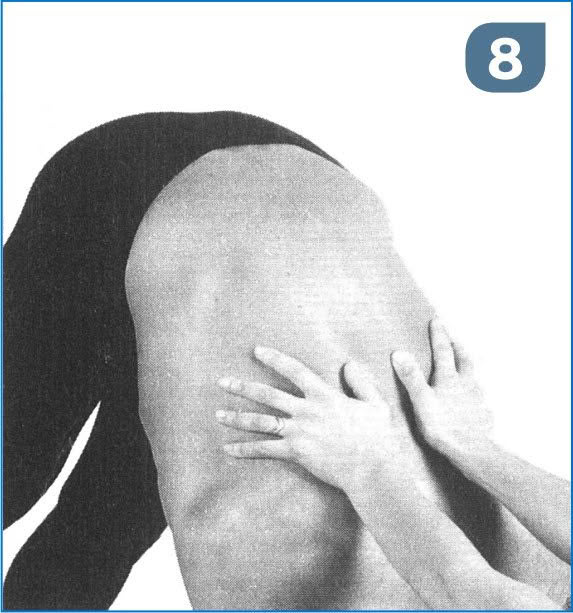

Intention

To increase breath awareness in the spine with an emphasis on differentiating the movement of each vertebral segment.

Helper

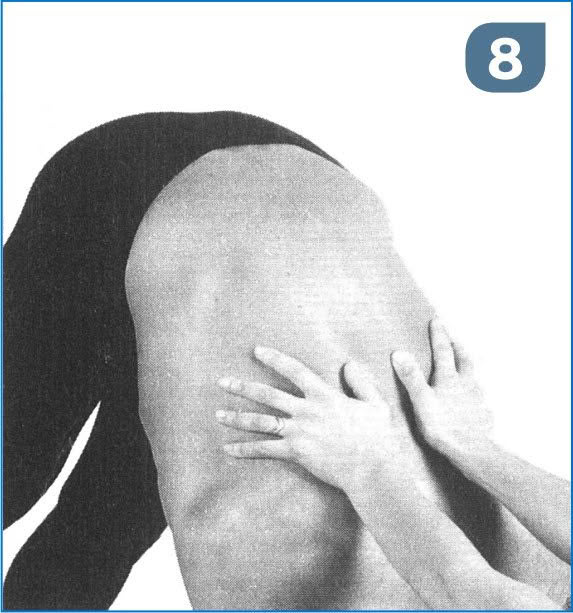

Kneel in front of your partner as he takes Downward-Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana) (Fig. 7). Place your thumbs on either side of his spinal column, level with the upper edge of the shoulder blades (Fig. 8). The pressure through your thumbs should suggest an inward, upward direction, but also a slight movement away from the spinal column. Ask your partner to breath up into the place you’re touching and to release away from your pressure on the exhalation, allowing the spine to softly move into the body.

Move up the back a few inches at a time, staying for longer periods of time where the muscles feel dense and inelastic. Large segments of your partner’s spine may feel stiff and immobile. Let your partner rest halfway through the exercise. Continue all the way up to the sacrum.

Practitioner

Breathe up into the pressure of your partner’s fingers. As you exhale, allow the muscles to soften and release so that the spine slightly indents. When you feel a particularly painful or tight segment of the spine, let your partner know that you want to stay there a while. To bring movement back into these stiff areas, exaggerate both the movement upward against your partner’s pressure and the release downward.

Therapy

Partnerwork can be a powerful tool to alleviate compression or contraction in a particular area of the body. Therapeutic partnerwork often involves providing traction to a single joint, or to the spinal column. However, if a practitioner has an injury or other acute condition, the helping partner should be an experienced teacher who knows the history and nature of the problem.

Intention

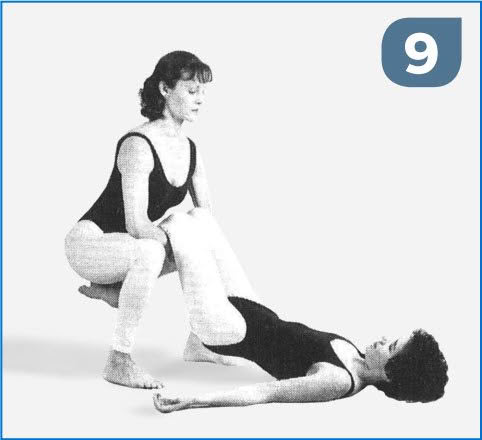

To give gentle traction to the hips and lower back. This technique is excellent for relieving compression in the hips and spine and for releasing muscular spasms.

Helper

This adjustment involves lifting the entire weight of your partner’s legs and torso off the floor. (Do not attempt the adjustment if your own back is injured, or if your partner is too heavy to make safe lifting possible.) Stand facing your partner, bending from the knees as you lift her legs. Create a bridge with your arms behind her knees at the top of the calf muscle, by holding your left elbow with the right hand and vice versa. Support your elbows on your knees as you lean back and lift your partner’s legs and pelvis off the ground. Continue to lean back to give your partner a deep, prolonged release in the hips and back. Keep your own knees bent and your chest upright to protect your back (Fig. 9). Lower your partner slowly to the floor, continuing traction throughout the entire maneuver.

Helper

This adjustment involves lifting the entire weight of your partner’s legs and torso off the floor. (Do not attempt the adjustment if your own back is injured, or if your partner is too heavy to make safe lifting possible.) Stand facing your partner, bending from the knees as you lift her legs. Create a bridge with your arms behind her knees at the top of the calf muscle, by holding your left elbow with the right hand and vice versa. Support your

Practitioner

Relax your legs and torso completely. If you try to ‘help’ your partner, you may strain his back. As you exhale, give your helper the full weight of your body. Focus on softening and releasing the muscles in your hips, buttocks, and lumbar spine. Let your partner know if you feel discomfort at any time. When you come out of the stretch, take a moment to feel the sensation in your body. Can you recreate this feeling of length during your working day and your Yoga practice?

Experimentation

Last but not least, working with a partner can be a joyous way to bring fun and spontaneity into a practice session. New and beneficial partnerwork scenarios often arise out of this kind of playfulness. When I practice with a close friend, we often discover new ways to access tight areas of the body through open-minded experimentation. Giving our imaginations a little freedom is a great way to bring lightness into both our movements and minds.

Partnerwork scenarios come as a solution to problems, difficulties or limitations. I’ll often ask a friend for help in getting more efficient leverage in an advanced asana, or to spot me when attempting a pose where I might otherwise fall on my first attempt. Or we may start with a paired stretch and find that we improvise to accommodate one person’s physical limitation or flexibility, creating something completely new.

Often, very flexible areas of the body are surrounded by immobile areas. It may be difficult to begin to move the rigid parts of the body, because we will naturally move from where we are already flexible. A partner stretch may help to stabilize a flexible region, so we can explore a tighter one.

Ask yourself where you feel restriction in difficult postures and work with your partner to devise ways to access those areas. (You can draw on adjustments that you have found particularly helpful in Yoga class.) Experimenting involves communicating with your partner. For example, you might say, “I feel like my shoulders are collapsing in this backbend. Could you help by lifting under the shoulder blades?” As your partner makes the adjustment, keep the dialogue going: “If you move your hands lower (or higher) it will give me more support,” or, “That’s too much (or too little) pressure.” These kinds of statements can clarify how you help and are helped by your partner.

elbows on your knees as you lean back and lift your partner’s legs and pelvis off the ground. Continue to lean back to give your partner a deep, prolonged release in the hips and back. Keep your own knees bent and your chest upright to protect your back (Fig. 9). Lower your partner slowly to the floor, continuing traction throughout the entire maneuver.

Practitioner

Relax your legs and torso completely. If you try to ‘help’ your partner, you may strain his back. As you exhale, give your helper the full weight of your body.

Focus on softening and releasing the muscles in your hips, buttocks, and lumbar spine. Let your partner know if you feel discomfort at any time. When you come out of the stretch, take a moment to feel the sensation in your body. Can you recreate this feeling of length during your working day and your Yoga practice?

Experimentation

Last but not least, working with a partner can be a joyous way to bring fun and spontaneity into a practice session. New and beneficial partnerwork scenarios often arise out of this kind of playfulness. When I practice with a close friend, we often discover new ways to access tight areas of the body through openminded experimentation. Giving our imaginations a little freedom is a great way to bring lightness into both our movements and minds.

Partnerwork scenarios come as a solution to problems, difficulties or limitations. I’ll often ask a friend for help in getting more efficient leverage in an advanced asana, or to spot me when attempting a pose where I might otherwise fall on my first attempt. Or we may start with a paired stretch and find that we improvise to accommodate one person’s physical limitation or flexibility, creating something completely new.

Often, very flexible areas of the body are surrounded by immobile areas. It may be difficult to begin to move the rigid parts of the body, because we will naturally move from where we are already flexible. A partner stretch may help to stabilize a flexible region, so we can explore a tighter one.

Ask yourself where you feel restriction in difficult postures and work with your partner to devise ways to access those areas. (You can draw on adjustments that you have found particularly helpful in Yoga class.) Experimenting involves communicating with your partner. For example, you might say, “I feel like my shoulders are collapsing in this backbend. Could you help by lifting under the shoulder blades?” As your partner makes the adjustment, keep the dialogue going: “If you move your hands lower (or higher) it will give me more support,” or, “That’s too much (or too little) pressure.” These kinds of statements can clarify how you help and are helped by your partner.

This article originally appeared in Yoga Journal magazine, March/April 1991. Photographs by Randy Dean. © 2023 by Donna Farhi.

This bonus Feature is the last article in The Art of Asana series.

None of this material has been offered publicly for free before.

We hope you have enjoyed them. And if you've found value in them, please share.

share this

Related Posts