May 29

by Donna Farhi

This challenging posture requires us to temper our flexibility with strength, stamina, and spinal integrity.

Dear Reader

Please keep in mind that the images in this column were scanned from original archived articles and the quality might sometimes vary.

Benefits

Contraindications

Like many other people, I began Hatha Yoga with the idea that its purpose was to make the practitioner sublimely flexible. At age 16 this task wasn’t too difficult; indeed, after just a few months of daily practice I was touching my head to my knees and performing other such feats that have become impressive in our stiff society. Dance training only encouraged this focus, and well into my mid-20s I continued to stretch my limbs to an absolute extreme. Hypermobility soon turned into niggling problems with knees and ankles, sciatica, acute lower back and neck pain, and finally chronic back pain; it seemed that I was literally falling apart. Flexibility without strength had led me to a state of disintegration.

In fact, Hatha Yoga was not developed with flexibility as its chief goal. Flexibility was simply one sign of health; strength, stamina, and purity of mind and body were also cultivated to allow the aspirant to pursue the arduous task of sitting for long periods of meditation. Today, Hatha Yoga still cultivates these qualities, although what many practitioners are preparing for is not the meditation cushion, but the rigors of sitting in front of a computer or coping with the unrelenting stress modern

Like many other people, I began Hatha Yoga with the idea that its purpose was to make the practitioner sublimely flexible. At age 16 this task wasn’t too difficult; indeed, after just a few months of daily practice I was touching my head to my knees and performing other such feats that have become impressive in our stiff society. Dance training only encouraged this focus, and well into my mid-20s I continued to stretch my limbs to an absolute extreme. Hypermobility soon turned into niggling problems with knees and ankles, sciatica, acute lower back and neck pain, and finally chronic back pain; it seemed that I was literally falling apart. Flexibility without strength had led me to a state of disintegration.

In fact, Hatha Yoga was not developed with flexibility as its chief goal. Flexibility was simply one sign of health; strength, stamina, and purity of mind and body were also cultivated to allow the aspirant to pursue the arduous task of sitting for long periods of meditation. Today, Hatha Yoga still cultivates these qualities, although what many

Like many other people, I began Hatha Yoga with the idea that its purpose was to make the practitioner sublimely flexible. At age 16 this task wasn’t too difficult; indeed, after just a few months of daily practice I was touching my head to my knees and performing other such feats that have become impressive in our stiff society. Dance training only encouraged this focus, and well into my mid-20s I continued to stretch my limbs to an absolute extreme. Hypermobility soon turned into niggling problems with knees and ankles, sciatica, acute lower back and neck pain, and finally chronic back pain; it seemed that I was literally falling apart. Flexibility without strength had led me to a state of disintegration.

In fact, Hatha Yoga was not developed with flexibility as its chief goal. Flexibility was simply one sign of health; strength, stamina, and purity of mind and body were also cultivated to allow the aspirant to pursue the arduous task of sitting for long periods of meditation. Today, Hatha Yoga still cultivates these qualities, although what many practitioners are preparing for is not the meditation cushion, but the rigors of sitting in front of a computer or coping with the unrelenting stress modern life puts on our nervous systems.

life puts on our nervous systems.

practitioners are preparing for is not the meditation cushion, but the rigors of sitting in front of a computer or coping with the unrelenting stress modern life puts on our nervous systems.

In fact, Hatha Yoga was not developed with flexibility as its chief goal. Flexibility was simply one sign of health; strength, stamina, and purity of mind and body were also cultivated to allow the aspirant to pursue the arduous task of sitting for long periods of meditation. Today, Hatha Yoga still cultivates these qualities, although what many practitioners are preparing for is not the meditation cushion, but the rigors of sitting in front of a computer or coping with the unrelenting stress modern life puts on our nervous systems.

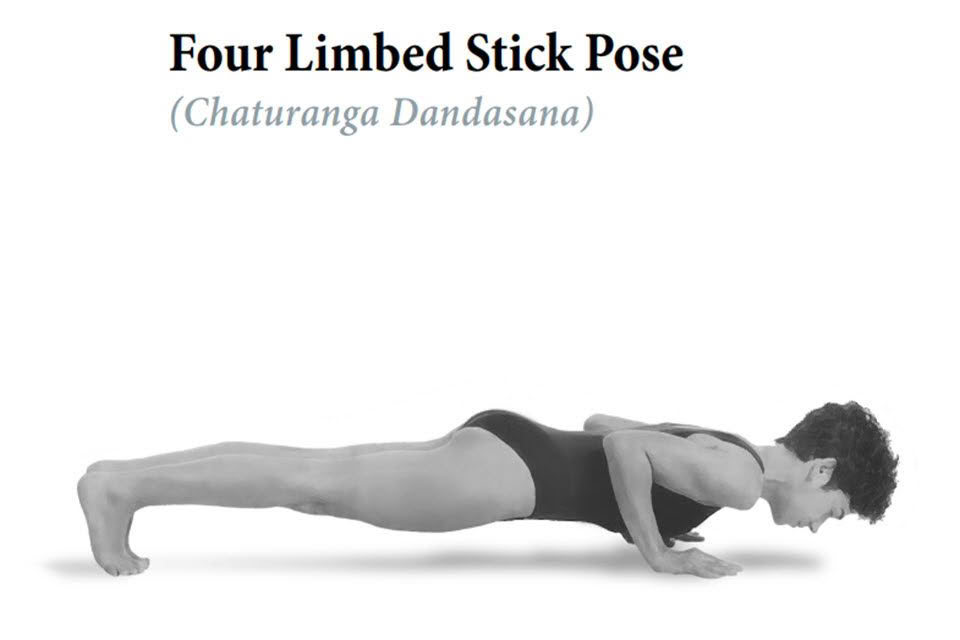

Four-Limbed Stick Pose (Chaturanga Dandasana) resoundingly contradicts the popular notion that Yoga equals contortionism. Rather, this asana is about keeping everything in one piece: The hands and feet touch the ground while the body is suspended above the ground in one unit, as in the calisthenic push-up. It’s not usually a popular pose for beginners because it requires a level of upper body and arm strength that is lacking in the average sedentary citizen. But the strength required to do Chaturanga Dandasana is not nearly as important as the ability to integrate and organize separate elements of the body so they function cooperatively.

The word ‘integrity’ comes from the Latin integrare, which means to renew or restore. Physical integrity is the renewal or restoration of the body’s original wholeness. This wholeness implies a coordination of movements, a communication between structures such as the legs and the spine. It also implies a balance of strength, flexibility, and relaxation that brings about a perfect tension between these three qualities. When this perfect tension is lacking, we experience ourselves as disjointed or simply ‘spaced out’.

Perhaps the reason Four-Limbed Stick Pose frustrates so many newcomers to Yoga is that it can only be done if there is a strong cohesive force running through the whole body from head to toe and from front to back. The force running through the spinal column should be even and unbroken. (Imagine balancing a stick across your finger: think how easy it would be to balance a straight stick of uniform diameter and how difficult to balance an irregular piece of wood.) The integrating force through the length of the torso derives primarily from the support of the arms and the driving power of the legs reaching back. It also comes from the relationship between the soft frontal body (the throat, lungs, abdominal organs) and the firm back body (the spinal column, rib cage and pelvic girdle).

One of the ways we establish the appropriate relationship between the front and back bodies is by allowing certain underlying muscle reflexes to work for us rather than against us. Reflexes are a force contributing to postural tone, the background activity of muscles beneath the level of voluntary muscle contraction. The most helpful reflex in Chaturanga Dandasana is the sucking or swallowing reflex, which develops while an infant breastfeeds. When the throat moves back in a swallowing motion, it initiates a reflexive wave down through the soft organs and the frontal muscles of the body, which moves the lungs, abdominal muscles, and organs back against the spine. When this action occurs, it’s much easier to keep the spine unified, because, instead of the belly and throat hanging heavily away from the spine, both the front and back of the body are equally supported.

Preparatory Stance

In the following preliminary exercise, we explore how this reflex can integrate our bodies to prepare us for practicing Chaturanga Dandasana.

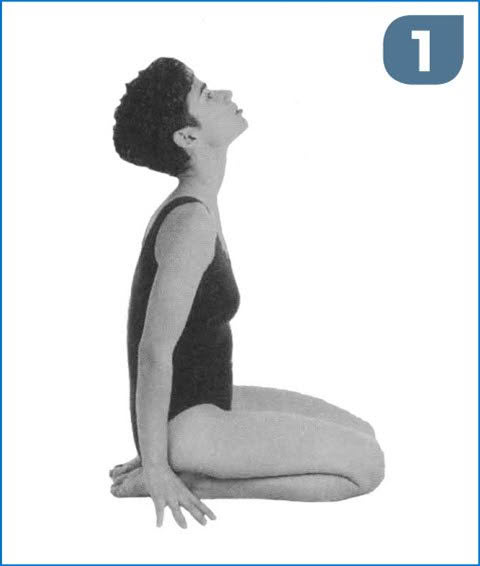

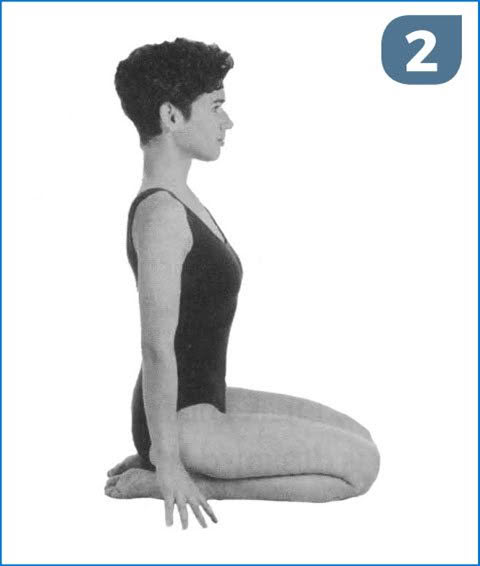

Kneel or sit cross-legged on a blanket. Begin by sitting upright with the crown of the head balanced over the center of the abdomen. Then lift your chin and let the throat hang forward (Fig. 1). Did you notice that your abdomen automatically popped out? Now draw the front of the throat gently back as if swallowing or sucking, slightly tucking the chin (Fig. 2).

You may even want to swallow or smack the lips together to stimulate the reflex. Did you notice that the abdomen automatically moved in and back against the spine? Go back and forth between these two positions, projecting the throat forward and then drawing it back. Sense how the entire frontal body, including the soft internal organs, becomes lax as the throat projects forward and how an overall sense of tonus comes when the throat is drawn gently back. When you’re ready, continue on to the next exercise.

Beginner’s Practice

Chaturanga Dandasana is usually performed following Downward-Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanasana). Many common errors in Chaturanga Dandasana are simply bad habits carried over from Adho Mukha Svanasana. The following exercise focuses your attention on the correct placement of the hands and arms. Maintain this awareness as you progress into Chaturanga Dandasana.

Kneel on all fours and place your hands in front of you, shoulder-width apart on a hard surface. Carefully position your wrists so the flexion creases across the top of the wrist are parallel with the wall in front of you. Without turning the wrists in or out, extend the fingers so they radiate in all directions. This action will help distribute the weight of the body over a broader base. Now check that you are pressing into the inner wrist as much as the outer wrist. Rocking onto the outsides of the wrists causes wrist pain and injury in these weight-bearing poses. Finally, lift the forearms up so the base of the palm almost lifts off the floor. This action will allow the weight of the body to be carried by the front portion of the palm and fingers rather than solely by the base of the wrist. After a minute, sit back into Child’s Pose, completely resting the arms.

Never practice poses such as Chaturanga Dandasana on a soft carpet or a surface like sand where the wrist will hyperextend below the level of the fingers. This hyperextension can cause immediate discomfort and may contribute in the long term to serious conditions such as carpal tunnel syndrome, in which pressure on the median nerve in the wrist area causes pain, tingling, and muscular weakness.

Variation

Now kneel on all fours again, placing the hands carefully as just described. Then sit back so the buttocks rest lightly on the heels, with the toes turned under. Bring the head and chest close to the floor and draw the front of the throat back toward the neck as you did in the preliminary exercise. This action will increase the muscle tone throughout the front of the body, especially along the abdominal muscles. Maintaining this frontal support, shift the chest forward through the arms, dropping the chest toward the floor before the abdomen (Fig. 3). This point is crucial, because if the abdomen drops toward the floor first, your upper back will be drawn into an arch. It will then be very difficult to lower the chest to the floor without collapsing the lumbar spine.

As soon as the torso begins to move forward, bend the elbows, keeping them close to the ribs. Imagine the torso and elbows as two trains passing each other in opposite directions. As the head comes forward in front of the hands, continue in a circular motion to push up and back to the starting position on all fours. The pelvis and abdomen should lead in the ascent. Maintain a sense of connection between the front and back of the body as you come up, to prevent yourself from collapsing and breaking the strong line of force through the central axis of the torso.

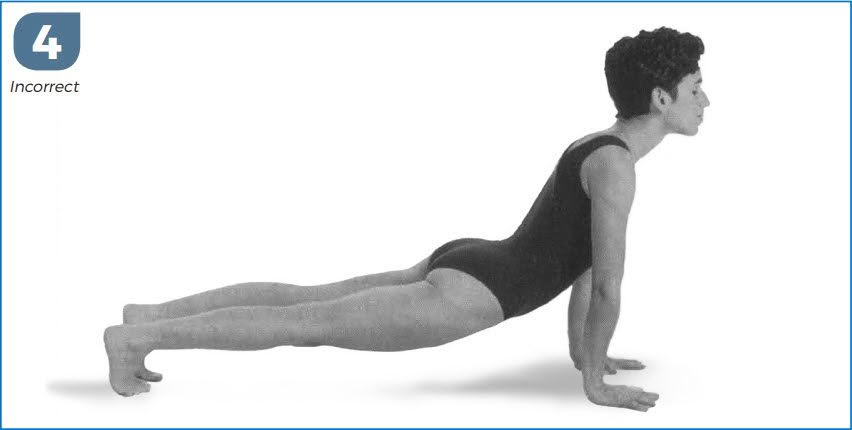

One of the most common errors in Chaturanga Dandasana is bringing the chest and head all the way forward over straight arms. Because lowering yourself from this position is so much more work for the arms, you will invariably try to come down by arching the upper back and lowering the abdomen to the floor first (Fig. 4). You can avoid this problem by synchronizing the forward movement of the chest with the bending of the elbows.

Now try the pose again, this time focusing your attention on your hands and arms. Check that the elbows do not splay out to the sides as you come forward, an action that will cause the shoulders to turn inward and the weight to fall heavily onto the outer wrist. As you shift your chest through the arms, be especially careful not to lift the front portion of the palm and drop into the base of the wrist. By keeping the pressure on the front portion of the palm and fingers, you not only avoid straining the wrists but activate the shoulders and upper chest.

A little attention at this early stage of practice will go a long way toward preventing painful wrist injuries. Just as practicing Dog Pose prepares you for Chaturanga Dandasana, practicing Chaturanga Dandasana with careful alignment in the hands will prepare you for the more advanced arm balances such as Crane Pose (Bakasana). What you learn in the simpler poses is naturally incorporated into more complex positions.

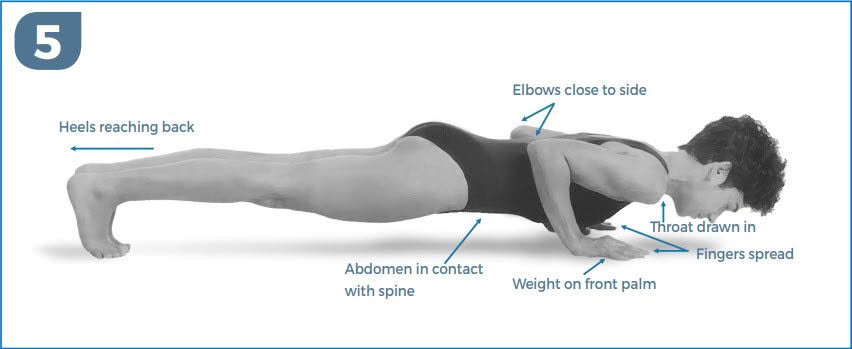

Advanced Practice

Begin as in the variation, except this time, as you bring the head past the hands, lift the knees off the floor (Fig. 5). Slide the feet backward until the legs are completely straight, extending strongly back through the heels. Breathe evenly, reaching out through the head and heels. To come out of the pose, bring the chest even farther through the arms and in a circular motion lift up and back into Adho Mukha Svanasana.

Just as it is important for the health of the spine not to come down into this asana with the back collapsed, it is equally important that you come out of the posture using the arms, chest, and abdominal muscles rather than the muscles along the back of the spine. Be sure to keep the back straight. The back will feel the least strain if you activate the front of the body so the throat and abdominal muscles feel connected to the front of the spine. If you find that you do not have the arm strength to come up with the legs straight, touch the knees to the floor and make an honest attempt to come out with integrity in the spine. You will progress very quickly, gaining strength and coordination, if you work from a place of spinal integrity. Conversely, you will stay weak in the arms and upper body, as well as straining the back, if you insist on arching the spine to come out of the pose.

In the final variation of Chaturanga Dandasana, come forward from Downward-Facing Dog Pose (Adho Mukha Svanasana) with straight legs. Maintain a strong reach back through the heels throughout your descent so that the lumbar spine elongates. Move the elbows back toward the feet and in toward the ribs. When you are able to keep the torso as one unit, the driving force will move so clearly from the hands to the feet and from the crown of the head to the tailbone that an unexpected lightness will fill the body. This lightness is a good indication that you have indeed fused the many parts of yourself into an integrated whole.

Achieving this kind of body integration takes time and may be more difficult than the more measurable goal of flexibility. Taking something apart (as many a budding mechanic has discovered) is often easier than putting it back together again. For students with very loose ligaments and highly flexible bodies, poses like Chaturanga Dandasana can be as much a psychological testing ground as a physical challenge.

It took at least a year of practicing before I could lower myself into Chaturanga Dandasana without collapsing. I clearly remember the moment as a stepping-stone. Many other things seemed to ‘come together’ in my life after that, as if the cohesion between my tissues was bringing about a psychological sturdiness.

Necessary limitations and constraints balance mobility and freedom, much as the molecular force between particles acts to unite them into a whole. The interplay between flexibility and integrity and the ongoing regulation of each by the other is part of the process of regaining wholeness, which we call Yoga. The lessons we learn from the challenging struggle of bringing these diametric qualities into balance are what we will carry with us when we step off the yoga mat.

This article originally appeared in Yoga International magazine, May/June 1993. Photographs by Fred Stimpson. © 2023 Donna Farhi.

New Insights

The new insights of Chaturanga Dandasana have been incorporated into the next feature Vasisthasana Vinyasana.

To be notified of the next article, please scroll down and join our Newsletter.

And if you've found this article valuable, please share it.

share this

Related Posts

As I have been drawn, in my own practice, more deeply into the details of the body and the revelation of “integrity “, I so appreciate these offerings – so clear and beautiful. Thank you!

You’re very welcome Rivkah.