December 1

by Donna Farhi

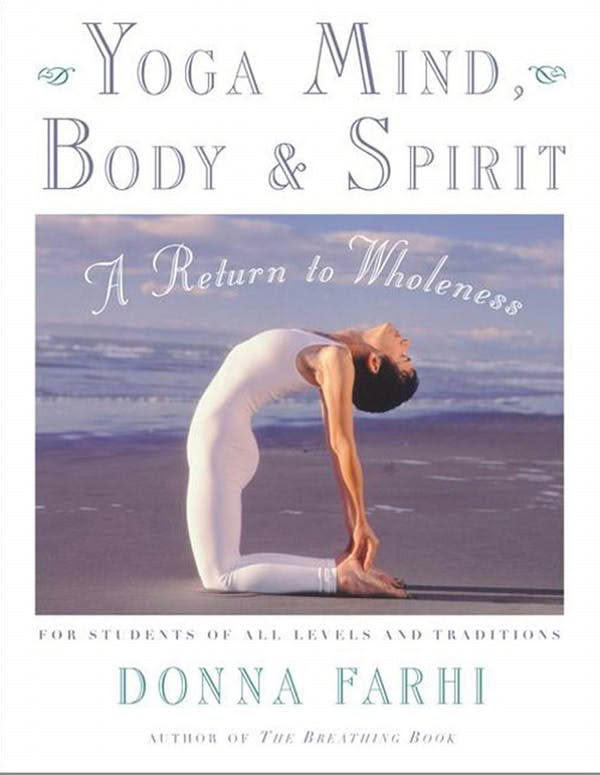

An extract from Yoga Mind Body & Spirit

(Macmillan Publishing, 2000)

Given the central importance of the yamas and niyamas, one might wonder why it would be necessary to practice the other limbs of yoga. Would it not be enough to be compassionate, truthful, and content? Why would it be important to take the time to stretch our backs or listen to our breath? If not for the tremendous importance of grounding spirituality in the body, it's unlikely that the great sages would have listed asana practice as the second limb. This is why I have chosen to focus in such detail on this dimension of practice. What is asana practice all about?

The word asana is usually translated as “pose” or “posture,” but it's more literal meaning is “comfortable seat.” Through their observations of nature, the yogis discovered a vast repertoire of energetic expressions, each of which had not only a strong physical effect on the body but also a concomitant psychological effect. Each movement demands that we own some aspect of our consciousness and use ourselves in a new way. The vast diversity of asanas is no accident, for through exploring both familiar and unfamiliar postures we are also expanding our consciousness, so that regardless of the situation or form we find ourselves in, we can remain “comfortably seated” in our center. Intrinsic to this practice is the uncompromising belief that every aspect of the body is pervaded by consciousness. Asana practice is a way to develop this interior awareness.

While the dancer’s or athlete’s internal impulses result in movement that takes him into space, in asana practice our internal impulses are contained inside the dynamic form of the posture. When you witness a yoga practitioner skilled in this dynamic internal dance, you have the sense that the body is in continuous subtle motion. What distinguishes an asana from a stretch or calisthenic exercise is that in practice we focus our minds attention completely in the body so that what we can move as a unified whole and so we can perceive what the body has to tell us. We don't do something to the body, we become the body. In the West we really do this. We watch TV while we stretch; we read a book while we climb the StairMaster; we think about our problems while we take a walk, all the time living a short distance from the body. So asana a practice is a reunion between the usually separated body-mind.

Apart from the vibrant health, flexibility, and stamina this unified body-mind brings us, living in the body is also an integral aspect of spiritual space. The most tangible way that we can know what it means to be compassionate or not grasping is directly through the cellular experience of the body. The most direct way that we can learn what it means to let go is through the body. When we have a self-destructive addiction—the impulse to overeat or to take drugs—this happens through the entrenchment of neurological and physiological patterns in our bodies. And on a more basic level, it's hard to feel focused and purposeful when our bodies are full of aches and pains or burdened with illness and disease.

While I have given the practice of asanas great emphasis in this book, it is not because the perfection of the body or of yoga postures is the goal of yoga practice. This down-to-earth, flesh-and-bones practice is simply one of the most direct and expedient ways to meet yourself. It is a good place to begin. Whether you meet yourself through standing on your feet or standing on your head is irrelevant. It's important, therefore, not to make the mistake of thinking that the perfection of the yoga asana is the goal, or that you'll be good at yoga only once you've mastered the more difficult postures. The asanas are useful maps to explore yourself, but they are not the territory. The goal of asana practice is to live in your body and to learn to perceive clearly through it. If you can master the Four Noble Acts, as I like to call them, of sitting, standing, walking, and lying down with ease, you will have mastered the basics of living an embodied spiritual life. This book gives you the tools to do this and to go further if you wish.

The emphasis on asana practice is also specific to the age we live in, for we live in a time of extreme disassociation from bodily experience. When we are not any our bodies, we are disassociated from our instincts, intuitions, feelings and insights, and it becomes possible to disassociate ourselves from other people’s feelings, and other peoples suffering. The insidious ways in which we become numb to our bodily experience and the feelings and perceptions that arise from them leave us powerless to know who we are, what we believe, and what kind of world we wish to create. If we do not know when we are breathing in and when we are breathing out, when we are unable to perceive gross levels of tension, how then can we possibly know how to create a balanced world? Every violent impulse begins in a body filled with tension; every failure to reach out to someone in need begins in a body that has forgotten how to feel. There has never been a back problem or a mental problem but didn't have a body attached to it. This limb of yoga practice reattaches us to our body. In re attaching ourselves to our bodies we reattach ourselves to the responsibility of living a life guided by the undeniable wisdom of our body.

Practicing with joyfulness

When we begin practice, we may feel far from happy within ourselves. In fact, even the semblance of happiness may seem as remote to us as winning the lottery. We may feel utterly confused, buried in self-destructive habits, and encumbered by difficulties, whether emotional, physical, or material, that appear insurmountable. Our bodies may feel as stiff and knotted as an old tree, and our minds s jumble of worries and neurosis. Platitudes about the peace and happiness available to us right now sound empty in the face of our very real pain. Most of us begin like this, and even those who feel some sense of inner balance often find that underneath the thin veneer of appearance, there is much work to be done.

How do we go about doing this work without becoming discouraged by the enormity of the task? Unless we can find a way to practice with joyfulness, working without difficulties rather than against them, practice will be an experience of frustration and disappointment. Unless we can find a way to enjoy what we're doing right now, yoga practice will become a negative time, and ultimately we’ll develop a strong resistance even to stepping onto the mat.

A story may help you to understand what I mean. Many years ago, I moved into a derelict house. The back door was nailed shut and had not been opened for fifteen years; once pried open it revealed a six-foot wall of seemingly in penetrable blackberry bushes, vines, and crabgrass. I wanted a garden. For many months I looked in despair through the window of the back door. The task seemed too large and too difficult. Then I decided upon a strategy that my mind could grasp. I decided that I would divide the project into four-foot increments. Every week I would clear a four-foot patch of garden. The backyard was sixty-five feet long! As I would begin to dig and root, cutting and pulling my tiny patch, I resolved that I would focus my attention only on the four-foot patch. I would not even look at the other sixty-one feet of the garden left to clear. Within minutes of beginning, I would become completely absorbed in the insects, the tiny plants uncovered, and the pleasure of digging my hands into the brown earth. Each four-foot patch took about three hours because the crabgrass had to be dug out completely and the earth was rock hard. But three hours a week was an easily manageable commitment. When I finished with the patch, I would step back and admire my good work, never allowing myself to consider the chaotic mess left remaining. How wonderful it looked! Each four-foot patch was a unique wonder. Pathways buried two feet under emerged. A lawn mower, enveloped by grass (proof of the law of karma), was discovered. Not only was the task challenging, it became an adventure, and I eagerly anticipated what I might find each week. Within a year I had a beautiful lawn, an herb garden, and a patch of flowers to enjoy. But, more important, I enjoyed the process of transporting transforming an inhospitable patch of ground into an urban paradise.

When you begin to practice, you may feel very bound in your body and mind, not unlike the densely woven crabgrass of my garden. You can choose to fight with yourself, pulling and tugging on yourself as a way to force your own metamorphosis. If you've ever encountered a weed with deep roots, you know the futility of pulling at the stem knowing full well some digging is in order! There's a moment when you can cheerfully accept the task and set to it with full vigor, or turn sour and miserable in the face of such work. There's a moment when you can resign yourself to the patient work ahead or give in to the impulse to pull on the stem before the ground has been dug deep enough. The first step is accepting that some deep work needs to be done and then deciding to make this a positive, uplifting experience.

In yoga practice you can do this by dividing your experience into incremental breaths and taking care of only that which arises in one breath cycle and no more. In this way almost any difficulty becomes manageable. Rather than focusing on how much further you wish you could go, or comparing your meager efforts with those of someone who is more adept, you can choose to focus on what you are accomplishing in each breath. Maybe today you open your hip five millimeters farther, or you manage to sit comfortably in meditation for the first time. As you investigate the tightness around your hip you discover ways to release it; as you sit for five more minutes you discover that those “urgent” matters are really not so urgent. It is only through these tiny, slow, and progressive openings that deep, profound change occurs. It is your choice to take pleasure in these small awakenings or to disregard your efforts as insignificant in the face of how much further you have to go. You can choose to have a sense of humor about your dilemma or fester negativity. Whom would you like to garden with?

When we make a practice a joyful time, it is also much more likely that we are growing more deeply within our spiritual life. When we get hooked into striving toward where we think we should be and how far we ought to be able to go, in truth we are somewhere else all the time. We are in a fantasy, our ideas, our concepts, and our judgments. There's not much room in there to perceive and appreciate what's actually happening. Even when we feel pain, even when we face great difficulty, we can take refuge in our practice. There will inevitably be times when progress is slow, when injury or illness or life circumstances limit our ability to the outward forms. But this doesn't limit our ability to plumb the depths of our inner life.

Each day as you step onto your mat, make a decision to enjoy just where you are right now. Take a few moments, too, to contemplate how fortunate you are to be practicing this wonderful art. A casual glance at the morning paper is proof enough of the vast suffering, poverty, violence, and homelessness that is the lot of so many human beings. If you are standing on a yoga mat and have the time to practice even fifteen minutes, you are a fortunate person. If you have a yoga teacher, you have an invaluable gift and life tool available to very few people. In the spirit of this gratefulness, let your practice begin.

share this

Related Posts